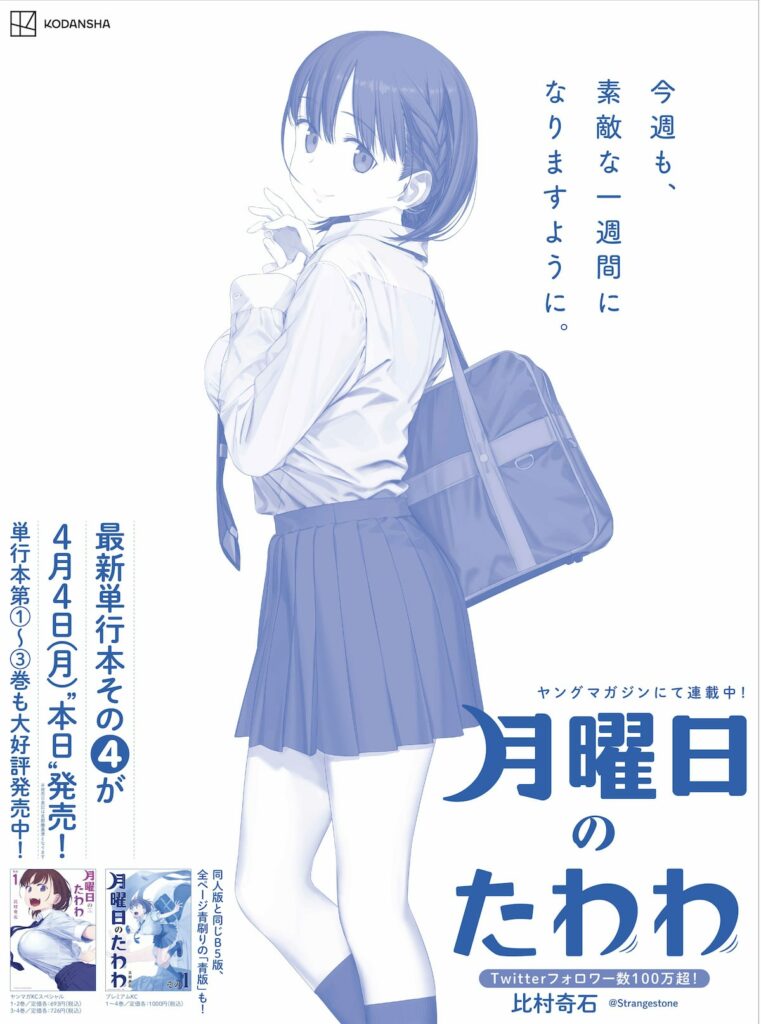

It’s not every day that discourse over a domestic advertisement takes on international precedence. On the 11th, the New York-based headquarters of the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (known as UN Women for short) issued a strongly worded letter to major Japanese newspaper The Nikkei over a full-page advertisement the latter had run on the 4th. The ad in question features the main character from Himura Kiseki’s Getsuyoubi no Tawawa in her high school uniform, and promotes the 4th volume of the web comic’s manga adaptation.

Since the character first appeared in February 2015, the character in question has become a mainstay of the ecchi (sexualized) manga ecosystem, whether in her original weekly single-image form, or more recent anime and manga adaptations. While the main content of the ad is not explicit, it still clearly portrays a sexualized underage character; debate over the appropriateness of the advertisement ensued online. In its letter of objection, UN Women informed The Nikkei that the advertisement was “unacceptable.”

For The Nikkei, Monday Blues

In the world of Japanese advertisements, this particular ad might not always have made such waves. Sexualized manga imagery can still be seen on billboards around Tokyo, on the subway, or even notably on a since-removed controversial Red Cross campaign poster; comparatively, this ad seems merely suggestive, rather than graphic. For UN Women, however, the nature of the publishing entity was reason enough for scrutiny. The Nikkei is, in fact, a partner of the UN Women Japan branch. Specifically, the newspaper participates in UN Women’s “Unstereotype Alliance,” which devotes itself to ridding society of harmful stereotypical images. From UN Women’s perspective, the publishing of this ad represents a violation of that partnership.

An Issue of Contradiction

“Stereotypes regarding women and girls are a major factor in preventing the realization of gender equality,” UN Women Japan chief Ishikawa Kae told HuffingtonPost.jp in a recent interview on the issue of the Getsuyoubi no Tawawa ad. [1] “Because advertisements have a major influence on the formation of societal norms… the advertisement in question is a violation of the [The NIkkei‘s] agreements to participate in the Unstereotype Alliance.”

For UN Women, the issue at the heart of the ad was the continued sexualization of high school-aged female characters for the benefit of an older male readership. Chief Ishikawa had more to say on this topic:

“A manga advertisement that portrays an underaged woman in a school uniform in a sexualized manner plays a part in strengthening the stereotype that ‘high schools girls should be this way.’ It also holds the danger that it can encourage men to sexually exploit underage women. UN Women is opposed to the publishing of such ads. It goes against the memoranda exchanged between [The Nikkei] and UN Women.”

UN Women Japan is hoping that The Nikkei will explain its conduct.

A Problem Not Limited to 2D

It is indeed true that female high school students remain highly sexualized in popular media throughout Japan. JK (joshi kosei, “high school girl”) cafes featuring high school students in their school uniforms are still popular with some adult men; Akihabara still plays host to “JK Alley,” a street known as a popular pick-up spot for men looking to pay high school girls for accompaniment. PapaKatsu, a word describing the finding of older sugar daddies, is still in the vernacular. Love hotels feature high school uniform dress-up, while innumerable ecchi anime focus on high school or even middle school settings.

Manga Mogura RE on Twitter: “”Getsuyoubi no Tawawa” vol 4 regular & blue ink edition by Himura Kiseki pic.twitter.com/H6lJIs192j / Twitter”

“Getsuyoubi no Tawawa” vol 4 regular & blue ink edition by Himura Kiseki pic.twitter.com/H6lJIs192j

The manga in question, Getsuyoubi no Tawawa, is a fantasy fulfillment story about a middle-aged salaryman who befriends a manga-proportioned high school girl. (The focus character is nicknamed “Ai-chan” as a pun on her I-Cup bra size.) While the manga purports to portray the way society focuses on the female body and associated body image issues girls face, it remains unabashedly sexualized and exaggerated.

The main ad is actually comparatively reserved when put next to much of the art from Getsuyoubi no Tawawa itself. Meanwhile, an image of a manga volume being advertised in the bottom left corner of the ad better exemplifies the exaggerated art the series is known for. Online reactions to the initial ad in the April 4th morning edition of The NIkkei were heated; HuffPo JP reported some of these reactions:

“There are more than a few people tired of seeing a full-page national ad like this.” “This ad must make fathers with daughters worried, to say nothing of women themselves.”

In a separate article, HuffPo JP interviewed Associate Professor JIbu Renge of the Tokyo Institute of Technology about what made many perceive the advertisement as problematic. [2] She listed three main points:

- By publishing the ad on such a large platform, many people who have no desire to see its imagery were forced into doing so. The issue, in this case, is not the existence of the manga itself, but the audience to which it was advertised.

- The manga sexualizes underage high school characters. By publishing the ad, The Nikkei seems to be promoting adult men sexualizing high school girls.

- The Nikkei is contradicting its own work with UN Women in which it has claimed to stand against harmful gender stereotypes.

These three points seem to represent much of what is being argued online and elsewhere. As with most stories of this type, many have also risen to the advertisement’s defense, claiming they see nothing wrong in the advertisement itself.

Going Global

As of the writing of this article, #getsuyoubinotawawa is currently trending on Japanese-language Twitter. Debate is ensuing, with many defenders of the advertisement angry at UN “interference” in domestic Japanese affairs.

The above Twitter post gives an example of this type of backlash-to-backlash discourse:

“Are you stupid? This sort of thing is an everyday occurrence in Japan. For those who wonder what you should tell those on “the outside” about this, respond with “f*ck off.”

It’s in English, so it should get the message across. I’ve had about enough of this cancel culture. I’m not gonna be perturbed by what boring, helpless, shallow-thinking, superficial people say. #getsuyoubinotawawa.”

As the story continues to gain international attention, we can expect to see an increase in heated debate. More and more, it seems that domestic discussions of media representation – even from something like a newspaper ad – can easily escape the domestic sphere in which they first occur.

The threat of negative international attention seemed to be at play during the 2020 (2021) Tokyo Olympics; following a series of separate Olympic scandals, opening ceremonies director Kobayashi Kentaro was summarily removed from his position directly before the ceremony commenced, seemingly in order to head off international attention being given to a resurfaced holocaust joke from decades earlier.

Manga publishers like those who put out Getsuyoubi no Tawawa tend to be more insular in their reactivity (despite popularity overseas); The Nikkei, however, may feel pressured to respond as this story grows. However, it is worth noting that the initial negative reaction to the ad appearing in The Nikkei was a domestic one; the most important aspect of how the discussion of sexualized advertisement and the public portrayal of fictional underaged characters in Japan evolves will likely continue to be one undertaken in Japan, rather than in the halls of international organizations.

What To Read Next:

Japanese Schools Court Controversy with Draconian Hair Regulations

Sources:

[1] 金春喜。(2022年04月15日)。国連女性機関が『月曜日のたわわ』全面広告に抗議。「外の世界からの目を意識して」と日本事務所長。Huffingtonpost.jp.

[2] 金春喜。(2022年04月08日)。「月曜日のたわわ」全面広告を日経新聞が掲載。専門家が指摘する3つの問題点とは?。Huffingtonpost.jp.