By Richard and Janis Hudson

“If you want to talk to someone local about Loma Sandia, ask Jimmie Harrod. He’s the one who knows,” said Kip Dove, who made his career with the Live Oak County Highway Department and has a lot of respect for the man who was his early mentor.

Oakville resident Harrod remembers “The Dig,” but when asked recently in a telephone interview about Loma Sandia, he said, “We just called it ‘the dig!’Never heard it called Loma Sandia before now. Around here ‘the dig’ is how most people remember the old Indian Cemetery.”

Frank Weir, a retired state highway department archeologist who lives in Bastrop, was the principal investigator of the Loma Sandia Site. He said it was common practice for the department to assign a name and number to archeological excavations in the state. Because the site was a sandy mound or small hill on which a local farmer grew watermelons, the site was named Loma Sandia.

“Loma,” Spanish for “hillock” or small hill or mound, and “sandia,” as most know, means watermelon. The official archeological number assigned was 41LK28. Texas is signified by 41, LK stands for Live Oak County, and 28 is the site number. Somehow, this didn’t get conveyed locally, so the folks in Live Oak County just called it “the dig” because a whole lot of digging was required to preserve the bones and artifacts in the prehistoric cemetery before Interstate Highway 37 could be built.

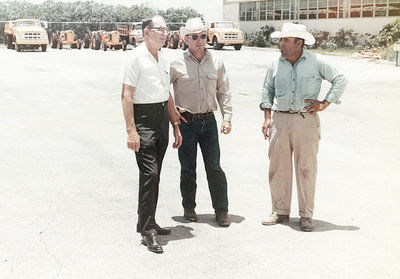

Sometime around the early 1970s, Harrod received word from Live Oak Resident Engineer, Francis “Buster” Smith, that the Highway Department was sending a team of archeologists down from Austin to explore a patch of land in the path of Interstate 37 for artifacts. Smith was son of Albert Smith, a well-known Live Oak County Sheriff who served the county from 1927 to 1965. Smith passed responsibility for the archeological team on to Harrod, who at the time was Superintendent for the Live Oak County Maintenance Department.

“Of course, then,” Harrod said, “I was called foreman instead of superintendent, a fancy title the highway folks up in Austin hadn’t come up with yet. But when Buster passed the order to me, it was my responsibility to see these archeologists got what they needed, account for it, and pass that information on back to the main office who sent money down to pay for everything.

“It was a tall job,” Harrod said, “and it became more so as this team of investigators discovered that local farmers were uncovering Indian artifacts when plowing their fields.”

According to Harrod, this took some time, but by the mid-1970s or a little later the highway department began “The Dig” off Hackberry Creek just south of the junction of U.S. Highway 281 and old Highway 9. The actual work at the site began in September 1977 and was completed in October 1978. All work was restricted to January 5, 1972 guidelines set in a Memorandum of Understanding between the Highway Department and Texas Antiquities Committee.

The excavation delayed completion of Interstate Highway 37 for about four years, and Harrod’s job included paying the project team and supporting them with heavy digging equipment, shovels and wheelbarrows, clerical supplies, trowels and buckets, brushes, even pencils and, finally, unskilled labor for moving dirt.

Harrod placed ads in the local and regional newspapers for unskilled laborers. He hired 45 men and women from Live Oak County. To support the workers and maintain safety standards, he made at least two trips a day to the site.

“They almost ruined my safety record right off,” he said. “Headaches, sore toes, and sunburn just shot that record to smithereens. We were sending four to six to the doctor’s office every day. I had to set up additional safety training in a hurry. But I managed to bring it under control.”

Thirty more employees added to Jimmie’s payroll, which included university archeology students, their professors and professional archeologists from Austin.

“The student list changed from semester to semester. They lived in rent houses and trailers in Three Rivers and George West. The archeologists worked ‘the dig,’ Harrod said, “and supervised the students. Most of the archeologists came from the Texas State Highway Department and The University of Texas.

Among Jimmie’s memories was the immense effort the archeologists gave to keep thorough records.

“As human bones were found,” he said, “they would be carefully sprayed with a chemical and wrapped with plastic overnight. The next morning, the bones looked similar to weathered wood and were photographed and recorded.

“Then the most astounding thing happened,” Harrod said, “the skeletons would literally evaporate in front of your eyes! Just vanish into thin air without leaving even a vapor! The last things to disappear were the lower jaw bone and the teeth. It was just the most amazing thing I ever saw!”

Harrod’s brother, Wood, was teaching school, but spent time at the dig on weekends. Students and workers lined skeletal remains up before Dr. Maciej Henneberg, an anthropologist from Poland and visiting lecturer at UT Austin.

“With a few taps of a pick and brush on the skeletal remains,” Wood said, “Henneberg identified age, gender, and cause of death, like a fifteen year old male killed with the blunt side of a heavy rock.”

Harrod likes to refer to himself as an “April Fool”. He was born April 20, 1939.

“Many of my life’s events,” he said, “came to me in that month.”

He received his first job, April 1960, transferred to Live Oak County Highway Department, April 1965, and was promoted to Maintenance Foreman, April 1971.

Little did Harrod dream that 44 years later one of his greatest projects, Loma Sandia, ‘The Dig’ would have a Texas Historical Marker unveiled on April 19, just one day before his next birthday. He thought that was a hoot!

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In