HOYT LAKES — For the last 23 years, the former Erie Mining Co. concentrator has sat dormant. But since last summer, the quarter-mile-long building has been humming with activity again.

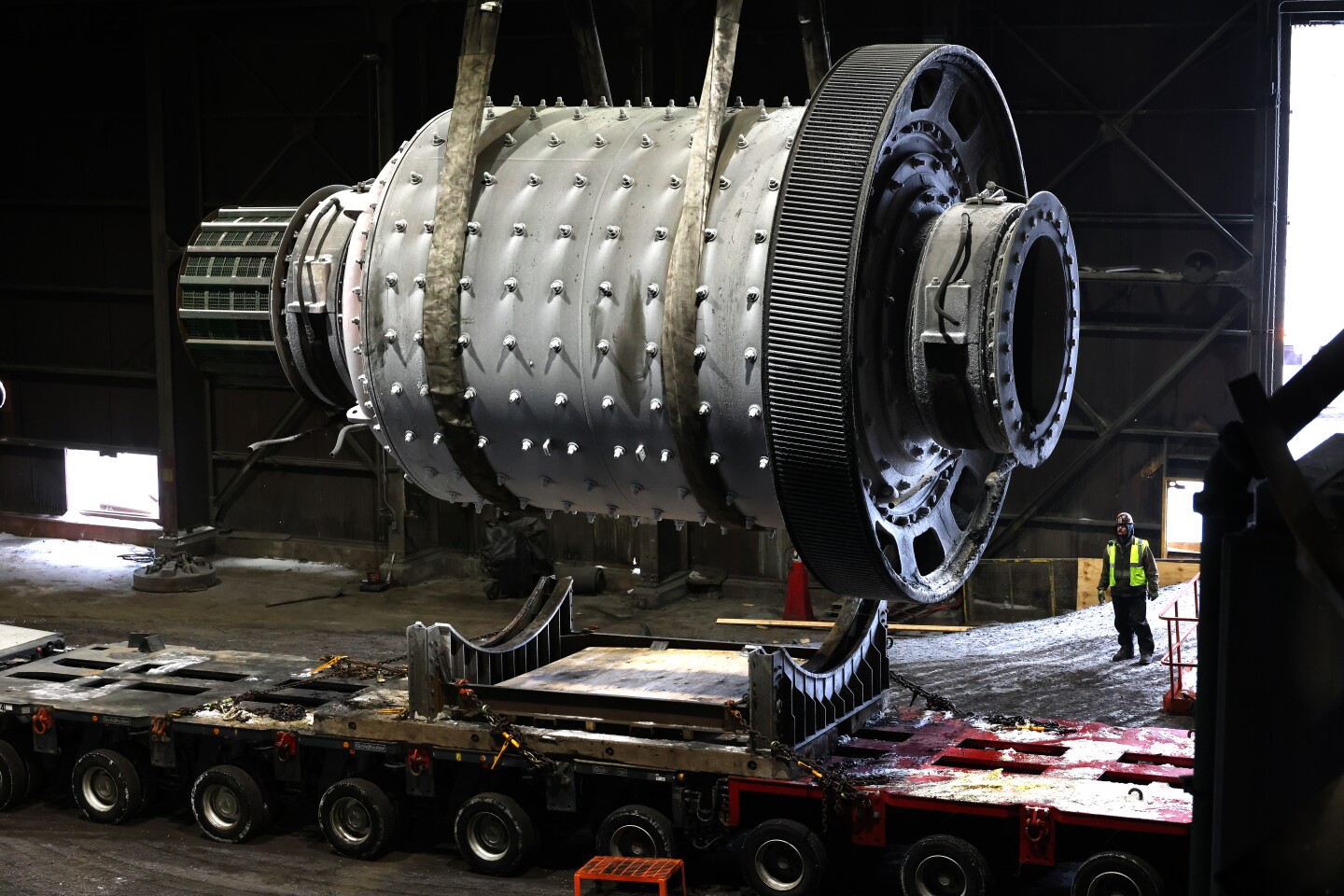

The overhead crane spanning the building is up and running, hoisting each of the 64 190-ton ball and rod mills and carrying them across the concentrator to a remote-control flatbed, which carries the mills to a scrapyard to be dismantled, separated into different alloys and taken to a recycling facility.

The building itself will remain but made more cavernous — and brought back down to the bedrock it was built on nearly 70 years ago — by an excavator with cracker jaws that easily pulled apart several stories of steel and concrete platforms that once held the mills.

Crushed taconite left behind when the mine and processing plant closed under LTV Steel Corp. ownership in 2001 — laying off 1,400 workers — has been pulled from the building’s fine ore storage areas and placed across a bed of crushed concrete to make road surfaces onsite.

NewRange Copper Nickel, a joint venture between Glencore and Teck, is making room in the former taconite concentrator for a processing facility that it hopes will one day separate copper, nickel and other minerals from ore mined at the nearby NorthMet deposit.

But faced with regulatory uncertainty, prep work on site is limited to the removal of old equipment, roof repair and other related projects.

Last year, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers revoked the federal discharge permit because it said it did not ensure compliance with the standards of the downstream Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency is revisiting the project's water permit after a court said it did not adequately consider federal regulator concerns that it may not comply with the Clean Water Act, and an administrative law judge recommended the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources deny the project’s permit to mine because its planned method of storing waste rock was not “practical” or “workable.”

NewRange has maintained it is committed to regaining its permits.

“The demolition portion of the work will prepare the building to be ready for construction when the project is sanctioned, so this will kind of give us a jump on our construction timeline,” NewRange senior mechanical engineer Michael Glissman said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Built between 1954 and 1957, the Erie concentrator received taconite after it was mined and crushed. The concentrator and all its mills pulverized ore into particles so the iron could be separated and moved to the pellet plant, where it would be made into marble-sized pellets, loaded onto a train and then shipped across the Great Lakes to a steel mill. The waste rock — tailings — were sent to a massive nearby basin.

When LTV closed, it left the plant in a state that would have allowed a restart, and when NewRange, then PolyMet, acquired the plant in 2005, it intended to use some of the old mills.

“But over the years, the technology has improved,” said Glissman.

Now, the mills are coming out. As of last week, 25 of the 64 mills had been removed, and a 25-person crew has managed to remove up to three mills per day.

If it becomes operational, NewRange intends to install two much larger mills — one with a 34-foot diameter and 21-foot length and the other with a 24-foot diameter by 37-foot length.

For comparison, each of the existing taconite mills has a diameter of 12 ½ and a length of 14 feet.

Once the mills are brought to a nearby salvage yard, crews use blow torches and wrecking balls to pull them apart and sort the metals, mostly different types of steel and some bronze.

ADVERTISEMENT

Most scrap will go to recyclers in the Duluth-Superior area, and the mills’ high chrome white iron liners, a part that requires periodic replacement, will likely end up at the ME Elecmetal foundry in Duluth where they were first made, and where they will be remelted into new liners for one of the six operating taconite plants on the Iron Range, Glissman said.

The project is expected to cost $18 million and, depending on the scrap market, recover about $5 million in scrap, Glissman said. It’s believed to be the largest recycling project in the state right now, and is likely one of the largest in state history, using some 19,000 tons of ferrous scrap metals, 44,000 cubic yards of concrete and 80,000 tons of taconite ore.

That makes sense considering the construction of the former taconite mine and plant — all the processing facilities in Hoyt Lakes, railways and the Taconite Harbor coal plant and loading dock on Lake Superior — had a $313 million price tag, marking the largest private investment in U.S. history at the time, according to a Wall Street Journal article. That’s more than $3.5 billion in today’s money.

Ron Hein, 86, started at Erie in 1960 as a welder and steel fabricator and advanced to director of organizational development before he left in the late 1990s.

When the concentrator building was in use, it was “humid and extremely noisy” inside with so much water used in the process and all the grinding mills spinning, Hein said.

He said he was glad to see the concentrator building remain. Other structures on site have faced a different fate. Much of the pelletizer was destroyed in 2007 by a salvage company, for example (NewRange said it removed some 8,000 cubic yards of material from an onsite landfill last fall related to that pellet plant’s demolition).

“To know (the concentrator buildings) are being repurposed, reused, that’s a good thing,” Hein said. “If they were actually being demolished, again, that would be sad — another milestone, if you will, in the demise of Erie Mining Company’s processing plant.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The former Erie plant means a tremendous amount to Hein and others, whether they built it, worked at it or grew up beside it in Hoyt Lakes. More than 10,000 people worked at Erie over its 44-year run.

Hein, of Duluth, served as project manager for the Erie History Project, which culminated in the 2019 book, "Taconite, New Life for Minnesota's Iron Range: The History of Erie Mining Company." The project has also made its book and additional materials available to classrooms and libraries.

As part of the project, Hein and others conducted more than 150 oral history interviews.

“There was no one who ever said that Erie was a bad place to work,” Hein said as he choked up. “It was a close-knit community.”

This story originally contained the incorrect number of operating taconite plants on the Iron Range. It was updated at 9:26 a.m. Jan. 30. There are six taconite plants in operation. The News Tribune regrets the error.