The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

To the customers at the branch of Sainsbury’s supermarket in Clapham, South London, where he worked part-time towards the end of his life, Shahin Shahablou was simply an incredibly helpful member of staff. They had no idea who he was or what he had endured.

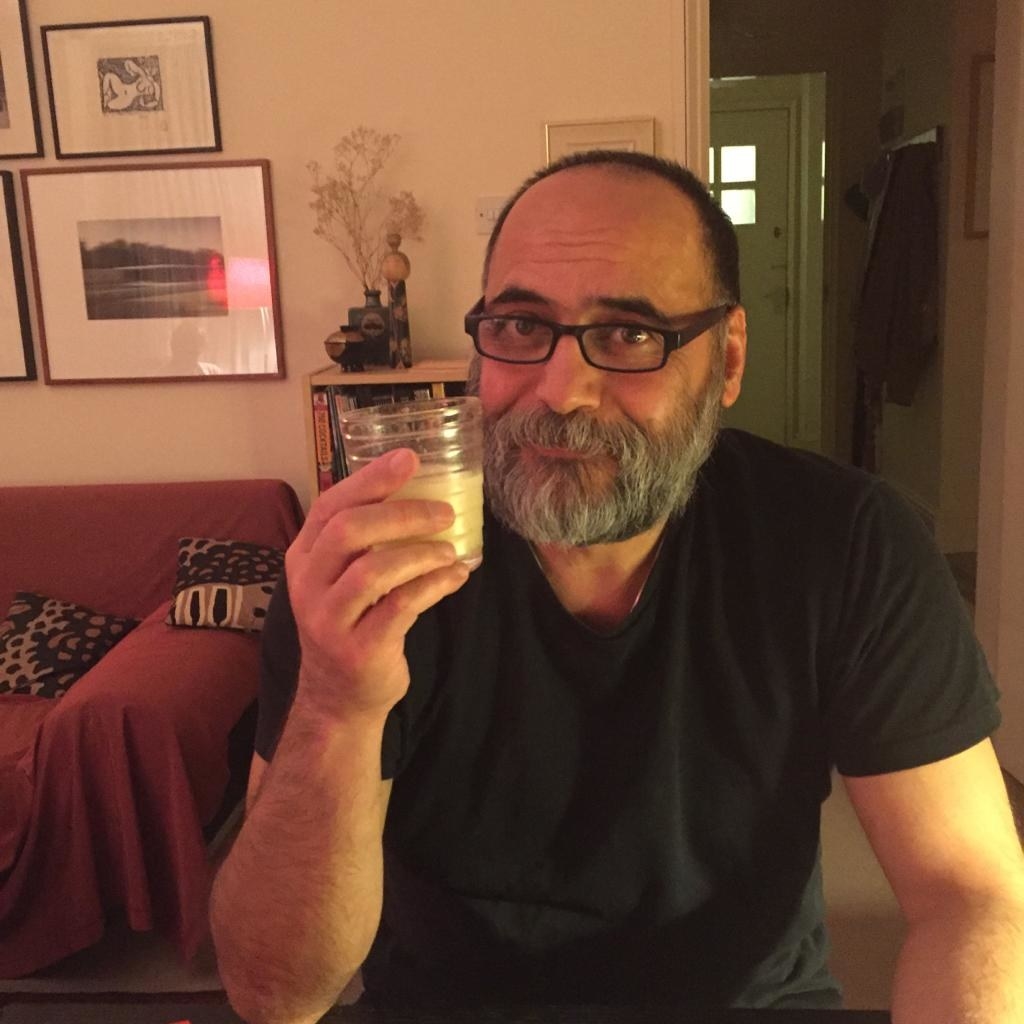

Shahablou, who died of the coronavirus aged 56, had been a political prisoner in Iran, where he grew up. He finally left for Britain in 2011 in order to be himself — to be gay. After gaining refugee status, he became an award-winning photographer, known for capturing the hidden essence of his subjects, many of whom were from the LGBTQ community, often people who had been overlooked. But he didn’t just come to London to be free.

“He really wanted someone that he could share his life with,” Kevin Lismore told BuzzFeed News. Shahablou and Lismore had begun dating just months before his death. “He said he would never be able to find a partner there in Iran, that it would just be sex. But he wanted a partner for life.”

In Lismore, Shahablou found the person he had wanted to be with. “There was something very special happening between us," said Lismore. "He kept telling me how he felt like it was destiny that we met each other.”

On April 15, after he'd spent 19 days in intensive care, Shahablou’s organs failed. The love for which he had spent his life searching, and for which he had left his family and motherland, would be cut short.

“That’s the cruellest thing, to lose him so soon,” said Kevin. “It feels really unfair on him and me, and on his friends and family. It’s tragic.”

Shahablou’s five sisters and one brother remain in Tehran. According to his closest friend, David Gleeson, they considered repatriating him. “But over the weekend they all talked about it and decided that he loves London so they want him to stay here,” he said. Their decision, a mark of respect for the life and country that he chose, means that they will not, owing to lockdown and travel restrictions, be able to attend his funeral. His death has shocked his loved ones.

“I can’t get my head around it,” said Gleeson. “At the age of 61 and having lived through the AIDS epidemic, I should be used to people disappearing. But I feel really desolate. I’ve realised since he died just how much I loved him.”

Gleeson lives in Soho, central London, where Shahablou loved to spend time, finding his own microcommunity in the patrons of the King’s Arms pub, loved by bears — bigger, hairy gay men that Shahablou also photographed. “In the deserted streets I see him everywhere,” said Gleeson. “I’m just so used to seeing him around here.”

All who spoke to BuzzFeed News about Shahablou, both loved ones and those he photographed, describe a man of utmost sensitivity who felt others’ pain as his own, who searched always for meaning and depth in his work and relationships, and whose determination enabled him to finally find the life that had long eluded him.

Shahin Shahablou was raised in Tehran in a close-knit family. His love of photography led to a bachelor’s and then a master’s degree in the subject from the University of Tehran. His career blossomed over the course of two decades. He taught photography, enjoyed solo exhibitions in Iran and India, became a photojournalist and a board member of the Iranian Photojournalists Association. Later, in Britain, he was a freelance photographer, shooting for Amnesty International, among others.

But he had two problems, according to Gleeson, both of which led to financial hardship: Shahablou was so modest that he found it unbearable demanding the fees for his work that he deserved. And he believed so much in pursuing meaningful assignments that he would sometimes decline the more commercial. "He wouldn't just take on any project," said Gleeson. “Some rich woman who lived in a mansion in Regent’s Park wanted him to come and take portraits of her kid and he said, ‘This is the kind of job that bores me.’ He just passed it on.”

Instead, he focused on intimate, sometimes painful subjects from which others might shy away.

“When Iranian Muslims die there is a particular ceremony where the body is washed, so he went to a part of Iran and filmed the place where this happens,” said Gleeson. “He produced this fascinating photo essay.”

Shahablou’s determination to pursue a career of meaning rather than money led to many periods of financial instability, poor housing, and eventually his need to work in a supermarket. But he never stopped loving photography, taking his camera and his iPhone everywhere, snapping in the street, feasting on London’s sights and people. This search, bringing him to the beauty and troubles of marginalised communities, was informed in part by growing up gay in Iran. Since the 1979 revolution — when Shahablou was 15 — homosexuality has been illegal and punishable by death.

“He told me about growing up in Iran and becoming aware of [his] difference, and particularly when he was in prison — he was aware he had to be really careful,” said Gleeson. This was particularly the case because of what happened there. Shahablou was jailed for over two years in the 1980s for being a member of a dissident group.

More than two decades later, in 2011, Shahablou arrived in London. By this time, “he had a serious lack of self-confidence,” said Gleeson, but “he realised he could actually be true to himself.” He spent time in Soho and met LGBT people through his photography. One of them was the poet, author, and trans advocate Roz Kaveney, whom he photographed in 2016 for an Amnesty International exhibition of LGBT people.

“He was an empathic photographer,” Kaveney told BuzzFeed News. “He was very sensitive and good at picking up on one’s issues.” Years of illness had left her with a massive surgical hernia. She said: "Shahin was very much about the quality of the shot in terms of what I’d be comfortable with. That’s an important aspect of queer portrait photography: respect for difference.”

The author Elizabeth Cook, who knew Shahablou through friends, was at that exhibition in Bethnal Green, east London. “There were two beautiful photographs of Roz [Kaveney] by Shahin — really extraordinary," she said. "I’ve known Roz for more than 40 years and there was a depth to the photographs; an insight into something that Roz doesn’t deliberately show in her being. They were really profound and moving.”

“He was such a dear man,” said Cook. “There was something quite beautiful about his nature — clear and pure-hearted. Innocent, in a good way. A great gentleness.”

It was these qualities that drew Kevin Lismore to him in his final months. On their first date, Shahablou arrived with a bouquet of flowers. “He was very romantic. And he really liked telling me stories about his life and asking me for stories about mine. My stories always paled in comparison.”

When reports of the coronavirus hit, Lismore said Shahablou was very frightened. He had mild asthma and a leaky heart valve. He had had a cough since December, which developed into a chest infection in January. In March he was hospitalised and then discharged. Gleeson thinks he was not tested for the coronavirus, despite his symptoms. A few days later, an ambulance was called and from March 27, Shahablou was in intensive care on a ventilator.

“Every day I rang and just hoped and deluded myself that he would pull through,” said Gleeson.

Shahin Shahablou died on Wednesday, April 15.

“I had to tell his family,” said Gleeson. As he talked about Shahablou, Gleeson recalled the conversations he used to have with him, when life in London had become difficult, with work drying up, money tight, and problems with his housing. Gleeson used to ask his best friend why he didn’t return to Iran, where he could live in a nice house with his sisters. But there was something more fundamental than material comfort that Shahablou needed: to be himself.

“However bad things get,” he would tell Gleeson, “I’d still rather be here.”

UPDATE

This piece has been amended following publication due to sensitivity issues raised by an interviewee.

Comments sidebar

7 comments·