As two social media influencers fight it out in court, a lawsuit over “sad beige” aesthetics sparks debate about creativity, commerce and copyright law.

By now, you’ve no doubt heard about the copyright lawsuit shaping up to be 2024’s version of “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?”: influencers Sydney Nicole Gifford and Alyssa Sheil are squaring off in court over who copied whose minimalist aesthetic on social media. The case is a bitter clash involving neutral-toned decor, Amazon affiliate links, and aggressively bland vibes.

My colleague Ken Basin—a far better lawyer and entertainment executive than a Who Wants to Be a Millionaire contestant—suggested I respond to The New York Times’ clickbaity headline, “Can You Copyright a Vibe?” by writing a simple one-word article: no. (In the spirit of shameless consumerism at the heart of this post, I returned the favor by offering to plug the Second Edition of Ken’s book, The Business of Television, now available for holiday gifting via my Amazon affiliate link.)

While the one-word suggestion was tempting, Google’s search engine overlords demand a bit more effort, and since Copyright Lately is all about SEO, I’ll offer a few more—fully aware that I’m a product of the same algorithmic forces fueling the dispute between Gifford and Sheil. Let’s be clear: this lawsuit isn’t about protecting art; it’s about safeguarding affiliate revenue streams. The fact that both Gifford and Sheil are hawking the same “sad beige” products says more about the commodified state of influencer culture than it does about copyright law.

That said, this is a copyright blog, and the legal question posed by The New York Times can still be answered in one word: no. You can’t copyright a vibe. That’s not to say people haven’t tried—and some have come close. In the Ninth Circuit’s 2018 “Blurred Lines” decision, the court upheld a jury verdict for a song that was, at best, evocative of Marvin Gaye’s signature style in “Got to Give It Up.” But Williams v. Gaye is now widely regarded as an outlier, and even the majority in that case emphasized: “Our decision does not grant license to copyright a musical style or ‘groove.’”

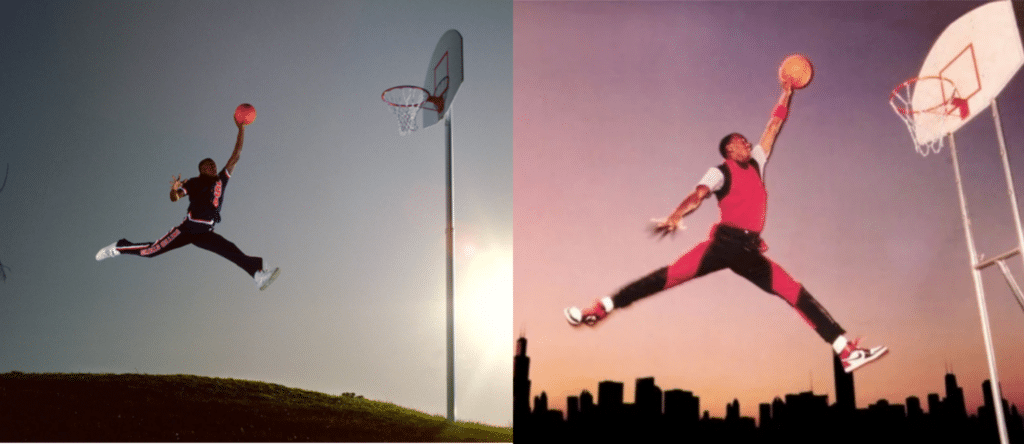

In dissent, Judge Nguyen went further, cautioning against allowing copyright to encroach on mere ideas or other unprotectable elements. “The purpose of copyright law,” she wrote, “is to ensure a robust public domain of creative works”—not to grant any one creator a monopoly over abstract stylistic concepts without substantially similar expression. That principle is particularly relevant here, given the “thin” protection that copyright law affords works like photographs that rely heavily on commonplace elements. These works are safeguarded only against virtually identical copying—not merely similar ideas, styles, or aesthetics. The Ninth Circuit reaffirmed this in 2018’s Rentmeester v. Nike, finding no infringement even though Nike’s “Jumpman” logo shared conceptual similarities with Co Rentmeester’s image of Michael Jordan.

This brings us to the photos at issue in Sydney Nicole LLC v. Alyssa Sheil LLC: influencers modeling products against pristine white walls, carefully arranging beige throw pillows, and unboxing tumblers on spotless coffee tables. These are textbook examples of scènes à faire—stock elements common to a genre—that lack the originality required for robust copyright protection in the absence of virtually identical copying. While Sheil’s photos may evoke a “single white female vibe” that feels unsettling, that’s not the same as copyright infringement. (To be clear, Gifford identifies as a white Hispanic woman, while Sheil is a Black Latina woman.)

What makes this case more fascinating—and, frankly, surreal—is the nature of influencer culture itself. It’s no coincidence that both Gifford and Sheil were promoting the same cable-knit sweater and faux-marble nesting tables; brands and platforms frequently provide curated lists of trending products for influencers to showcase to their audiences. These brands push the same items to multiple influencers, algorithms prioritize familiar aesthetics and audiences reward the recognizable. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle of sameness. Viewed through that lens, the beige-on-beige aesthetic isn’t so much a creative choice as an inevitable byproduct of a broader marketing machine. Imitation isn’t just foreseeable; it’s practically baked into the system.

To be sure, many of Sheil’s posts do resemble Gifford’s—she may have even intended to evoke a similar vibe. However, there’s no evidence that Sheil copied any of Gifford’s actual images or videos, and hundreds of other “sad beige” influencers are churning out similar content in lockstep. More likely, their posts look alike because they feature the same products against similarly styled backdrops, all striving to embody the so-called “clean girl” aesthetic: neutral tones, minimalist decor, spotless white surfaces, and a curated sense of calm that teeters on sterile.

For now, Gifford’s copyright claims have been allowed to proceed to discovery, with the magistrate judge observing that the case “appears to be the first of its kind” in which one influencer accuses another of copyright infringement based on the similarity of posts promoting the same products. Whatever the ultimate outcome, there’s undeniable irony in two influencers battling for ownership of content so generic, bland and relentlessly average it might as well have been generated by AI. That’s not to say these human-crafted social posts aren’t protectable—they are, just not by much.

While this particular influencer battle will likely settle—most cases do—perhaps a better long-term outcome would be a legal decision that disabuses influencers of the notion that anyone can claim ownership over banality. After all, when your business model hinges on convincing people to buy tumblers and throw pillows they don’t really need, the real victory may be that anyone’s paying attention at all.

Of course, that’s just my take. Let me know yours in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. Meanwhile, here’s a pristine off-white copy of the magistrate judge’s recommendation, recently adopted by the district court in the Gifford/Sheil dispute.

View Fullscreen

1 comment

The one-word article idea reminds me of Betteridge’s Law: “Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.”

https://thekeypoint.org/42-2/