In Supreme Court, Oklahoma seeks to reclaim criminal jurisdiction over tribal reservations

Oklahoma can prosecute non-Indians accused of crimes against Indians on tribal reservations because Congress has never explicitly barred states from exercising jurisdiction in such cases, Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor told the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday.

A state has “inherent authority to prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes in Indian country within its borders, unless Congress preempts that authority,” the attorney general said in written arguments to the high court.

“Neither the General Crimes Act nor any other federal law preempts a State’s authority to prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes against Indians in Indian country within state borders. Nor does a State’s exercise of prosecutorial authority over those crimes interfere with tribal or federal interests.”

O’Connor’s brief came in the case of a man whose convictions were overturned in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in McGirt v Oklahoma in 2020. The high court ruled that the Muscogee (Creek) reservation was never disestablished by Congress and that Jimcy McGirt, a Native American, was wrongly tried by the state for crimes committed on that reservation.

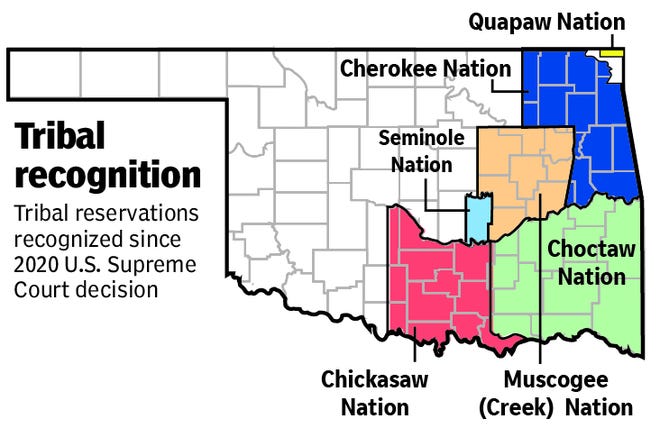

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has extended the McGirt decision to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Quapaw and Seminole reservations, meaning half the state’s population lives within a reservation.

More:Federal lawsuit challenges Oklahoma's right to tax Native Americans under McGirt ruling

Under federal law, crimes involving Native Americans on reservations must be prosecuted in federal or tribal courts. Tribes generally cannot prosecute non-Indians, except under circumstances provided for in the Violence Against Women Act, so non-Indians accused of crimes against Native Americans on reservations are typically prosecuted by U.S. attorneys.

The Supreme Court in January rejected appeals from O’Connor and Gov. Kevin Stitt to reverse the McGirt decision. However, justices agreed to consider whether the state has concurrent authority — with the federal government — to prosecute non-Indians accused of crimes against Native Americans on reservations.

Oral arguments in the case are expected to be held in April, with a decision likely coming this summer.

State appeals court earlier ruled Oklahoma does not have jurisdiction

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in a McGirt-related case last year that the state does not have concurrent jurisdiction in such cases.

“Absent any law, compact, or treaty allowing for jurisdiction in state, federal or tribal courts, federal and tribal governments have jurisdiction over crimes committed by or against Indians in Indian Country, and state jurisdiction over those crimes is preempted by federal law,” the court said.

The state court has rejected the state’s arguments in several similar cases, including the one now before the U.S. Supreme Court, which involves Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-Indian who was convicted in state court of child neglect and sentenced to 35 years in prison. The conviction was overturned in the wake of McGirt because the child is Native American and the crime occurred on the Cherokee reservation.

More:US Rep. Tom Cole says he doesn't want to 'overhype' prospects for McGirt funding

In its brief filed Monday, the state attorney general’s office said the state court’s decision was erroneous.

The attorney general dismissed arguments that federal laws allowing some states to exercise jurisdiction over Native American cases in Indian country were proof that Congress must explicitly authorize the prosecutions.

State-specific laws “do not implicitly preempt state power to prosecute non-Indians for crimes against Indians in Indian country,” the attorney general argued. “By their plain terms, those laws expand rather than limit state jurisdiction.”

The attorney general said the Supreme Court, in some civil cases, has balanced the interests of state, federal and tribal governments in reaching a decision.

“If the Court were to employ a similar approach here, it would clearly favor a State’s ability to prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes against Indians in Indian country,” the attorney general argued.

“No serious issues of tribal sovereignty are involved, because tribes lack the power to prosecute non-Indians. And as the federal government has recognized, States have a strong interest in prosecuting non-Indians who victimize Indians within their borders, and the exercise of that authority is unlikely to interfere with federal Interests.”

Attorneys for Castro-Huerta have a month to file a response to the state's brief.