The sky is falling, the sky is falling! Well, maybe it's not that serious, but after a decade of warnings that we'd soon be running out of IPv4 addresses, that day has finally come. North America is now, officially, out of IPv4 addresses.

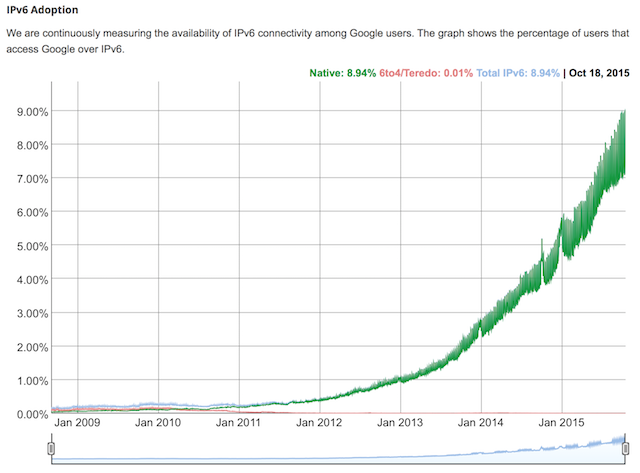

The changeover from IPv4 to IPv6 is already underway but adoption is slow -- even after all of the addresses have been taken. Let's take a look at what this means for you and how you can be part of the change.

What Is IPv4, Anyway?

IPv4 came before IPv6, so it's important to understand IPv4 before we can understand why IPv6 is so important.

It stands for Internet Protocol Version 4. Every Internet-connected device and every website on the Internet is assigned a unique numerical address, or IP address. This address is what allows devices and websites to find each other when communicating back and forth.

IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses, which means that there are a total of 2^32 available addresses (approximately 4.29 billion if you're too lazy to do the math). North America has now exhausted all of those available IP addresses, which means we need to look for another way to assign addresses to devices.

IPv6 solves this problem by using 128-bit addresses, which allows for a total of 2^128 available addresses (approximately 340 trillion trillion trillion -- or 340 with 36 zeroes following behind it). To put it mildly, this is, well, significantly more than the 4.29 billion IPv4 addresses we've exhausted.

Why Haven't We Switched Yet?

Unfortunately, switching from IPv4 to IPv6 isn't as simple as flicking a switch that turns off IPv4 and flicking another switch that turns on IPv6. The two aren't compatible with each other and it's impossible to translate between the two protocols on the fly.

Luckily, researchers have found a solution of sorts: a special gateway that allows you to run both IPv4 and IPv6 at the same time. The process is called dual stack.

Mac and Windows computers have had this technology for years, and most modern mobile phones do as well. The problem with adoption is in legacy technology, such as routers, which people might not upgrade for years at a time.

Modern routers support IPv6, but too many people are still using outdated hardware. Those who own their own routers need to go out and buy new ones. Those who lease their routers from ISPs need to wait until said ISPs send them upgraded routers.

This means that even if your device is capable of IPv6, it may not be using it. For example, even though an iPhone 6s is IPv6-capable, the five-year-old router it's connected to might not be -- thus the iPhone 6s still relies on IPv4.

Websites have the same issue. Not only are server upgrades with hosting companies expensive, many website owners aren't able to simultaneously serve IPv4 and IPv6 visitors, which would mean cutting off traffic to IPv4 visitors -- something they aren't willing to do.

But there are some early adopters out there that offer full IPv6 support, such as:

- Netflix

- Sony Japan

- Microsoft

- NASA

- YouTube

- Comcast

- AT&T

- Sprint

- Porsche

Another reason we've been slow to adopt the new standard is because IPv6 is still in its infancy. That is to say, it's still imperfect and there are some hiccups that we'll have to overcome before it works as intended.

The Impact on Consumers Like You

For the most part, this won't really affect consumers in that there isn't much you can do. The onus falls on device manufacturers and ISPs to get caught up. That said, the cost of acquiring an IPv4 address has recently gone up, so if we do see any major consumer issues, it's probably going to be in pricing.

With IPv4 addresses exhausted, companies that haven't made the switch still have options. Currently, they can:

- Join a wait list for freed up IPv4 addresses. (Not likely.)

- Switch to IPv6 completely. (99.67% of IPv6 addresses are still available.)

- Purchase IPv4 addresses from someone else.

Of these options, tech companies are largely opting for number three. As demand goes up, these are going to get more expensive, which could start to be reflected in web services (e.g. hosting), device prices, and bigger bills from your ISP.

But wait. If companies can buy new IPv4 addresses, why do we need to worry about IPv6 at all? Can't we just continue recycling IPv4 addresses? Well, it's not that simple.

Inevitability

At some point, the worldwide availability of IPv4 addresses is going to be exhausted. Every single address in the world will be occupied and the wait list will become pointless. The changeover to IPv6 will happen at some point.

Security

IPv4 just isn't that secure in the grand scheme of things. We have more online threats today than ever before, and we're starting to see the limitations of IPv4 from a security standpoint.

IPv6 encrypts traffic, checks network data integrity, and a bunch of other things that are far too complex to sum up in a few words here. Simply put, it takes on a lot of the features of current VPN technology -- which you should be using -- and keeps you safer than standard non-protected web browsing.

Efficiency

IPv6 is downright more efficient than IPv4. In fact, for the Web to move onto the next level, we need IPv6.

There's a lot to explain behind IPv6's efficiency, but here's the important part: it moves your data around faster (smarter handling of data packets) and it checks to ensure that data hasn't been tampered with during transit (built-in packet integrity checks).

All of this is slow in coming, but eventually the entire Web will exclusively switch to IPv6. IPv4 will always remain for legacy support, but the sooner IPv6 is adopted, the sooner we'll see a new and improve Internet for consumers all over the world.

Did this help clarify things for you? Will you be upgrading to IPv6 hardware now? Or have you done so already? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below.