Marie* was 14 years old and enrolled in a Christian school when she met and became involved with Miguel, a Brazilian soldier working in Haiti as a UN peacekeeper. When she told him that she was pregnant with his baby, Miguel said he would help her with the child. But instead, he returned to Brazil. Marie wrote to him on Facebook but he never responded.

After learning that she was pregnant, Marie’s father forced her to leave the family home and she went to live with her sister. Her child is now four and Marie has yet to receive any support from the Brazilian military, an NGO, the UN or the Haitian state. Marie provides what she can for her son but she cannot afford to send him to school. She works for an hourly wage of 25 gourde (around 26 US cents or 20 UK pence) so that she and her son can eat. But she needs help with housing and paying for school fees.

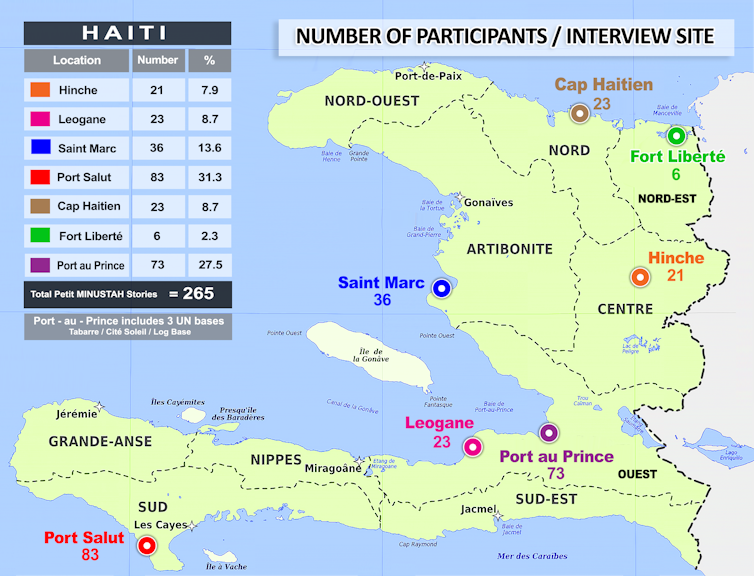

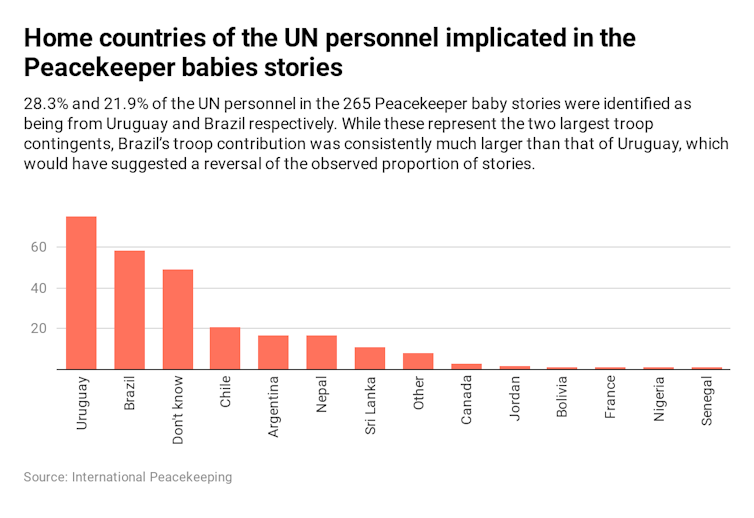

Sadly, Marie’s experience is far from unique. In the summer of 2017, our research team interviewed approximately 2,500 Haitians about the experiences of local women and girls living in communities that host peace support operations. Of those, 265 told stories that featured children fathered by UN personnel. That 10% of those interviewed mentioned such children highlights just how common such stories really are.

The narratives reveal how girls as young as 11 were sexually abused and impregnated by peacekeepers and then, as one man put it, “left in misery” to raise their children alone, often because the fathers are repatriated once the pregnancy becomes known. Mothers such as Marie are then left to raise the children in settings of extreme poverty and disadvantage, with most receiving no assistance.

Mired in controversy

The UN Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) – the longest running mission by the organisation in the country (2004-2017) – was originally mandated to assist local Haitian institutions in a context of political instability and organised crime. Its mandate was then extended due to natural disasters, most notably an earthquake in 2010 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016, both of which added to the volatility of the political situation in the country. After 13 years of operation, MINUSTAH closed in October 2017, transitioning to the smaller UN Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH).

MINUSTAH is one of the most controversial UN missions ever. It has been the focus of extensive allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse. A shocking number of uniformed and non-uniformed peacekeeping personnel have been linked to human rights abuses including sexual exploitation, rape, and even unlawful deaths. (For the purposes of this article, we use MINUSTAH personnel, agents, and peacekeepers interchangeably to refer to uniformed and non-uniformed foreign staff associated with MINUSTAH.)

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

With regard to public health, it is undisputed, and now officially recognised by the UN, that peacekeepers also inadvertently introduced cholera to Haiti. More than 800,000 Haitians are known to have sought medical attention for cholera and at least 10,000 died from the disease.

Various media organisations have reported that minors were offered food and small amounts of cash to have sex with UN personnel, and MINUSTAH was linked to a sex ring that operated in Haiti with seeming impunity: allegedly, at least 134 Sri Lankan peacekeepers exploited nine children in a sex ring from 2004 to 2007. As a result of this story, reported by the Associated Press in 2017, MINUSTAH became a classic example of lack of appropriate response to allegations of sexual abuse. In the wake of this report, 114 peacekeepers were returned to Sri Lanka, but none were ever prosecuted or charged after repatriation.

Extensive research has demonstrated that children born of war are often raised in single-parent families in precarious economic post-conflict settings. The association with the (absent) foreign father, along with birth out of wedlock, often result in stigma and discrimination for the children.

Yet little is known about the impact of being a mixed-race child fathered by peacekeepers. Even less is known about the experiences of the so-called “Petit MINUSTAH”, or Haitian-born children of foreign UN peacekeepers. This is one of the reasons we set out to bring to light the stories of those affected by the UN mission.

Our study

We collected stories by asking participants to tell us what it’s like to be a woman or girl living in a community that hosts a peacekeeping mission. We audio-recorded the resulting stories, and then participants interpreted their experiences by responding to a series of pre-defined questions. This allowed us to better understand the circumstances and consequences of their interactions with peacekeepers.

Participants could share any story they chose, about anyone, and were not prompted in any way to talk about sexual abuse or exploitation. Narratives were captured by trained Haitian research assistants in the communities surrounding ten UN bases in Haiti in the summer of 2017. About 2,500 Haitians were asked about the experiences of local women and girls living in communities that host peace support operations. A variety of positive and negative experiences were captured, but 265 (10%) of all stories were about peacekeeper-fathered children. This is particularly noteworthy since the survey did not ask about sexual relations with peacekeepers or about children conceived through such relations.

This would suggest not only that sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeeping personnel is not rare, but also, as one Port-Salut research participant said in her own words: “There are many young women who have children with the MINUSTAH.” This was echoed by a man in Saint Marc who told us: “MINUSTAH gave us many children without fathers.”

Some stories were first person, shared by those who had given birth to children fathered by UN personnel, while other stories were told by family members, friends or neighbours about women and girls raising children fathered by peacekeepers. To the best of our knowledge, these stories make up the first empirical research to bring forth the voices of families affected by sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers.

Sex for one meal

Some sexual encounters between local women and girls and UN peacekeeping personnel were described as sexual violence. For instance, a male community member in Cité Soleil recounted:

All day, I heard women who are complaining about the sexual violence that MINUSTAH did to them. And they had given them AIDS through sexual violence. There are also some of them who are pregnant.

There were not only stories of women and girls being sexually assaulted by MINUSTAH but also of men and boys being similarly abused. But in our research, sexual assault was in the minority of reported sexual encounters. Instead, our data highlighted a much more pervasive problem, albeit one that has been reported less in the media – transactional sex with UN personnel.

One married man from Cité Soleil described a common pattern in which women received small amounts of money in exchange for sex: “They come, they sleep with the women, they take their pleasures with them, they leave children in their hands, give them 500 gourdes.”

In other cases of transactional sex, women and girls received food in exchange for having sex with members of MINUSTAH, highlighting the extreme poverty that contributes to these sexual encounters. One male community member in Port Salut reported: “They had sex with the girls not even for money, it’s just for food, for one meal.”

Evolving relationships

Another narrative that has received far less attention in previous reports is how consensual sexual relations between members of MINUSTAH and local women evolve. In some instances, these were casual dating relationships that resulted in a pregnancy, as was the case in this story, shared by a man in Port Salut:

I had a sister who was dating a MINUSTAH soldier. My whole family knew about it, my mother as well as other people. She became pregnant … Ever since, my sister’s life is a mess.

Other relationships were described as being more committed and loving, such as in this story shared by a woman in Cité Soleil, who said: “I was living in Cité Soleil and I was in a love relationship with a MINUSTAH. I became pregnant from him.”

We found that intimate relations with fair-skinned peacekeepers and having fair-skinned children were sometimes perceived as desirable. A woman in Leogane described “rumours” about girls having relationships with MINUSTAH and having their children because they “wanted these children to be beautiful”.

Regardless of whether the relationship was consensual or transactional in nature, particular patterns were noted in how and where the interactions took place. For instance, meeting on the beach or in a hotel was common, as in this story shared by a woman in Cité Soleil, about a friend of hers: “He used to go to the beach with her, now the white man paid for a hotel for her, the white man goes to the hotel with her, he comes to have sex with her.”

Also of great concern is that many of the mothers giving birth to and raising children fathered by UN peacekeepers were themselves adolescents and not old enough to give consent for sex. One woman in Cité Soleil told us:

I see a series of females 12 and 13 years old here. MINUSTAH impregnated and left them in misery with babies in their hands. The person has already had to manage a stressful, miserable life.

Abandonment

After learning of a resultant pregnancy, most shared stories indicated that the MINUSTAH personnel were repatriated by the UN. One woman in Port-Salut told us:

One of my sisters gave birth to a child of the MINUSTAH. My sister had a baby with him because she met him, fell in love with him, he took care of her, but you know, they were sent away. That is why he stopped sending her things.

A male participant in Hinche described a similar experience for a girl he knew, saying: “She was pregnant from a soldier of the MINUSTAH … [He] was moved from his station and left his post and was never seen again.”

After the departure of the peacekeeper fathers, most young women were left alone trying to raise the children in extreme poverty. Some described being fortunate enough to receive support from their families, although certainly not all.

In almost all cases, access to education was beyond the mother’s or the family’s means, as described by one woman in Port Salut:

I started to talk to him, then he told me he loved me and I agreed to date him. Three months later, I was pregnant, and in September he was sent to his country … The child is growing up, and it’s myself and my family that are struggling with him. I now have to send him to school. They put him out because I’m unable to pay for it.

A man in Cap Haitian said:

The soldiers destroy these young girls’ futures by getting them pregnant with a couple of babies and abandoning them. Basically, these actions of the soldiers can have a negative impact on the society and on the country in general because these young girls could have been lawyers, doctors or anything that would have helped Haiti tomorrow … Now some of them are walking in the street, or in the flea market and other places with a basket over their head selling oranges, peppers, and other goods in order to raise children they have with the MINUSTAH soldiers.

In a few extreme cases, community members described women and girls who were left with little option other than to engage in further sex with peacekeepers in order to provide for the MINUSTAH children they were already raising. A man in Port-au-Prince shared one example:

He left her in misery because when he used to have sex with her it was for little money, now his term reaches its end, he goes and leaves her in misery, and then now she has to redo the same process so she can provide meals to her child, can’t you understand.

There were many requests in the stories we collected for MINUSTAH and the Haitian authorities to help support these children. One man in Port-Salut stated his request very clearly: “I would like to ask the head of MINUSTAH to take responsibility for the children of MINUSTAH members … We are just doing what we can but you cannot raise children like this…”

Power and exploitation

Our research has underlined what is implied in much of the academic literature on peacekeeping economies – namely that poverty is a key underlying factor contributing to sexual abuse and exploitation by peacekeeping forces.

In many cases, the power differential between foreign peacekeepers and local populations allows foreigners, knowingly or unknowingly, to exploit local women and girls. The prevalence of transactional sex in our data underscores the significance of the structural imbalances – peacekeepers have access to some of the resources that are desired or needed by the local population and so they are in a strong position to exchange those for sex.

While many of the stories cited above were collected in Port Salut and Cité Soleil, similar narratives were shared across all interview sites in Haiti and the phenomena described are not unique to the Haitian context. Our preliminary work in the Democratic Republic of Congo suggests a comparable situation.

In its zero-tolerance policy, the UN acknowledges the existence of socioeconomic and other power imbalances and their potential to render “intimacies” between peacekeepers and local women exploitative. In essence, the policy bans almost all sexual relations between peacekeepers and local women. In addition to suggesting that this blanket ban is ineffective, our data indicates that a more nuanced approach with targeted training of UN personnel is required alongside tackling the impunity that still surrounds peacekeeper wrongdoing.

Another key finding is the need for more effective mechanisms allowing victims of sexual exploitation and abuse and their children (as well as children of consensual and non-exploitative relations) to access support. This could potentially break the socioeconomic downward spiral that traps victims – and in particular children – in circumstances of extreme economic hardship, perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

Child support

In January 2018, the Haitian-based Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI) filed paternity suits in Haitian courts on behalf of ten children fathered by UN Peacekeepers, with the aim of lobbying the UN to secure child support payments for those children. A year later, an open letter from the bureau to UN Victims’ Rights Advocate Jane Connors betrays their frustration with the UN’s lack of responsiveness and co-operation in the paternity suits, which “has made it nearly impossible for our clients to obtain justice”.

Evidencing the UN’s refusal to furnish results of DNA paternity tests that are vital to the mothers’ cases despite a Haitian court order compelling it to do so, the letter concluded that the UN was sending “an alarming message of lack of respect for the Haitian judicial system and the rule of law”.

This raises questions regarding the UN’s rhetoric about supporting the dignity and rights of those affected by sexual exploitation and abuse perpetrated by UN peacekeepers. It also calls into question the effectiveness of interventions of the Office of the UN Victims’ Rights Advocate, which exists to advocate for the rights of victims and to bring their needs to the forefront of the UN’s fight against sexual exploitation and abuse.

Recommendations

The findings from our research have led us to make three key recommendations.

1) Training of UN personnel must include a cultural awareness aspect to enhance understanding of the impact of power differentials in fragile peacekeeping economies, the perceived desirability of having a child fathered by a peacekeeper, and the socio-economic consequences for a vulnerable woman being left with a peacekeeper-fathered child.

2) The UN practice of repatriating any UN personnel implicated in sexual exploitation or abuse must stop as it has a double-negative consequence. First, it removes the alleged offender from any effective prosecution in the cases of alleged wrongdoing, and second, it removes them from any jurisdiction within which the victim/child/mother of a child would have any chance of securing the appropriate financial support for the child.

3) The recent appointment of a Victims’ Rights Advocate for those affected by sexual abuse and exploitation must be followed by a policy that will allow the advocate to tackle some of the injustices created by the exploitation and abuse at a structural level. At the same time, they must be allowed to become a powerful voice of the victims, speaking and working on their behalf within the UN and in collaboration with the host countries and the troop contributing countries.

Many of the participants interviewed expressed similar sentiments around the need for recognition of and support for children fathered by UN peacekeepers in Haiti. One man said:

I know a lot of young women, young girls, children, who are living with MINUSTAH children in their care… I would like for them [the UN] to take responsibility, to take the initiative to look for and rejoin those young girls so that they can help them with the children.

* Names have been changed to protect participants’ anonymity.

For you: more from our Insights series:

Environmental stress is already causing death – this chaos map shows where

Charles Dickens: newly discovered documents reveal truth about his death and burial

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Comments are open on selected articles and must comply with our community standards.