MAYPEARL, Texas — The new police chief quickly impressed the small Texas community he’d sworn to protect. He started a Christmas charity event. He checked on elderly neighbors.

He seemed especially good, residents noted, with troubled teenagers.

The people of Maypearl trusted Police Chief Kevin Coffey.

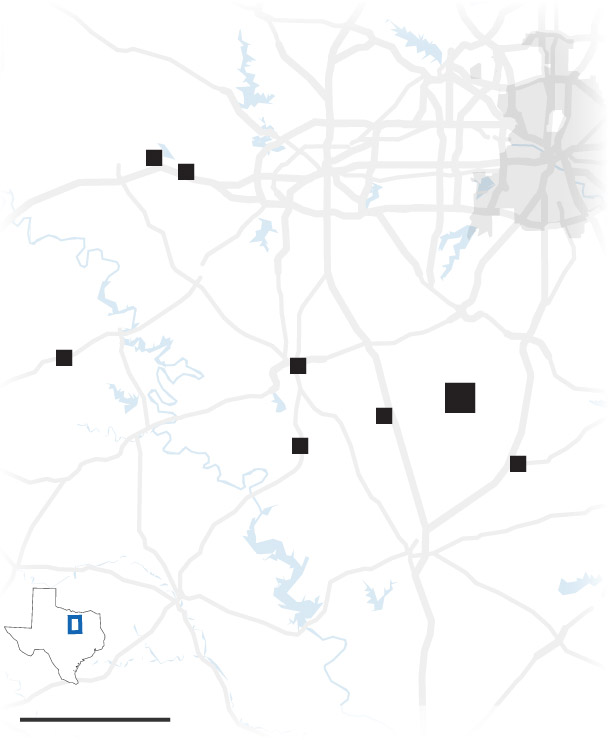

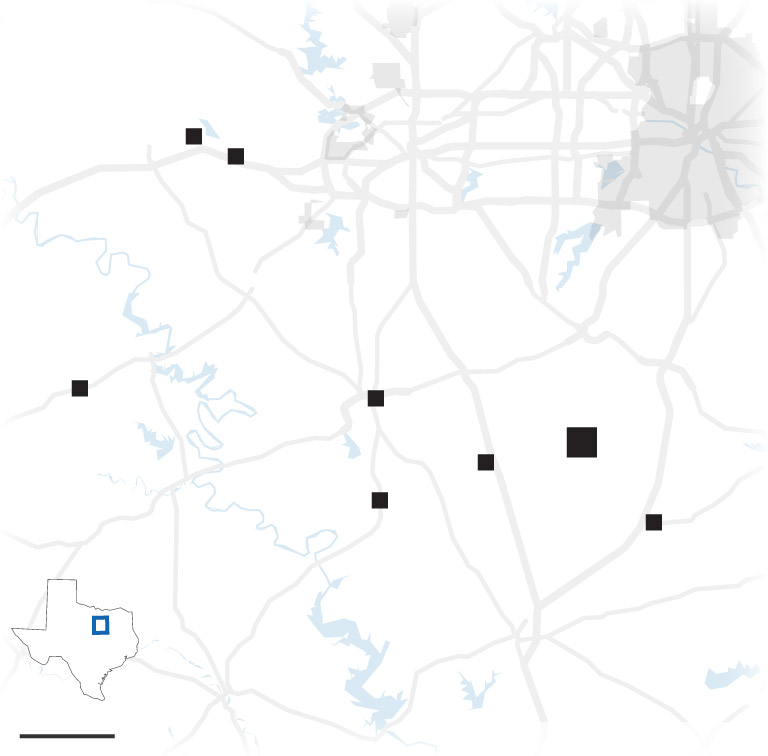

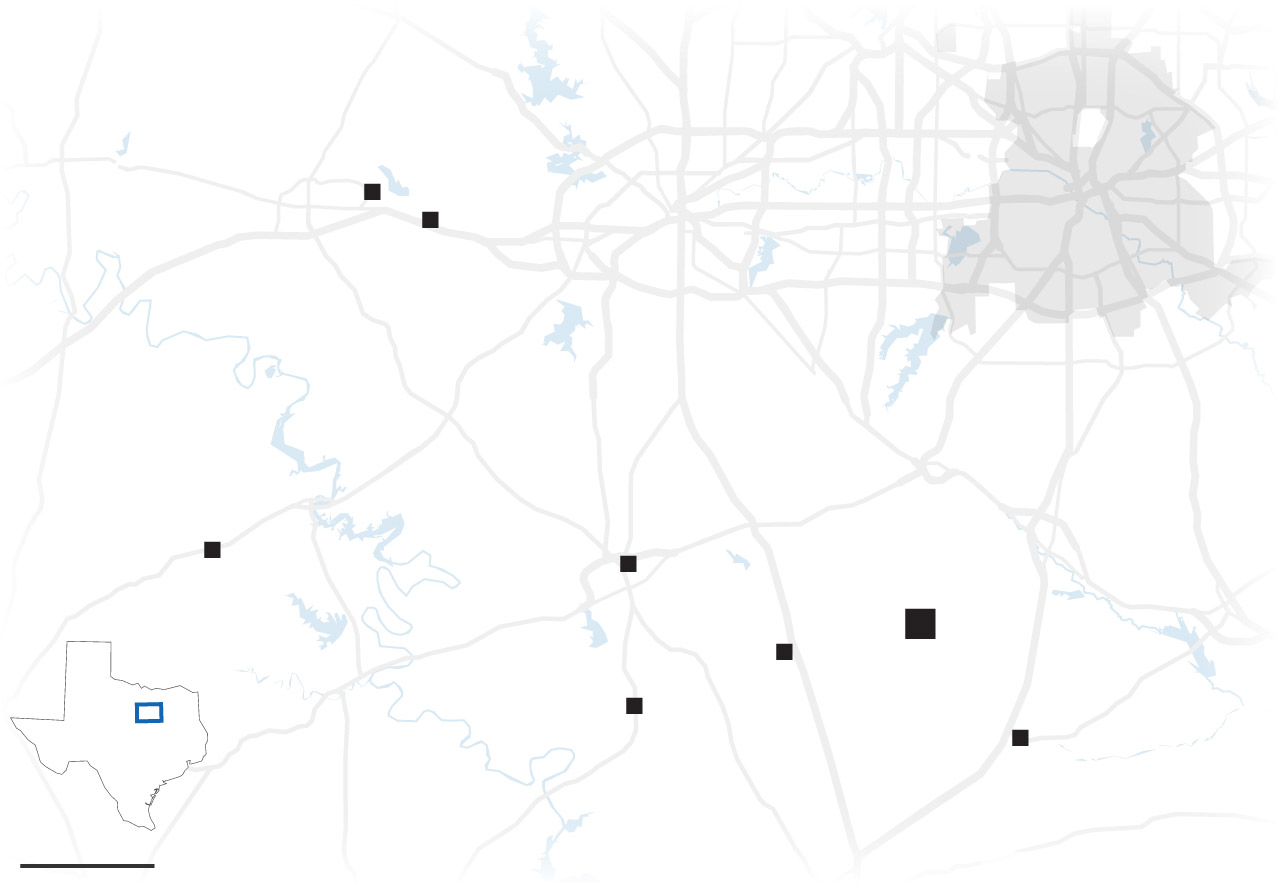

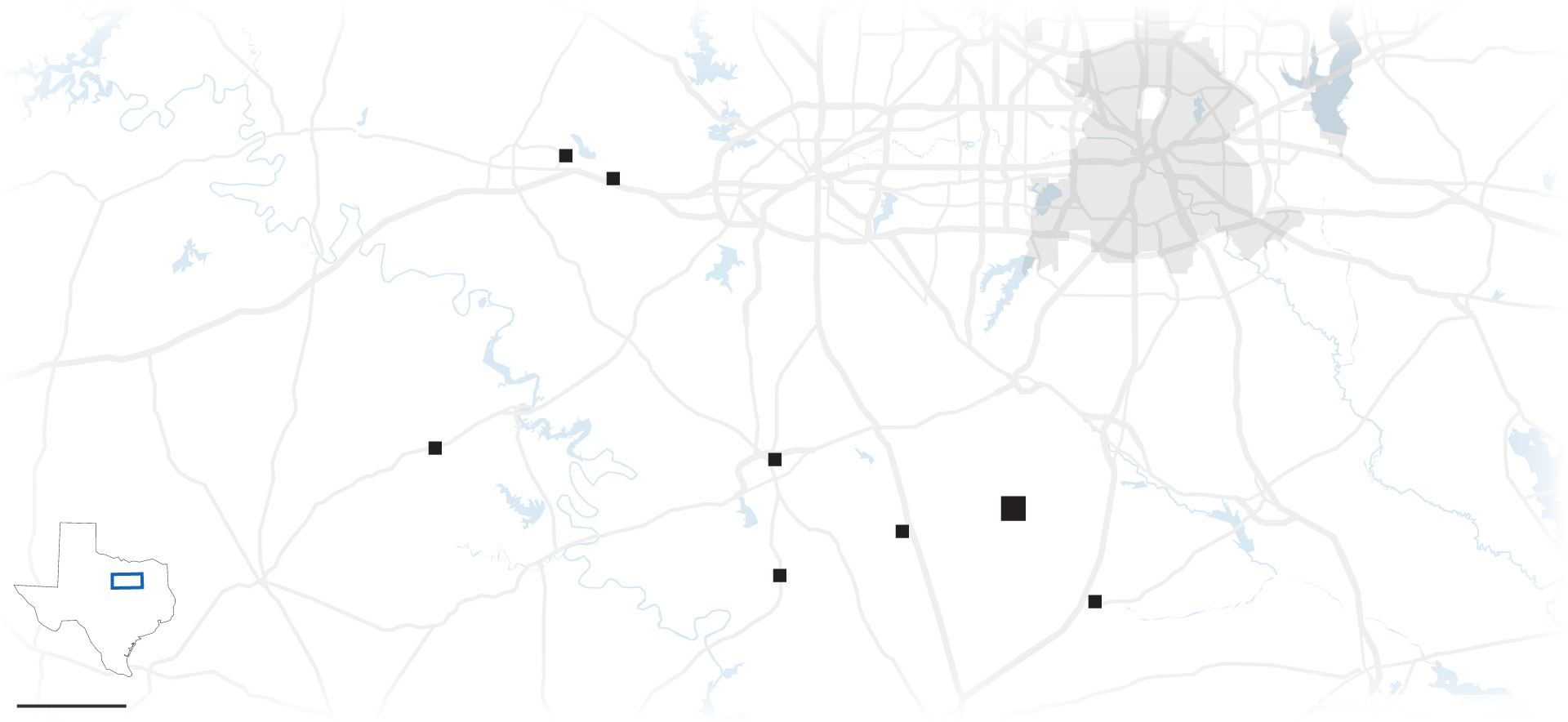

Few were aware that Maypearl was the eighth law enforcement agency that Coffey had worked at in 11 years. Fewer knew that there was a trail of accusations and secrets in his past. And none could have predicted the destruction he would wreak in their town.

The kids would eventually call him The Creeper. The adults would denounce him as a monster. The prosecutors who put him away for child sexual abuse would describe him as a master manipulator “who groomed the community.”

Unmute the videos to hear how a predatory police chief upended lives across Texas

But Coffey, sitting behind a glass partition in a state prison, would struggle to describe himself — and how he got away with exploiting his power for so long.

The ‘Voice of Maypearl’

Here in Maypearl, there are several unshakable truths. Friday nights are best spent at the high school, rooting for the Panthers. The most interesting gossip (and cheapest beer) is found at the Busy Bee Cafe. And never, ever mess with Geneva Zoll.

Known to everyone as just Geneva, the 49-year-old farmer and grandmother is widely seen as the unofficial mayor of Maypearl.

In this city of less than 1,000 south of Dallas, Geneva could always be found at the holiday and homecoming parades, giving out hugs. She ran a Facebook group called “Voice of Maypearl.” She offered blunt, sometimes profanity-laced advice while she poured coffee at the Busy Bee or the Rock’n R diner on Main Street. At night, when the diner turned into a bar, Geneva’s husband, Zach, could be seen singing onstage in his denim overalls, a beer in each hand.

“Everybody in Maypearl knows everybody and knows their business — whether you want them to or not.”

Whenever there was a problem in Maypearl, people found Geneva. She’d once led an effort to get rid of a police officer who was accused of harassing residents, constantly pulling them over for no good reason. After Geneva helped get that cop off the force, she thought the town’s problem with its police department was over.

But then, one day in 2015, a 16-year-old girl approached Geneva at the Rock’n R.

The girl said the worst officer was still in Maypearl. The proof, she said, was on her broken cellphone. If Geneva could get the phone fixed, she would find messages the teen had been receiving from someone the community revered — its police chief, Kevin Coffey.

‘Disgusting’ texts

After Geneva shelled out $150 to repair the cellphone, she started reading message after message from the chief.

“I wanted him gone. It was horrifying to know that someone in charge of your town, supposed to be protecting these kids, is actually doing this.”

The 16-year-old was named Alissa. Her parents owned the Rock’n R. She’d grown up around Maypearl — and knew that it was no small thing to accuse a chief of sexual misconduct.

Her encounters with Coffey had started when she was around 14. After getting in trouble for underage drinking, she said, her punishment had been an act of community service: cleaning City Hall.

How this story was reported

Coffey, who was more than three decades older than her, came by as she was working. Alissa said he told her that her butt looked good in the jeans she was wearing. Then he instructed the teen to dust his office.

The chief began messaging the high-schooler on Facebook and Snapchat. Alissa would later report that Coffey flashed his police cruiser lights into her window. He frequently touched her, she said, rubbing her arm, running his hand through her hair. He took photos of her in his patrol car. He sent her a picture of his handcuffs, saying, “One of these days.”

Geneva wanted Coffey to be fired and arrested. But who, she wondered, would she report him to? He had the top job at the police department. He was cozy with the city’s mayor. So Geneva called and texted the sheriff of Ellis County, where Maypearl is located.

Surely, Geneva thought, the sheriff would take action against a police chief sending sexual messages to a child.

But Sheriff Johnny Brown told her that he couldn’t help.

Geneva couldn’t let it go. While trying to persuade Alissa’s family to file a report, she looked for someone in law enforcement who would do something. Eventually, Ellis County prosecutors learned of the accusations and formally launched an investigation with the Texas Rangers, a state law enforcement agency. For five weeks after Geneva complained, Coffey remained in power.

Brown, who is no longer sheriff, defended his actions to The Washington Post, saying that without cooperation from the girl and her family, he had no case. But the district attorney at the time, Patrick Wilson, was furious.

“If someone tells you that there’s a police chief who may be having inappropriate sexual relationships with minors ... you don’t sit on that information.”

A chief’s power

Geneva wasn’t the first adult Alissa had confided in about Coffey’s behavior. About a year earlier, the teen had complained to her mom. At first, her mom said, she encouraged her daughter to ignore Coffey, rather than risk reporting the chief in such a small town: “We kept thinking, this is gonna stop.”

“My parents were just like, ‘Leave it alone.’ They didn’t want it to affect the small business they were running. So I kept my mouth shut.”

Later, when Alissa’s mom learned from Geneva that Coffey was still targeting her daughter, she finally realized: The chief wasn’t going to stop, unless someone stopped him.

Speaking out against law enforcement is especially difficult in small towns, where cops are deeply embedded in the communities they serve. For the residents, there are often fewer avenues to lodge misconduct complaints and less protection from retaliation.

Like Maypearl, nearly half of all local police departments across America have fewer than 10 full-time sworn officers. Their chiefs wield tremendous power.

A Post investigation identified 47 heads of law enforcement agencies who were charged with crimes involving child sexual abuse from 2005 through 2022. Three-quarters of them worked in departments with less than 10 cops.

“When it comes to the police, people are just so scared to say anything. They’re so scared for their own safety, or to go to jail, or get a ticket or harassment from it.”

Coffey had spent years gaining the trust of Maypearl’s parents after getting hired there in 2010 as a patrol officer. He followed up with teens after car accidents. He quickly responded to reports of runaways.

But some high-schoolers, like Mallory Meyer, knew things weren’t quite right, even before Coffey got promoted to chief. He’d often message her friends. Once, Mallory said, she’d heard him encourage a teen girl to twerk on his police cruiser. By the time she saw Coffey with Alissa on his lap at the Rock’n R, where Mallory was a waitress, she had already been complaining to her father.

Her dad, James Meyer, went to Shannon Bachman, the man who was Maypearl’s police chief at the time. Bachman would later maintain in a court affidavit that James talked about an officer making girls uncomfortable but didn’t give specifics.

“Everybody said the same thing,” Coffey’s old boss told The Post. “Oh, he’s creepy.”

Bachman didn’t like Coffey, but said he never received complaints that warranted disciplining or firing the officer.

The harassment started, Mallory said, soon after her father spoke up.

Records show Coffey arrested James in his own home in May 2013 for open traffic violations from another town. Mallory’s dad told friends that police were following him and shining lights into the window of his house. James, who had struggled with his mental health, grew increasingly anxious.

After Coffey was promoted to chief that September, Mallory said she too was followed and pulled over by the Maypearl police.

“It felt like we were screaming and my dad was screaming and no one could hear us.”

James hired a lawyer, and eventually Mallory filed a lawsuit against Coffey, claiming that he had used his position to retaliate against her father and intimidate their family.

James Meyer did not live to see how the chief would be held accountable. He took his own life on June 13, 2015.

Within weeks, state investigators were closing in on Coffey, targeting him in a sting operation, then obtaining a warrant to search his home.

On July 22, Coffey was charged with sexually abusing a teenage girl.

Hired. Fired. Repeat.

In a town nearly an hour from Maypearl, a 29-year-old nurse saw the news about Coffey’s arrest. She immediately started praying. The next day, Angel Hilton called the Texas Rangers.

For almost 15 years, Angel had kept a secret.

When she was 14 and crammed into a pickup truck with a bunch of friends, a cop pulled the teens over. Back then, Coffey was working for the Grandview Police Department. The officer, more than twice her age, ordered Angel and her friends to step out and put their hands on his patrol car. Then, Angel said, he told her that her butt looked cute.

Coffey soon learned about Angel’s troubled home life and how she was often left alone or in the care of her grandfather.

“It got to be a routine,” she said. “He would drive by the apartment and flash his lights on the cop car. … And then I would meet him out on the side of the road and he would pick me up.”

“I thought, okay, he’s law enforcement. So nobody’s gonna touch me if I’m with him. Nobody’s gonna hurt me if I’m with him. He will protect me.”

During their rides together, Coffey listened attentively to the teen and told her how pretty she looked. “Those things,” Angel said, “made me feel loved.” But then, the touching began. After Coffey found her at a local ballpark one night, she would later testify, he penetrated her with his finger.

By that time, she thought that one day they could be “boyfriend and girlfriend.”

On her 15th birthday in April 2001, Coffey took her to the Olive Garden to celebrate. She said he gave her alcohol and brought her back to his home. He took photos of the teen beside his bed in her black boots and miniskirt. That night, she told investigators, the officer groped her breasts and stuck his hand up her skirt.

No one at the Grandview Police Department seemed to notice how much time Coffey was spending in his cruiser with a minor. But at Coffey’s next job, working for the Hudson Oaks Police Department, his supervisor, Brandon Mayberry, said he discovered Coffey was harassing a different teenage girl — and got him fired for it.

“I took his gun and his badge and I said, ‘You’re done,’” Mayberry remembered.

It didn’t matter. Before long, Coffey found another job at a nearby department. He kept being handed a badge and a gun, Mayberry said, even when he tried to warn agencies that Coffey wasn’t fit to be an officer. The more places Coffey worked at, the more complaints he racked up.

Coffey worked at 8 departments in 11 years and was repeatedly accused of misconduct

Coffey had even been accused of mistakenly shooting another officer while serving a warrant. The injured cop sued Coffey and his employer, records show, and eventually received a settlement.

It’s unclear what kind of digging Maypearl officials did before they hired Coffey. They told The Post they no longer had any of his employment records.

Three years after he started patrolling Maypearl’s streets in 2010, Coffey got promoted to chief.

In plain sight

The more state investigators looked into Coffey after his arrest in 2015, the more they unearthed. They interviewed Alissa, who'd come forward in Maypearl, and Angel, who'd called to report his past in Grandview. They searched Coffey’s home, office and a storage unit.

On social media, investigators learned, the chief had been calling himself “shadowdancer.” But to the prosecutors assigned to the case, it was clear that Coffey hadn’t been lurking in the shadows. He’d been grooming the community in plain sight.

“I would call him the perfect perverted predator,” said Grace Pandithurai, an Ellis County prosecutor.

On Coffey’s electronic devices, investigators found dozens of pictures of teenage girls that he’d been collecting for years. They found the photos of Angel. They found nude pictures of a teenage runaway.

They asked Angie Smith, a Maypearl city employee who sat across from the chief’s office, to help identify some of the girls. Then she made a startling discovery: Coffey had pictures of her teen daughter.

“All my kids called him The Creeper. And I didn’t even know they called him that.”

As news of the investigation spread through Maypearl in the summer of 2015, it seemed that everyone had a story about the chief that they hadn’t shared before. In the “Voice of Maypearl” Facebook group, Geneva found post after post about Coffey abusing his power.

Her neighbors, Geneva realized, weren’t just grappling with what Coffey had done, but with what most in the community had failed to do: speak up.

The chief on trial

On February 14, 2017, Coffey arrived on the third floor of the Ellis County Courthouse to face a jury. He’d pleaded not guilty to sexual assault of a child and indecency with a child. But the criminal charges against him were not for what Alissa or Angel had alleged. It wasn’t for anything Geneva had reported.

When officers searched Coffey’s home, the chief himself had mentioned a girl he talked with all the time. Investigators tracked her down. She was 14 years old. In court documents, she was called “Jane” to protect her identity.

Nearly two years later, Jane took the stand to testify about what the police chief had done to her.

Coffey was sitting feet away, in a tan jacket and blue shirt. She wasn’t used to seeing him without his uniform. She told the jury she was “scared to death.”

Jane, then 16, explained that she was a lonely home-schooled kid who often tagged along with her parents to work. Her dad made frequent trips to Maypearl City Hall, sometimes stopping by the chief’s office.

Soon after meeting Jane in 2014, Coffey was Skyping with the teen late at night. Over the next seven months, jurors would learn, the chief Skyped with Jane 106 times, including days before his arrest.

Jane believed Coffey was someone she could trust — someone who made her feel safe. “I cared about him so much,” she testified.

During their online chats, Jane confided that she’d recently been sexually assaulted by someone she knew. Then Coffey preyed on her, too.

In front of the camera, she told the jurors, he exposed himself and masturbated. In his messages, he described violent sexual acts he wanted to do to the teen. In the chief’s office, he penetrated her with his fingers. He usually left the door open.

“He liked the rush of it,” Jane testified.

To show Coffey’s grooming patterns, prosecutors had Alissa and Angel testify, too.

But when the former chief took the stand, he denied their allegations, saying he’d never abused anyone or exploited his authority. He conceded that, yes, he’d asked multiple people to try to persuade Jane’s family to drop the charges. And there was something else he was willing to agree with the prosecutor on.

When the former chief was ordered to spend 40 years in prison, Geneva sat in the back row, clapping.

A prison confrontation

Coffey had been in prison for more than six years when he agreed to talk to a reporter for the first time about what happened in Maypearl.

He’d never publicly apologized, never admitted he’d committed a crime. And even though he was found guilty of abusing Jane, he’d never had to reckon with the criminal charges involving Angel because that case was dropped.

His interview with The Post took place at a correctional facility in Rosharon, Texas, a four-and-a-half-hour journey from Maypearl through flat farmland and other communities that Coffey had once policed.

Beyond brick guard towers and layers of prison security, one question would finally be answered: What did the former chief have to say for himself now?

When Coffey was asked to describe himself in three words, he could think of only two: “introverted” and “compassionate.” He said he deeply missed his job and portrayed himself as someone who had made a positive impact as a law enforcement officer.

Once again, the former chief maintained his innocence. Coffey denied any criminal wrongdoing with Angel, Jane or Alissa, even when confronted with the evidence against him.

“The trial was all about character assassination,” Coffey said. “They used everything they could to make me look bad.”

Coffey also rejected claims that he harassed residents or retaliated against those who spoke out against him, including James Meyer. Though James’s daughter dropped her wrongful death lawsuit against Coffey after he was convicted, she still believes he bears some responsibility for her father’s suicide. Coffey blamed mental health issues and said he played no role in the man’s death.

In the hour-long interview, Coffey was dismissive of complaints lodged against him at other agencies. He defended his career in law enforcement, saying he kept switching departments for better pay, not because of poor performance.

As the interview came to a close, Coffey did make one admission.

“You know, thinking back, yeah,” Coffey said, “I should have left them alone.”

Coffey, now 59, still has more than 30 years left in his sentence. He told The Post that he was attacked by another inmate and transferred because of safety concerns. Prison officials would not answer questions about any violence or threats against Coffey. But they said the former chief has been moved eight times — about as many times as he changed police departments.

The lasting harm

Nearly a decade has passed since Alissa handed over her cellphone to Geneva. The teen never imagined what that single act would mean and how raw the wound would still feel all these years later. For her, for Angel, for Jane. And for the entire Maypearl community.

“I’m very pissed off. I don’t think that will ever change. … Do I trust anybody around me? Absolutely not.”

“I had to go forward, even if my story meant nothing to the trial. … Because these girls needed a voice, they needed someone to be there for them. And I didn’t have that.”

“I count how long it’s been since he’s laid a finger on me. And after seven years, all of your cells slough off. ... You’re a different person every seven years. And I think about that a lot, and I think that now, I’m in a body that he has never touched.”

After Coffey’s conviction, many in Maypearl lost trust in law enforcement. And no police chief, they said, has stuck around long enough to fix that. There have been eight chiefs since Coffey’s arrest.

Geneva is keeping count, of course, and keeping watch on what they do.

A few years back, Geneva was walking by the fire station on Main Street when she saw some city vehicles up for auction. She found the one that belonged to Kevin Coffey. Then she bid on his old black Tahoe and won.

The lights he’d used to flash into the windows of teenagers were removed. The Maypearl police logo was stripped away. But everyone still knew that cruiser had once belonged to the chief.

To banish all traces of Coffey, Geneva smudged the Tahoe with sage. Then she drove around her town, windows down, waving to everyone she passed.

“If you see something, say something. Stand up. Push back. I don’t care if it is law enforcement. … You have to stop it. Otherwise, what you allow will continue.”