Thirty miles northwest of Kerrville, the hills begin to roll over the Divide, a five- to fifteen-mile-wide ridge that dissects the watersheds for the Llano and Guadalupe rivers. Save for the steel or stone ranch gates along the area’s two-lane highways, leading to the homes of descendants of the families who first settled the area, there aren’t many reminders of history here; it’s bluestem grass and live oaks as far as the eye can see. But on one rise, a small stone structure usually does draw curiosity: a 1936 schoolhouse, where, on May 28, 2015, the Divide Independent School District was hosting a graduation ceremony for its eleven students.

“Well, we want to welcome all of you to the 2015 Divide School graduation and promotion ceremony,” said the superintendent, Bill Bacon, as a small crowd settled in on metal folding chairs. “We want you to know we have some great stars for you here tonight and a wonderful program.” He motioned to a preschooler to join him on the tiny wood stage. “This is Grady,” he said. “He has thoroughly entertained us with stories about bad guys who are really good and imaginary heroes who almost die.”

Bacon went on to introduce the other preschoolers: Dax, who was so shy he wouldn’t open his eyes onstage; Savannah, who liked to sing “Five Little Monkeys”; and Savannah’s twin brother, Caden, who was known at school for giving the girls imaginary flowers. Masyn, another preschooler, had been unable to attend the ceremony, noted the superintendent. Then he presented the other students: Grady’s brother, Cody, was a second grader who obsessively watched the Weather Channel and always announced when it was about to rain; he was also the school’s current-events reporter, the first to offer details on a person hit by a truck or struck by lightning. Kameryn, now graduating the fourth grade, had legs so long she was beginning to run like a deer, just like the fifth graders, twins Eimy and Sofia. Sixth grader Caroline, Bacon’s own daughter, could take charge of any situation, such as when she’d answered the phone while the secretary was on maternity leave. And third grader Lidia had matured into a girl whose favorite subject was English, even though when she’d first enrolled she had been a scared, Spanish-speaking preschooler who would stop crying only when Bacon held her. (“I held her for about a month,” said Bacon. “One of my arms is still longer than the other.”)

Other students had come and gone over the year, which was typical: the school district, the smallest in Texas by population, serves families whose fates are inextricably tied to the land. Children of ranch hands don’t always stay, and they are often replaced by new arrivals, so that when asked about enrollment, Bacon had to try to reconstruct the year. “Let’s see,” he said, closing his eyes, “we started with eight, then we had nine, then eleven, then back to nine, then ten, then back to eight, then back to eleven.”

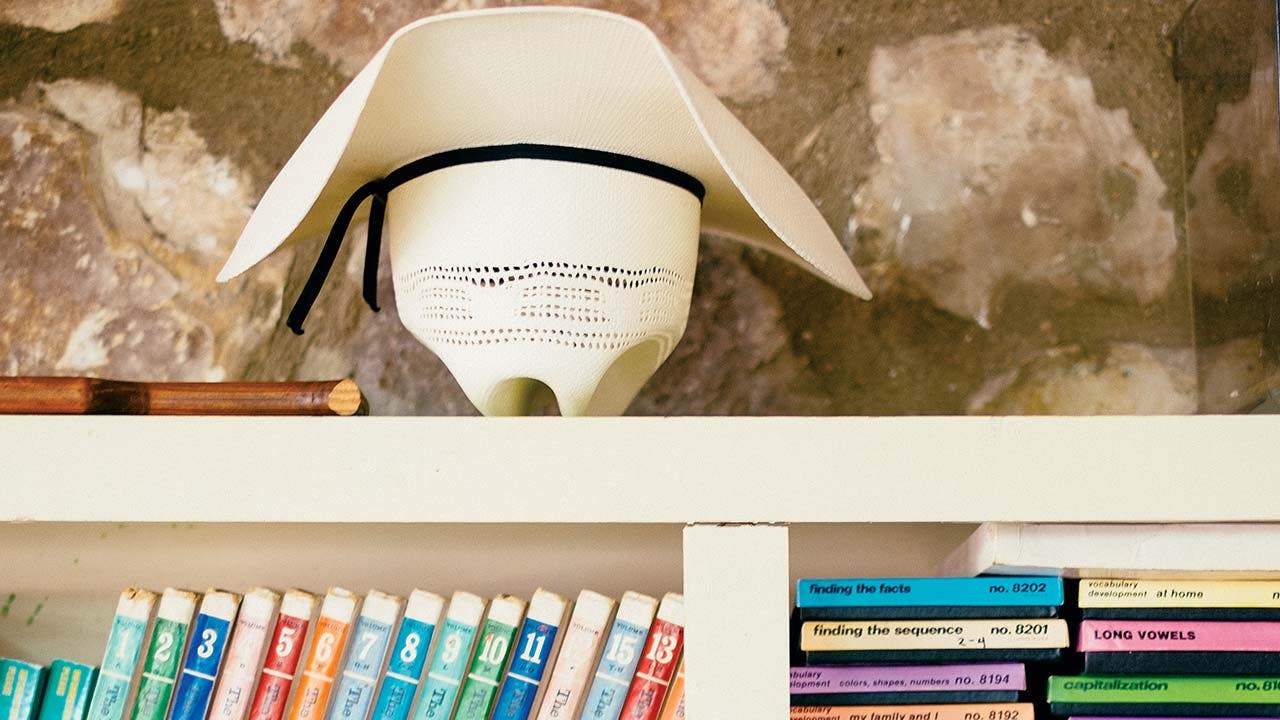

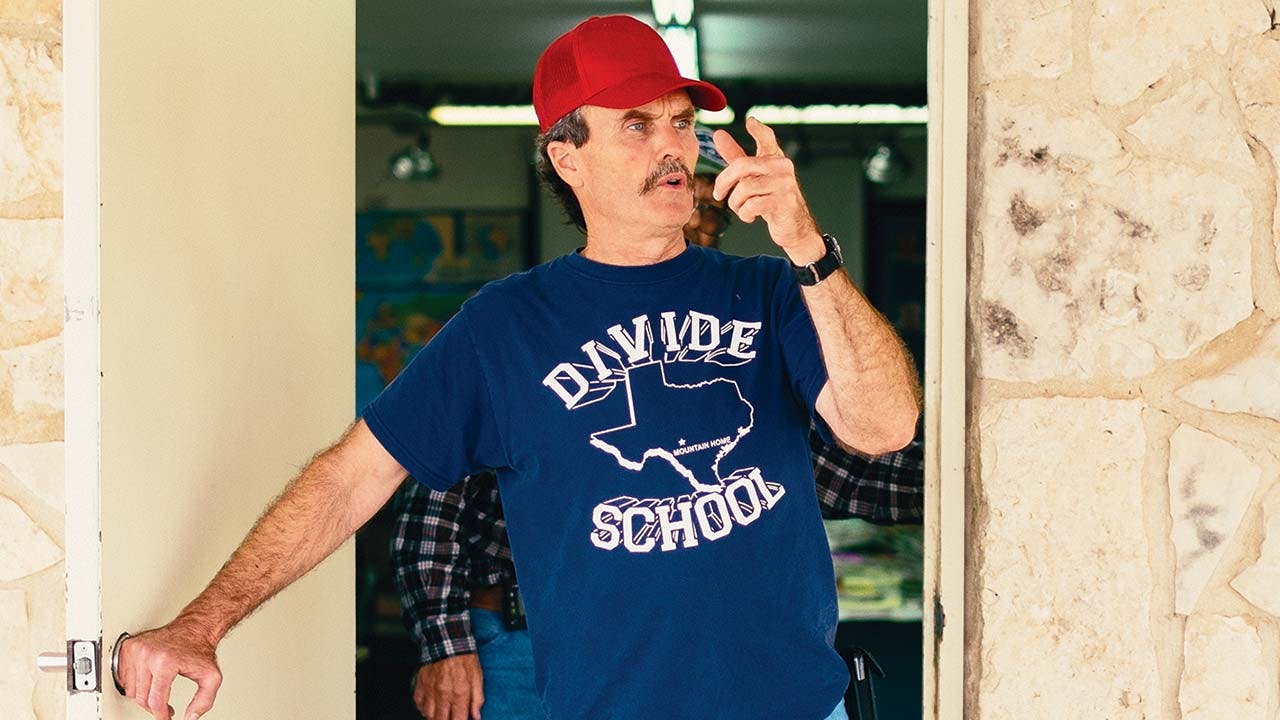

Bacon has run the Divide Independent School District, which consists of only elementary grades, for seventeen years. More specifically, he has been the superintendent, the principal, the third-to-sixth-grade teacher, the ESL instructor, the special-ed teacher, the repairman, the contractor, and the transportation director for the “bus,” which is actually a white limousine he purchased for a steal from a dealer in Dallas. He is not the only employee—there are four others, including two pre-K teacher’s aides, a kindergarten teacher who also teaches first and second grade, and a secretary—but he is the most involved. He says exactly what he thinks, though you might wonder why he bothers, since he often wears his emotions on his face, changing expressions with such frequency that it would take about fifty seconds to fill a gallery show titled “The Fifty Faces of Bill Bacon.” He is tall and skinny, with a graying mustache in the shape of a horseshoe, and when he’s talking, he hooks his thumbs in the pockets of his starched Wranglers. He keeps his cellphone in a belt holster. It almost goes without saying that on most days he wears a white straw hat to school, which sits on his desk while he’s in the classroom.

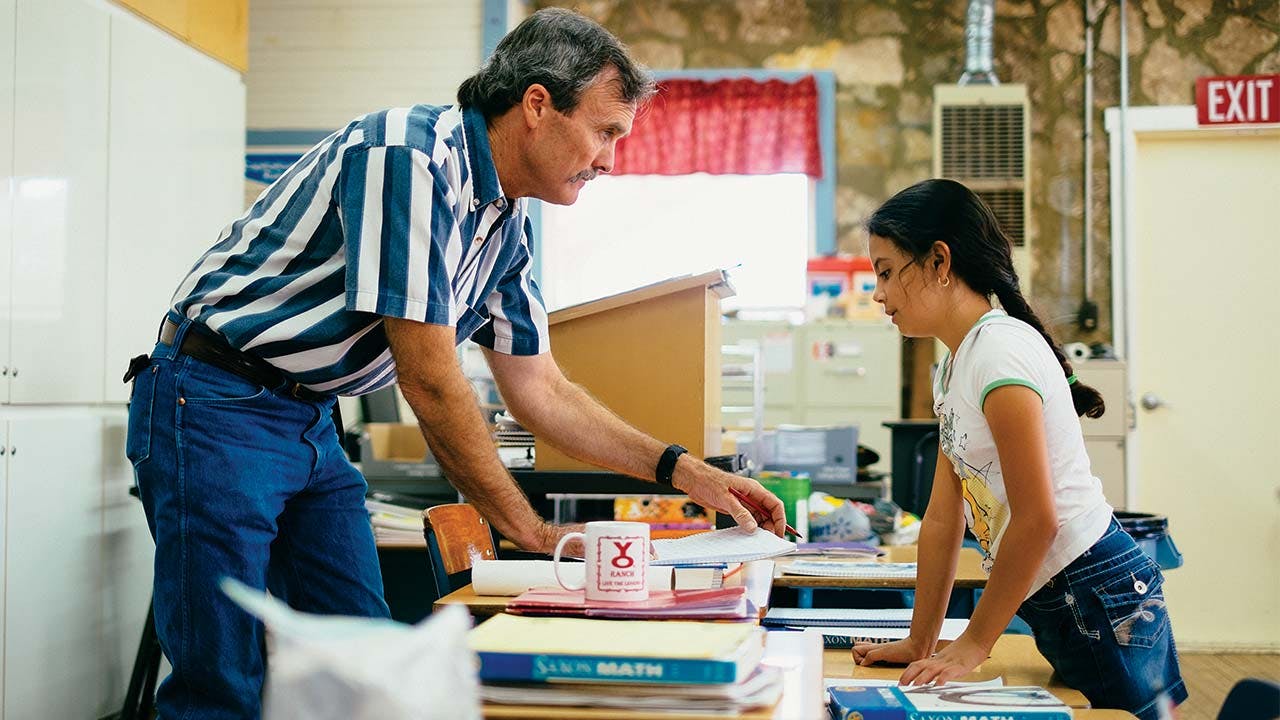

Bacon shares the values of the area ranchers and their hands, stressing hard work and pride in a job well done. He’s long on praise, especially if a student is exerting effort (“Oh, that’s a good sentence,” he’ll say. “I like that sentence right there”). He’s not above teaching practical problem-solving, as he did one day when he asked the upper grades to replace a doorknob, and like all good teachers, he draws on ideas that his kids can relate to, whether that’s in mnemonic devices (“She’s a pistil-packin’ mama” to remember the female part of the plant) or math word problems (“If sweet feed costs fifty cents . . .”). He’s also big on manners. Early in the school year, he asked a second-grade arrival from Kentucky if she was done with her work, and she turned her paper toward him to show that she was. He raised his eyebrows, then whispered with a wink, “It would have been just as easy to say, ‘Yes, sir.’ ”

As other, bigger districts in the state face the unwieldy challenges that come with managing more students and resources—superintendent problems in Dallas, budget woes in Austin, charter school debates in Houston—Bacon is mindful that he oversees one of the only schools of its kind in the country. Yet his job requires the very same commitment and creativity. Around ten-thirty one morning the first week of class, he’d noticed that Caroline couldn’t seem to keep her legs from bouncing and that Eimy and Sofia were starting to slump like melting snowmen. “Second row,” he called out, “take a lap.” The three girls darted out the side door, their long hair waving as they disappeared past Bacon’s border collie, Ace, and into a back field, hopping over cow patties.

The Divide School isn’t technically a one-room schoolhouse. People sometimes refer to it that way because the upper grades hold their classes in the district’s original single-room building, a 79-year-old stone structure whose windows are currently decorated with red bandanna-print valances. Local rancher Fred “Barney” Klein donated the property and collected the money to build the school soon after the state constructed Texas Highway 41 through this section of West Kerr County. (Klein’s great-grandsons Grady and Cody are the fourth generation in the family to attend.) But since opening, its superintendents have undertaken multiple renovations, installing electricity, cutting the single room in two, adding a small library and a reception area, and erecting a separate building for pre-K out back. A few years ago, when the student population exploded to thirty, Bacon wrangled a few used portable buildings. Now that enrollment is back down, following a decrease in local ranch employment, one of them hosts the younger grades and the rest are mostly used for storage.

This fall, he expects to end up with around twenty students. He always wishes he could get more. Often, he’ll say things like, “What’s breaking my heart is, I wish I had another sixth grader to be with my daughter and another second grader to be with Cody.” No doubt, some part of his desire is financial. Divide receives a small guaranteed amount of money from the state, but like all schools, it also receives a crucial portion of money per pupil. And there will always be unforeseen events to contend with, like when the ceiling needed replacing one summer or the alternator on the limo burned out last fall.

The community is always eager to help, of course. The Divide Parent-Teacher Organization raises money by hosting a wild-game dinner each fall, and if Bacon can’t fix a problem himself (as he did the ceiling fan and the light fixtures), he’ll find a volunteer. (He asked the photographer for this story, Jay B. Sauceda, who visited the school throughout the year, if he had a knack with alternators.) In December, when the school was left without a music teacher to produce the Christmas play—the one who had flown in from Alaska the previous three years couldn’t make it—Bacon put the upper-grade girls in charge. Caroline wrote and directed the play, Eimy composed a song to the melody of “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” and Kameryn choreographed a number from the movie Frozen that incorporated red-and-white-striped canes and multiple gymnastic feats.

Bacon wasn’t always a teacher. He used to own a roofing company with his brother in Kerrville, a healthy business until a storm ravaged the area and resulted, a year later, in new roofs for everyone—and no more repairs for the brothers to do. Bacon, who had a finance degree, considered becoming an insurance adjuster, but it didn’t fit his personality. He liked helping people in unexpected ways. “All the time I was in the roofing business, I was a banker, a marriage counselor, a bail bondsman,” he said. He wondered if he could make a difference in others’ lives if he caught them before they went into the workforce. So at age 31 he went back to school and got a teaching certificate. He started out in special education in Hunt, slowly taking on more responsibilities, until he was asked to oversee the Divide School, in 1998. “I lived at the school—I put in the hours,” he said. “It’s a lifestyle, and for me, you know, it’s kind of like my own business. You take a guy who works for himself, a guy who owns his own store: he doesn’t work eight to five. When something needs to be done, he does it.” If the urinal in the boys’ bathroom breaks, Bacon knows what he’s doing that weekend.

The closest elementary schools are at least thirty miles in any direction: Ingram and Harper to the east and northeast, Leakey to the southwest, Junction to the north. Still, Bacon has felt the threat of closure. Back in the early aughts, during a winter break, he was at school when he received a worrisome call. “The phone rang, and this old boy said, ‘Mr. Bacon?’ I said, ‘Yessir.’ He said, ‘My name is Will Counihan, and I’m with the state comptroller’s office.’ Well, it’s never good when you get a phone call from the comptroller’s office; they’re not wanting to chitchat. There was a problem. He said, ‘We’re going to come to your school with a team of twelve to fourteen people, and we’re going to look at every aspect of your district: the finances, the special education, the education services, the bilingual program, the food services, the transportation, and your federal programs.’ Then they asked, ‘Do you have any questions?’ ” Bacon’s voice squeaked as he continued, trying to contain the laughter creeping up his throat. “I said, ‘Yes. Why am I so blessed?’ ”

When his visitors arrived—in the end, the group had been reduced to seven—Bacon sat them at a half-moon table and answered their questions with rapid-fire delivery. “They said, ‘We want to talk to your principal,’ and I said, ‘Well, I am the principal.’ ‘We want to talk to your superintendent.’ ‘Well, I am the superintendent.’ ‘Where’s your maintenance director?’ ‘Well, I am the maintenance director.’ ” His inquisitors were so impressed with him that they left the school open. “ ‘Every single person on our team was planning on closing this school,’ Mr. Counihan told me, ‘and the consensus was—and it was one hundred percent—that the state of Texas would be better served consolidating you with another district. But after being here, not one person is in favor of that.’ ” Bacon smiled at the memory. “Of course, that was music to my ears,” he said. He thought about it for a second. “The visit could have been a curse, but as it turns out, it was the most wonderful thing that could have happened to me.”

On the afternoon of the last day of the school year, Bacon was about to print out the yearbooks for that night’s graduation ceremony when the printer ran out of toner. He called up the local Documation store, a thirty-minute drive away in Kerrville, and crossed his fingers that the toner would be delivered before six o’clock. Then he let the matter go. It was Splash Day, after all, and the kids were already filling water balloons like infantry readying for battle. When his 84-year-old mother, “Mom Bacon” (pronounced as one word), arrived, wearing a long denim skirt with the state of Texas embroidered on it, he excused himself. He needed to change into his trunks.

Under an open-air roof that sometimes serves as the gym area, students filled kiddie pools and moved a cooler crammed with water balloons into position until Bacon emerged from the side door in shorts and a 2015 Divide School T-shirt. He was holding a water squirter. The children squealed, then attacked. On a small hill nearby, Missie Dreiss, the mother of Grady and Cody, looked on, ducking occasionally to avoid the line of fire. “My dream is for the boys to take over the ranch,” she said as the kids launched their water bombs. (“Grady, I’m on your teeeaam!” one child screamed.) “Grady wants to be a pediatric doctor or a cardiologist, and Cody wants to be a firefighter and fly helicopters for an air evac. Usually kids go to college and come back. Most of these families are in ranching, so they could come back after they retire or sooner than that.”

She can’t imagine how her kids would handle themselves in a city. “We’ve never had a neighbor,” she said. (“Get him, Kameryn!”) “The worst thing is a snake, not a car. You have to learn your town voice too; you can’t just go hollering. And learning to cross the street—that’s a big deal.

“My husband and I always say we hope we won’t be eighty years old trying to run the ranch, so we’re teaching the boys the business. They have forty hens, and they’re responsible for the feed and water; they put the chickens up at night. We sell the eggs to Bible study and teachers and put the money into their accounts. We’re trying to get them to choose the feed. Hopefully they’ll get to make their mistakes now, as children.” Suddenly she looked excited about something in the distance. “Look, here comes the printer guy!”

A cloud of dust trailed a white Documation minivan that had taken on the glow of an emergency vehicle. That evening, the kids would all receive their certificates, as well as medals. Bacon, reminiscing about the year, would pull forward the only graduate who was leaving. “I’m going to tell you, Caroline, we’re going to miss you next year,” he would say as his daughter approached the stage, her face wet with tears. She was headed off to middle school in Harper, forty miles away, where Bacon’s wife, Cindy, is a teacher. “Don’t worry, we’re going to write you letters. We’re going to get that boarding school’s address in Switzerland.”

But right now Bacon needed to focus. As the water balloon fight wound down, three children new to the area had arrived at Divide with their mother, enrollment papers in hand. The two boys, both kindergarten age, didn’t seem fazed by their surroundings; they were too busy swinging from a railing by the back door. Their sister, however, about eight years old, was wary, watching Bacon out of the corner of her eye. A new school, seemingly in the middle of nowhere—it was enough to give a kid pause.

Bacon walked out to meet them in dry clothes, and as he put his shoes on, the children gravitated toward him, hanging on to the school’s back-porch beams and spinning around. “What’s your favorite part of school?” he asked one boy, feeling him out.

“I like playing outside,” the boy answered.

“I like playing outside too,” his twin brother offered.

Bacon nodded intently.

“And you?” he asked the girl.

“I like math.”

“Oh, math,” he said, his eyes widening. The girl straightened her back proudly. “I bet you’re good at it too. Can you tell me what one hundred plus one hundred is?”

Comments