This article was featured in New York’s One Great Story newsletter. Sign up here.

Experts were sure that the 20th century would make us stupid. Never before had culture and technology reshaped daily life so quickly, and every new invention brought with it a panic over the damage it was surely causing to our fragile, defenseless brains. Lightbulbs, radio, comic books, movies, TV, rock and roll, video games, calculators, pornography on demand, dial-up internet, the Joel Schumacher Batmans — all of these things, we were plausibly warned, would turn us into drooling idiots.

The test results told a different story. In the 1930s, in the U.S. and across much of the developed world, IQ scores started creeping upward — and they kept on going, rising on average by roughly three points per decade. These gains accumulated such that even an unexceptional bozo from the turn of the millennium would, on paper, look like a genius compared to his Depression-era ancestors. This phenomenon came to be known as the Flynn effect, after the late James Flynn, the social scientist who noticed it in the 1980s.

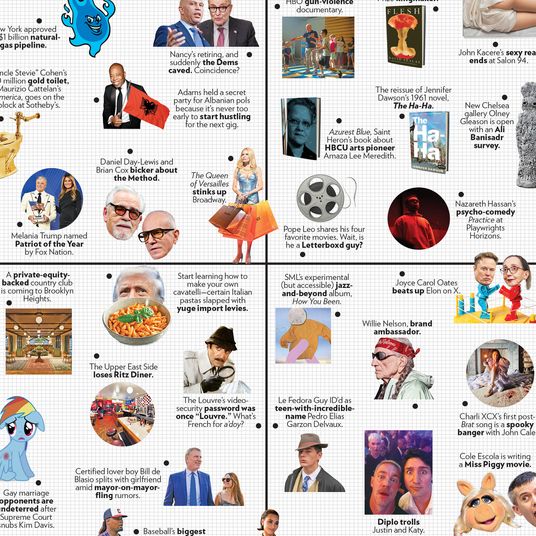

In This Issue

Because these leaps appeared over just a few generations, Flynn ruled out genetics as their cause. Evolutionary change takes hundreds of thousands of years, and the humans of 1900 and 2000 were running on the same basic mental hardware. Instead, he posited that there had been a kind of software update, uploaded to the collective mind by modern life itself.