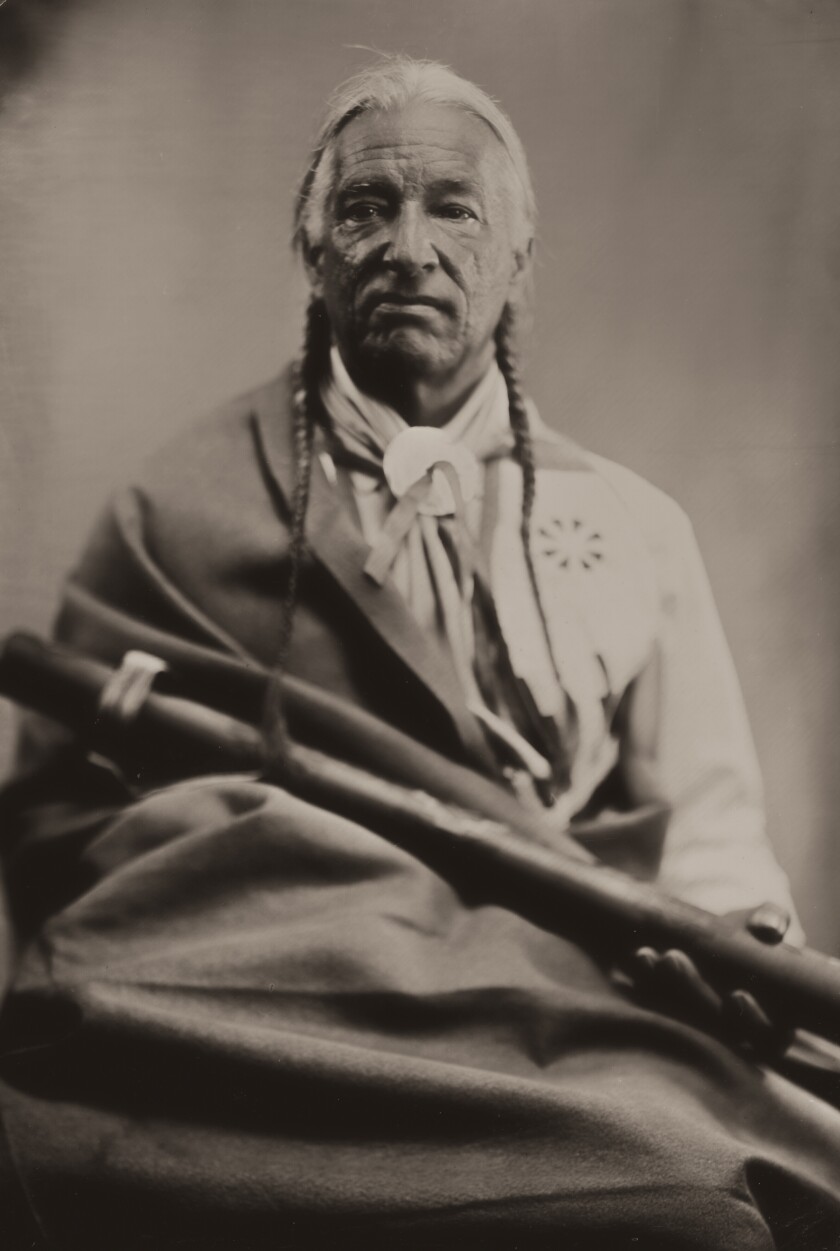

FORT YATES, N.D. — Kevin Locke played an important role in keeping alive the lost art of the Native American hoop dance. He also was an accomplished flute player, storyteller and educator who was described as a cultural ambassador.

Locke died unexpectedly on Saturday, Oct. 1, of what his son described as a “massive asthma attack” in announcing the death on Facebook . He was 68.

“My dad was like superman, clean diet, didn't smoke, only drank water, ran every day, always confident, never doubted himself, '' Ohiyesa Locke wrote in a Facebook post. “ I always knew he was going to be with me for a long time,” adding that his father “died a legend.”

Through his dancing, music and stories, Locke’s goal was to “empower today’s youth in culture and to raise awareness of the Oneness we share as human beings,” he said on his website .

“All the people have the same impulses, spirit and goals,” he told Indian Country Today in 2012. “Through my music and dance, I want to create a positive awareness of oneness in humanity.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Since 1978, he had traveled to more than 90 countries to perform, often before groups of students, which he said accounted for 80% of his appearances. One of his international appearances was in 1992 at the Earth Summit's Global Forum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

He performed as recently as Sept. 30 at Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills.

Lock said his “special joy is working with children on the reservations to ensure the survival and growth of indigenous culture.”

Born in southern California of Lakota and Anishinabe ancestry, Locke moved with his family to Standing Rock Indian Reservation at the age of 5. As an adult, he resided on the reservation in Wakpala, S.D.

In Lakota, Locke’s name was Tokaheya Inijin, meaning, “First to Rise.”

His lineage included a great-great grandfather, Little Crow, who was a leader of the 1862 Dakota Uprising in Minnesota. A great-grandfather, Bishop Charles Edward Locke, presided over the funeral of President William McKinley in 1901.

His mother, Patricia Locke, an activist for American Indian rights, saw to it that Locke learned while growing up the traditional Lakota ways of his heritage. He began playing the flute when he found one in his mother’s home, repeatedly listening to recordings made of traditional players by a Library of Congress ethnomusicologist in the 1930s.

As an adult, Locke taught himself to speak Lakota, which he seldom heard as a youth. He served on the board of directors of the Lakota Language Consortium.

ADVERTISEMENT

His many awards included a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and a Bush Foundation fellowship.

Locke attended high school at the Institute of the American Indian in New Mexico, and graduated with a degree in education from the University of North Dakota and a master’s degree in education administration from the University of South Dakota.

He worked for a time as a school teacher and administrator, and was admitted to law school but quickly dropped out, finding his life’s work in educating through his dancing, music and storytelling.