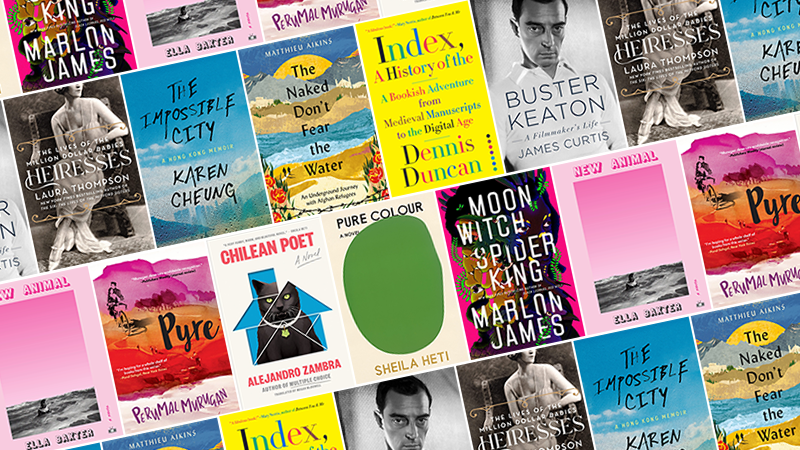

How Scholars Once Feared That the Book Index Would Destroy Reading

Dennis Duncan on the Hope, History and Necessity of All Those Numbers and Words

When I first began to teach English Literature at university, here is how a lesson would typically begin:

Me: Can everyone please turn to page 128 of Mrs Dalloway ?

Student A: What page is it in the Wordsworth edition?

Student B: What page is it in the Penguin edition?

Student C (holding up a book: mid-century; hardback; no jacket ): I don’t know what edition I’ve got—it’s my mum’s. What chapter is it?

After a minute or so, homing in via chapters and paragraphs, we would all be ready to analyze the same passage, only to go through the same process a couple of times more each class. About seven years ago, however, I noticed that something different was beginning to happen. I would still ask everyone to look at a particular extract from the novel; I would still, more in hope than expectation, give the page reference from the prescribed edition; a sea of hands would still go up immediately. But this time the question would be different: “What does the passage start with?”

Many of the students now were reading on digital devices—on Kindles, on iPads, sometimes on their phones—devices which did not use page numbers, but which came equipped with a search function. Historically, a special type of index, known as a concordance, would present an alphabetical list of every word in a given text—the works of Shakespeare, say, or the Bible—and all the places they appear. In my classroom I began to notice how the power of the concordance had been extended infinitely. Digitization had meant that the ability to search for a particular word or phrase was no longer tied to an individual work; now it was part of the eReader’s software platform. Whatever you’re reading, you can always hit Ctrl+F if you know what you’re looking for: “One of the triumphs of civilization, Peter Walsh thought.”

At the same time, the ubiquity of the search engine has given rise to a widespread anxiety that search has become a mentality, a mode of reading and learning that is supplanting the old modes, bringing with it a host of cataclysmic ills. It is, we are told, changing our brains, shortening our attention spans and eroding our capacity for memory. In literature, the novelist Will Self has declared that the serious novel is dead: we no longer have the patience for it. This is the Age of Distraction, and it is the search engine’s fault. A few years ago, an influential article in the Atlantic asked the question, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” and answered, strongly, in the affirmative.

But if we take the long view, this is nothing more than a recent outbreak of an old fever. The history of the index is full of such fears—that nobody will read properly any more, that extract reading will take the place of lengthier engagements with books, that we will ask new questions, perform new types of scholarship, forget the old ways of close reading, become deplorably, incurably inattentive—and all because of that infernal tool, the book index.

In the Restoration period, the pejorative index-raker was coined for writers who pad out their works with unnecessary quotations, while on the Continent Galileo grumbled at the armchair philosophers who, “in order to acquire a knowledge of natural effects, do not betake themselves to ships or crossbows or cannons, but retire into their studies and glance through an index or a table of contents to see whether Aristotle has said anything about them.” The book index: killing off experimental curiosity since the 17th century.

And yet, four centuries later, the sky has not fallen down. The index has endured, but so, alongside it, have readers, scholars, inventors. The way we read (the ways that we read, we should say, since everyone, every day, reads in many different modes: novels, newspapers, menus, street signs all require a different type of attention of us) might not be the same as 20 years ago. But neither were the ways we read then the same as those of, say, Virginia Woolf’s generation, or a family in the 18th century, or during the first flush of the printing press.

Reading does not have a Platonic ideal (and, for Plato, as we will find out, it was far from ideal). What we consider to be normal practice has always been a response to a complex of historical circumstances, with every shift in the social and technological environment producing an evolutionary effect in what ‘reading’ means. Not to evolve as readers—to wish that, as a society, we still read habitually with the same profound absorption as, say, the inhabitants of an 11th-century monastery, isolated from society with a library of half a dozen volumes—is as absurd as complaining that a butterfly is not beautiful enough. It is how it is because it has adapted perfectly to its environment.

This history of the book index, then, will do more than recount simply the successive refinements of this seemingly innocuous piece of text technology. It will show how the index responded to other shifts in the reading ecosystem—the rise of the novel, of the coffee-house periodical, of the scientific journal—and how readers, and reading, changed at these points. And it will show how the index often shouldered the blame for the anxieties of those invested in the modes of reading that went before. It will chart the relative fortunes of two types of index, the word index (also known as a concordance ) and the subject index, the first unfailingly faithful to the text it serves, the second balancing its allegiances between the work and the community of readers who will come to it. Both emerged at the same moment in the Middle Ages, with the subject index rising steadily in stature so that, by the mid 19th century, Lord Campbell could boast of having tried to make indexes mandatory by law in new books.

The concordance, by contrast, remained a specialist tool for much of the last millennium before roaring to prominence after the emergence of modern computing. But, for all our recent reliance on digital search tools, on search bars and Ctrl+F, I hope that this book will show that there is still life—exactly that: life—in the old back-of-book subject index, compiled by indexers who are very much alive. With this in mind, and before we start in earnest, two examples will illustrate the distinction I have been attempting to draw.

The way we read might not be the same as 20 years ago. But neither were the ways we read then the same as those of, say, Virginia Woolf’s generation.In March 1543, Henry VIII’s religious authorities raided the home of John Marbeck, a chorister at St George’s Chapel in Windsor. Marbeck was accused of having copied out a religious tract by the French theologian John Calvin. In doing so, he had broken a recent law against heresy. The penalty was death by burning. A search of Marbeck’s house turned up evidence of further questionable activity, handwritten sheets that testified to an immense and unusual literary endeavor. Marbeck had been compiling a concordance to the English Bible. He was about halfway through.

Only half a decade previously, the Bible in English had been contraband, its translators sent to the stake. Marbeck’s concordance looked suspicious, precisely the kind of unauthorized reading that had made the translation of the scriptures such a contentious matter. The banned tract had been his original crime, but now the concordance was, as Marbeck put it, “not one of the least matters . . . to aggrauate the cause of my trouble.” He was taken to Marshalsea prison. It was likely that he would be executed.

In Marshalsea, Marbeck came under interrogation. The authorities were aware of a Calvinist sect in Windsor and saw Marbeck as a minor player, someone who might, under pressure, implicate others. For Marbeck this was a chance to acquit himself. With regard to the Calvinist tract, the statute forbidding it had only come into law four years earlier in 1539. But, protested Marbeck, he had made his copy before that. A simple defence.

The concordance posed a more serious problem. While ardently religious and industriously literate, Marbeck was also an autodidact. He had not been schooled deeply in Latin, but had learned just enough to navigate a Latin concordance, plundering it for its locators—the instances of each word—then looking these up in an English Bible and thereby building his English concordance. To Marbeck’s interrogators it seemed unthinkable that he could be working between two languages without being fluent in both. Surely a theological project like this could not be undertaken by a single amateur, devoted but untutored. Surely Marbeck was merely the copyist, taking direction from others, an underling in a broader faction. Surely there must be some coded intent in the concordance, some heretical selection or retranslation of its terms, rather than the guileless, procedural conversion Marbeck claimed.

An account of the inquisition, probably taken first hand from Marbeck, appears in John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments (1570). The accuser here is Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester:

What helpers hadest thou in settyng forth thy boke?

Forsoth my lord, quoth he, none.

None, quoth the Bishop how can that be? It is not possible that thou shouldest do it without helpe.

Truly my lord, quoth he, I can not tell in what part your Lordshyp doth take it, but how soever it be, I wil not deny but I dyd it without the helpe of any man saue God alone.12

The questioning continues in this vein, with others joining in the attack:

Then said the Bishop of Salisbury, whose help hadst thou in setting forth this booke?

Truly my Lord, quoth he, no helpe at all.

How couldest thou, quoth the bishop, inuent such a booke, or know what a Concordance ment, without an instructer.

Amidst the disbelief there is also a curious type of admiration. When the Bishop of Salisbury produces some sheets from the suspect concordance, one of the other inquisitors examines them and remarks, “This man has been better occupied than a great many of our priests.”

Now Marbeck plays his trump card. He asks the assembled bishops to set him a challenge. As they are all aware, the concordance had only got as far as the letter L before Marbeck was arrested and his papers confiscated. Therefore, if the inquisitors were to choose a series of words from later in the alphabet and Marbeck were to compile entries for them—alone in prison—he would thereby demonstrate that he was perfectly capable of working unabetted. The panel accept. Marbeck is given a list of terms to index, along with an English Bible, a Latin concordance, and materials to write with. By the next day, the task has been triumphantly completed.

Marbeck was pardoned, but the drafts of his concordance were destroyed. Still, innocent and undeterred, he began again, and seven years after his arrest he was able to bring the work uncontroversially into print. Nevertheless, Marbeck’s preface sounds a cautious note. He states that he has used “the moste allowed translation” so that no heretical doctrine might have slipped in that way. Furthermore, he declares that he has not “altered or added any Worde in the moste holy Bible”. Nothing added, altered, or retranslated. Marbeck would live for another four decades, an organist and composer whose life had been spared because his concordance was only, scrupulously, that: a complete list of words and their instances, with no interpretation and therefore no heresy.

By contrast, let us glance briefly at the back pages of a history book from the late 19th century. The work is by J. Horace Round, and its title is Feudal England. Much of Round’s study sets out to correct what he sees as scholarly errors made by Edward Augustus Freeman, Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford. Freeman emerges as Round’s bête noire, responsible, Round feels, for a significant wrong turn in the study of the medieval period. Over the course of 600 pages, however, this animosity is diffuse. Feudal England, after all, and not Edward Freeman, is the principal subject of the book. In the index, however, the gloves come off:

Freeman, Professor: unacquainted with the Inq. Com. Cant. 4; ignores the Northamptonshire geld-roll 149; confuses the Inquisitio geldi 149; his contemptuous criticism 150, 337, 385, 434, 454; when himself in error 151; his charge against the Conqueror 152, 573; on Hugh d’Envermeu 159; on Hereward 160–4; his ‘certain’ history 323, 433; his ‘undoubted history’ 162, 476; his ‘facts’ 436; on Hemings’ cartulary 169; on Mr. Waters 190; on the introduction of feudal tenures 227–31, 260, 267–72, 301, 306; on the knight’s fee 234; on Ranulf Flambard 228; on the evidence of Domesday 229–31; underrates feudal influence 247, 536–8; on scutage 268; overlooks the Worcester relief 308; influenced by words and names 317, 338; on Normans under Edward 318 sqq.; his bias 319, 394–7; on Richard’s castle 320 sqq.; confuses individuals 323–4, 386, 473; his assumptions 323; on the name Alfred 327; on the Sheriff Thorold 328–9; on the battle of Hastings 332 sqq.; his pedantry 334–9; his ‘palisade’ 340 sqq., 354, 370, 372, 387, 391, 401; misconstrues his Latin 343, 436; his use of Wace 344–7, 348, 352, 355, 375; on William of Malmesbury 346, 410–14, 440; his words suppressed 347, 393; on the Bayeux Tapestry 348–51; imagines facts 352, 370, 387, 432; his supposed accuracy 353, 354, 384, 436–7, 440, 446, 448; right as to the shield-wall 354–8; his guesses 359, 362, 366, 375, 378–9, 380, 387, 433–6, 456, 462; his theory of Harold’s defeat 360, 380–1; his confused views 364–5, 403, 439, 446, 448; his dramatic tendency 365–6; evades difficulties 373, 454; his treatment of authorities 376–7, 449–51; on the relief of Arques 384; misunderstands tactics 381–3, 387; on Walter Giffard 385–6; his failure 388; his special weakness 388, 391; his splendid narrative 389, 393; his Homeric power 391; on Harold and his Standard 403–4; on Wace 404–6, 409; on Regenbald 425; on Earl Ralk 428; on William Malet 430; on the Conqueror’s earldoms 439; his Domesday errors and confusion 151, 425, 436–7, 438, 445–8, 463; on ‘the Civic League’ 433–5; his wild dream 438; his special interest in Exeter 431; on legends 441; on Thierry 451, 458; his method 454–5; on Lisois 460; on Stigand 461; on Walter Tirel 476–7; on St. Hugh’s action [1197] 528; on the Winchester Assembly 535–8; distorts feudalism 537; on the king’s court 538; on Richard’s change of seal 540; necessity of criticising his work, xi., 353.14

One could hardly imagine a more comprehensive or devastating attack, and yet it is hard not to be amused by it—by its relentlessness, its obsessional intensity. It is difficult to see its scare quotes—”his ‘certain’ history . . . his ‘undoubted’ history . . . his ‘facts’”—without imagining Round speaking, delivering the index out loud, a livid sarcasm in his voice. This is the subject index in its most extreme form, as far from the concordance as it can get. Where Marbeck’s method was meticulously neutral, Round’s is the polar opposite, all personality, all interpretation. Where Marbeck’s concordance was thorough, Round’s index is partial. It would be fair to say that John Marbeck owed his life to the difference between a concordance and a subject index.

But Round’s index is a curio, a wild outlier. The good subject index, though inevitably imbued with the personality of its compiler—their insights and decisions—is far more discreet. As with acting, it is rarely a positive sign if the general viewer starts to notice the workings that have gone into the performance. The ideal index anticipates how a book will be read, how it will be used, and quietly, expertly provides a map for these purposes. Part of what will emerge from this story, I hope, will be a defence of the humble subject index, assailed by the concordance’s digital avatar, the search bar. The concordance and the subject index, as it happens, came into being at the same moment, perhaps even the same year. They have both been with us for nearly eight centuries. Both are vital still.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Index, A History of the by Dennis Duncan. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton. Copyright © 2022.