Bad debts and Korean blood: Japanese tabloids in a frenzy after Princess Mako’s wedding postponed

The abrupt announcement that the wedding was being put off came with little warning, and the decision was attributed to a lack of time to prepare and a desire to avoid overloading the imperial family’s schedule

Officially, the wedding scheduled for November between Japan’s Princess Mako and Kei Komuro has been delayed by more than one year because the couple had insufficient time to make all the necessary preparations and they did not want their celebrations to clash with the abdication of the emperor in 2019.

Unofficially, the Imperial Household Agency – the power behind Japan’s Chrysanthemum Throne – has stepped in after a rash of media reports alleging the mother of Komuro, a commoner who works as a paralegal, borrowed 4 million yen (US$36,700) from her former fiancée to cover her son’s education expenses and then declined to pay it back.

According to reports in the Japanese media, Komuro’s mother said she regarded the money as a “gift”.

- A new book on a Dutch mission in 1795 suggests that kowtowing was rewarded with the emperor’s favour, something denied to Britain’s ambassador when he refused

It is a clash of empires that reads like Game of Thrones. The year is 1793. The Qianlong emperor of the Great Qing Empire grants an audience to Lord Macartney, ambassador from Britain’s King George III, at his summer resort of Rehe, now Chengde, a few days’ travel northeast from Beijing. But Macartney refuses to kowtow.

As a result, British requests for improvements in trade relations are denied and Macartney’s party is hurried out of China, bearing a written rebuke to the king that concludes George must, “tremblingly obey and show no negligence”.

But in 1842 and again in 1860, the British use military force to compel the Qing to surrender the same benefits Macartney had sought to negotiate. The Qing must open several Chinese ports to year-round foreign residence and allow permanent British diplomatic representation in Beijing. The British also gain possession of a certain island off the Guangdong coast with an excellent harbour.

Other foreign powers claim similar benefits under “most favoured nation” treaty clauses. They all eat away at Qing authority until revolution brings an end to imperial rule in 1912.

If only Macartney had been less arrogant and had made a full obeisance to Qianlong, says this popular version of the story, history might have taken a very different course.

Various members of Macartney’s entourage published accounts of the trip, promoting the view that although they returned home empty-handed, they at least did so with their dignity intact, flattering themselves that they had shown the Manchus and their Chinese subjects who was boss.

Two years later, the members of a lesser-known Dutch embassy abandoned dignity altogether, grovelling until their hats came off, and yet they, too, returned home with nothing. Or so contends Travels in China, the account of the British embassy published by John Barrow, Macartney’s comptroller, in 1804, in which he spends 16 pages denigrating the Dutch.

If self-abasement earned the Dutch nothing, then surely responsibility for the failure of the British embassy could not be placed at Macartney’s feet.

But in The Last Embassy, a new review of previously untranslated accounts of the Dutch mission published in June, author Tonio Andrade, Chinese history professor at Emory University, in the United States, suggests the Dutch mission was, in fact, a great success, achieving precisely what it set out to.

It also claims that Macartney did bend the knee, but just the one – as he would have done before George III. What he would not do was “knock the head” – kou tou or kowtow to the Qianlong emperor – a formal obeisance that involved dropping to both knees three times, on each occasion bending forward to bring the forehead to the floor.

Macartney had made it clear that he was not prepared to show any greater respect to a foreign potentate than he would to his own king, but upon reaching the capital he compromised. He offered to kowtow to the Qianlong emperor if a mandarin of equal rank would similarly prostrate himself before a portrait of George III, brought specifically for the purpose. Eventually, the emperor accepted deference.

The Dutch, however, were ready to kowtow from the start. Andrade combines the accounts of three members of the Dutch embassy with observations from Chinese, Korean and Spanish sources for a present-tense account of lively immediacy. The Dutch reports are detailed and personal, and offer fresh material outlining much that the British never saw, from a back road north from Canton (Guangzhou) to the capital, to a tour of the emperor’s private apartments at the Beijing Summer Palace – an honour never before bestowed on any Europeans.

When he arrived in Canton from the Dutch East India Company colony of Batavia (Jakarta), the Dutch ambassador, Isaac Titsingh, had set himself to study the recent British embassy in as much detail as possible. What he read, and what he heard from missionaries, traders, Chinese merchants and mandarins alike, was that the difficulties of the British stemmed from Macartney’s failure to kowtow.

“Never”, French Jesuit missionary Jean-Baptiste-Joseph de Grammont would later write, “was an embassy deserving of better success […] And yet, strange to tell, never was there an embassy that succeeded so ill.”

Grammont was not entirely reliable as a source, and indeed was not present when Macartney met the Qianlong emperor. He gave Macartney’s failure to dress up as another reason for the embassy’s lack of success, in contrast to a British account that described the brilliance of Macartney’s costume. But Grammont does insist that the rituals were an issue, although he may just have been repeating gossip.

The British were suspicious of the Jesuits and particularly of those who were French, such as Grammont, and heirs to France’s historical enmity for England as well as to Catholic hatred for English Protestantism. Barrow accuses Grammont of influencing the Qianlong emperor against the British by whispering about military aggression in India.

The Dutch paid careful attention to what Grammont had to say, ordering so much new clothing that their Canton tailors had to hire new staff, and they used their limited budget to acquire gifts of a quantity and magnificence they hoped would match those of the British. They took instruction on how to perform the kowtow and practised it in front of local mandarins.

The British demands that Macartney made and his refusal to play by protocols – those were seen as a symptom of a deeper problem, which was that the British were seen as aggressive

Titsingh had twice served the Dutch East India Company in Japan and was on the point of retirement. He was a confirmed Japanophile, although sceptical about China. His deputy, Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest, on the other hand, was a Sinophile who had been in charge of the Dutch warehouses in Canton. He had proposed himself as ambassador.

In fact, the embassy was taking place only because Van Braam had received word from Changlin, the local viceroy, that it would please him to see European embassies congratulate the Qianlong emperor on completing his 60th year on the throne. Van Braam wrote to Batavia to advise that European competitors were sending embassies and the Dutch could not afford to be left out, but as Titsingh discovered on his arrival, only the Dutch would be travelling north.

Both of these men produced accounts of the journey, as did one Chrétien-Louis-Joseph de Guignes, who was hired as interpreter.

The local mandarins had objections as they had been taken in by foreigners before: de Guignes was French, not Dutch, and the embassy’s letter of introduction lacked the seal of the Prince of Orange, head of state. And they wanted no repeat of the Macartney debacle, with the sudden presentation of a list of trade requests. This must be a mission solely to offer congratulations, which the Dutch agreed it would be.

This is the point, according to Barrow, at which the Dutch embassy failed, giving up all rights to broach the subject of trade before it had even set off.

Once the emperor agreed to the Dutch proposal all local reservations were dropped. He had decided he wanted the Dutch in Beijing before Lunar New Year, which would mean their leaving at short notice and making rapid progress through the bitter northern winter.

There would be no time for appropriate gifts to arrive from Europe, but luckily there was the Canton shop of Scotsman Daniel Beale, a specialist in fine clockwork, whose inventory, Andrade tells us, contained “marvelous mechanisms of gold and silver that play music and perform scenes: fishermen casting rods, couples dancing, birds singing, scribes writing”, such as may still be seen in the Forbidden City’s Hall of Clocks and Watches today.

In order to arrive in Beijing in time the party would not be travelling in relative comfort by river and canal, but more directly on foot, by sedan chair or on horseback.

Andrade combines published reports and private diaries to provide an animated account full of grumpy detail, describing a relentless winter journey across some of China’s poorest provinces, which were unused to seeing the grand pass through.

There were blizzards, freezing winds and mountain passes to cross. The overworked porters and bearers were inadequately paid, or not paid at all, and so would abandon the Dutch without notice, or fail to arrive with their bedding before night fell at some forlorn hut.

“There’s no wine and no dinner for Christmas Eve,” Andrade writes, “which they spend in the township of Zhangqiao (張橋). They even lack underwear to change into and bedding to sleep on. Yet the officials escorting them seem to suffer no such privation. ‘We plainly saw,’ Van Braam notes, ‘that the hardships we suffered proceeded from a want of order, and from the inattention of the different Mandarins of the provinces. An incontrovertible proof of this fact is that the Mandarins, our conductors, who depended solely upon themselves, were in want of nothing.’”

Eventually they were promised smoother travel in carriages.

“The vehicles are like farm-carts,” writes Andrade, “the sort that a European peasant would use to haul onions to market: small, with solid wooden wheels and simple thick dowels for axles. Each one has a roof made of mats but is open in the front. They don’t even have benches – just straw spread at the bottom. In Europe, carriages have comfortable seats, glass windows, and springs to act as shock absorbers.”

De Guignes later realised that even Chinese high officials used such carts. This understanding that the Manchus and Chinese treated the visitors no worse than themselves became central to the positive views the Dutch and their French interpreter eventually shared when they wrote of their journey.

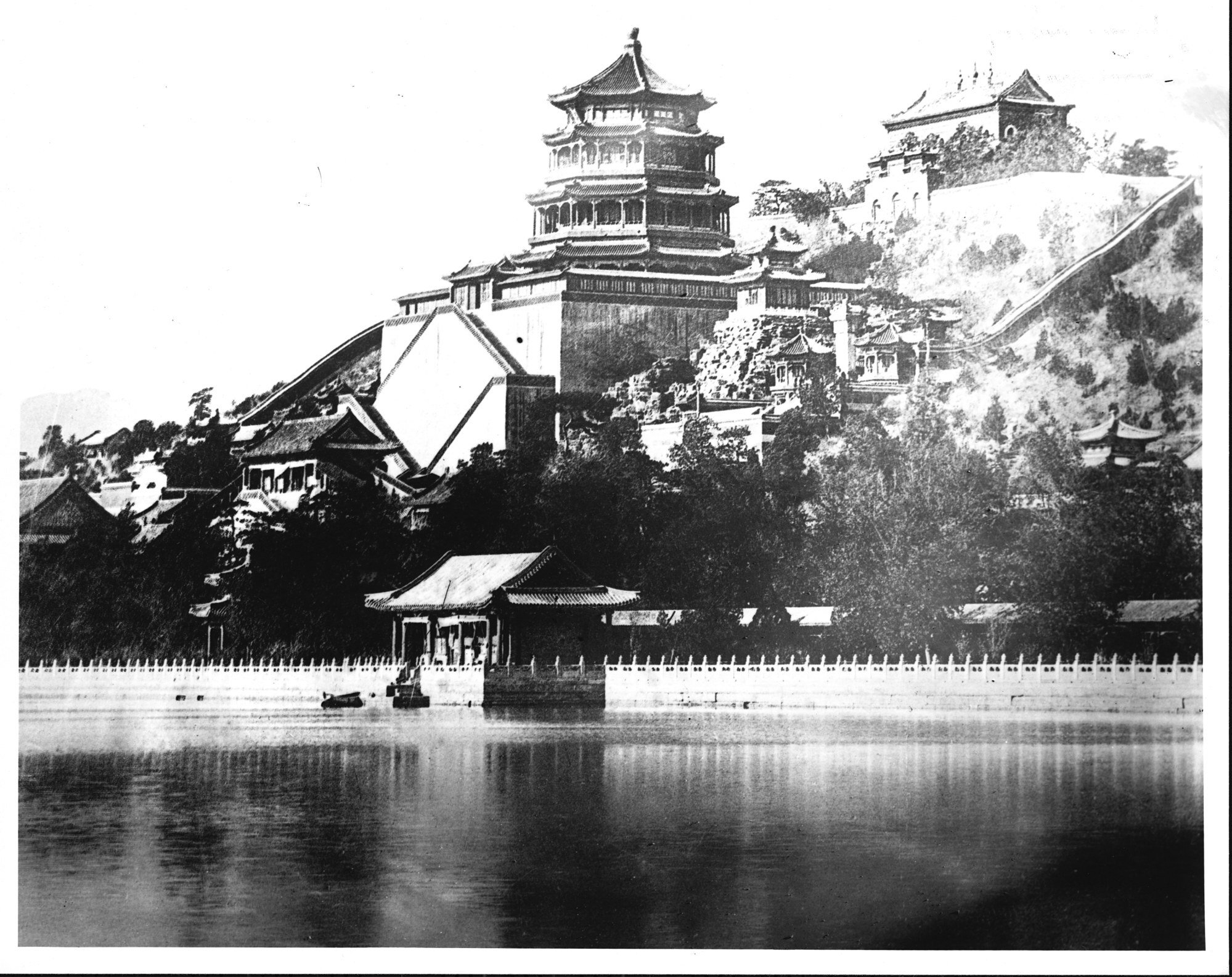

On a tour of the Summer Palace the Dutch would encounter one of Macartney’s luxurious well-sprung carriages on display, unused. But it would go up in flames when British and French forces torched the complex in 1860 – a retaliation for the torturing to death under a flag of truce of 18 envoys the Manchus themselves had requested.

The Dutch arrived a day early to find their accommodation not yet ready, and so spent a final miserable night outside the city walls before moving into spacious rooms honourably located within the capital’s inner enclosure, the Imperial City, and close to the Forbidden City itself. These lodgings were superior to those that had been provided to Macartney two years earlier.

They kowtowed each time they met the emperor, and each time they receive a message or a gift from him. They kowtowed to the emperor’s favourite, his notoriously corrupt prime minister, He Shen. On one occasion Van Braam’s hat fell off and the emperor was seen to laugh, which delighted the Dutch – they were making a connection. But this event is mentioned by Barrow with a sneer.

They were treated to entertainment and banquets in Beijing and at the nearby Summer Palace, which they found magnificent, although just as at the Forbidden City, there were hovels, dirt and decrepitude to be found, too. They froze during midwinter predawn gatherings because they declined to wear cloaks.

They wished to display the finery that they had been advised by the Jesuits the Manchus would want to see. In fact their exotic appearance made them part of the imperial entertainments for everyone else. The emperor was gracious, sending titbits from his own table, repulsive though these might sometimes have been to them.

Of the Jesuits they saw little. He Shen wanted no word to get out of the rough treatment the Dutch had received on their way north, and prevented contact.

The presents brought for the Qianlong emperor did not impress, as Andrade reveals in the contents of a memorandum from the Qing Grand Council.

“We find that the country of England presented, in all, six large instruments, whereas now the country of Holland merely presents one pair of musical clocks and four pairs of gold watches. The rest of the items, such as camlets, great cloth and other such things, is in quantity not even one or two tenths of what the country of England presented.”

But the emperor liked the Dutch regardless, and issued instructions that they were to be well looked after on their return journey via the Grand Canal and various rivers, the same route that had been taken by the returning British. They were indeed feasted and taken on tours such as Macartney never saw, being allowed more time for their passage. The mandarins continued to short-change them on accommodation during land transfers over watersheds, but the Dutch later claimed to have taken this in good part.

“Those people accommodate themselves to everything,” writes de Guignes. “Their carriages, for instance, which are truly like manure carts [tombereaux], are considered good by them, and their houses, too, they find excellent. What can one say against people who treat us as they treat themselves?

“Where the mandarins were of ill will was in taking the best things for themselves,” he continues, “and so, on our return, we often amused ourselves by taking for ourselves the best houses and boats, which had been intended for them. They didn’t complain at all and simply obtained other houses and boats for themselves.”

The embassy returned in triumph, having earned the Qianlong emperor’s goodwill. Viceroy Changlin, who held the administration of Canton trade in his hands, was pleased, too. And that was all they had desired.

That we have heard so much of the British view of China and so little of the Dutch one is in part a matter of historical accident.

Van Braam’s laudatory An Authentic Account of the Embassy of the Dutch East-India Company, to the Court of the Emperor of China, in the Years 1794 and 1795 appeared in two volumes in French, then Dutch, English and Danish around 1798. But 500 copies of the first volume in English were captured at sea by a French privateer.

A French publisher pirated it, republishing it in two volumes masquerading as the original, thus concentrating on the miserable northbound journey, and omitting the happier return portion and much else in praise of the Qianlong emperor and the Chinese. Being cheaper than the original it went on to outsell it, and was likely the source, knowingly or otherwise, of Barrow’s account of the Dutch embassy’s failure.

De Guignes’ Voyages à Peking, Manille et l’Île de France (1808) was never translated from French. Europe was then wracked by Napoleonic wars, and even while the Dutch were in transit the Dutch Republic had been replaced by a Napoleonic puppet state. The ambassador’s Isaac Titsingh in China (1794-1796) was not published until 2005, and even then only in Dutch.

So the more strident and widely distributed British voices won the day, particularly those of Barrow and of Macartney’s secretary, George Leonard Staunton, whose An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China (1797) drew on Macartney’s own diaries to deliver what it promised on the cover, and became part of the zeitgeist of the 19th century. Fanny Price is discovered reading it by her cousin in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814).

“People have said they didn’t gain anything so how can you say they were successful,” says Andrade on a video call from Georgia, “but if we want to gauge success we should gauge it from the perspective of the goals of the mission itself.”

Was it playing by Qing rules that made the difference?

“Partly yes, but also partly I think because the Dutch were not seen as an aggressive power like the British were. The British demands that Macartney made and his refusal to play by protocols – those were seen as a symptom of a deeper problem, which was that the British were seen as aggressive Western Ocean peoples.”

Like some other academics, Andrade argues that the problem lay in Macartney’s failure to speak the same language of diplomacy as the Qing. Diplomacy for them was about building relationships through ceremonial performances, whereas for the European nations there was a growing understanding of peer-to-peer exchanges between nations, and ones with concrete benefits.

“[The Qing] thought that diplomacy wasn’t all about negotiation,” says Andrade. “It was first and foremost about trying to create stability and harmony on Earth.”

“Stability” and “harmony” apparently even then meant “keeping us in power”. Just as the Chinese Communist Party does, the Qing knew that earlier dynasties had been toppled by peasant uprisings, and they feared the collusion of “hostile foreign forces”.

They were supposed to be awestruck by [the emperor’] incredible power and persona and fall naturally to their knees

As Professor Henrietta Harrison, of Pembroke College, Oxford, points out in a 2017 paper for The American Historical Review, the Qianlong emperor’s letters to George III did not mention the kowtow, nor did instructions to regional authorities. These were preoccupied instead with increasing military preparedness in case the British should become belligerent in the face of rejection.

As Andrade remarks, the Dutch had already been present in Asia for many years. They had been militarily defeated by both the Japanese and the rump Ming dynasty, even as the conquering Qing drove it south. They were in no position to cause the Qing trouble.

“It made sense for the Dutch to focus on the Sinocentric system that had worked so well for them for 150 years or so,” he says.

But there is little point in spending large sums on networking if it does not yield some practical benefit. Goodwill cannot be deposited in the bank, and nor did it prevent the vast outflow of silver to China in return for tea, porcelain and silk.

Macartney certainly believed that freer trade would benefit both parties and that what he was proposing was simply a matter of common sense. Even the Dutch were willing to talk trade if an opportunity arose, and they saw the Qianlong emperor’s liking for them as a gateway to future benefits.

In fact, the participants were all speaking the same language of diplomacy, but the Qing successfully avoided discussing any alterations to trade relations that might loosen their control or reduce the flow of silver directly into imperial household coffers – which is where most foreign trade taxes ended up, much to British annoyance.

Andrade concurs that self-interest was the motivation for both the British and the Dutch.

“It’s how you go about achieving that self-interest and what your overall goals are for the interaction. The Dutch intended to make the viceroy like them and to make good relations with the court, and I think they were spurred most importantly by a perceived sense of competition with the other Europeans. ‘We can’t be left out – there’s going to be a big party. We don’t want to be the only ones not invited.’”

There is another possible reason Macartney’s refusal to kowtow was not discussed in the Qianlong emperor’s letters.

“I think Macartney did kowtow,” says Harrison on a video call from Oxford.

She presents her arguments in a fascinating forthcoming book, The Perils of Interpreting, which looks at the consequences to the lives of one English and one Chinese interpreter of working for the British. She has been reviewing private correspondence between embassy members and their friends, and drafts of diary entries, with much crossing out, all suggesting the deliberate suppression of information.

“It’s clear that [Macartney] took an extremely limited number of people up to Chengde and that they were people over whom he had very tight control. And it’s also clear that there are two possible moments in this meeting when he might have kowtowed. One of them is when the emperor first arrived, and the other is when he went into the tent – the emperor’s yurt – to present him with his credentials in a gold box.”

It is clear that in the yurt he went down only on one knee in the pre-agreed ceremony, she says, but it is not at all clear what he did when the emperor first arrived.

“There are about 3,000 Qing officials standing in a three-rank circle,” says Harrison, “a very large circle. And they’re all standing there and they see Macartney going down. And George Leonard Staunton does not mention that moment in his account of the embassy at all. It’s just a blank.

“But Macartney’s nephew does say in his private writings they performed the prostration, and George Thomas Staunton [Staunton’s 13-year-old son, who was present as an interpreter] then wrote, ‘and then we bowed our heads to the ground’ and crossed it out in his diary. There’s definitely something very dodgy going on at that moment.”

Macartney was wearing the floor-length scarlet robes of the Order of the Bath, which perhaps conveniently obscured his movements.

Chengde was a kind of special cultural zone where different rules applied. It provided for a patronising celebration of multiculturalism where the rigid requirements of Chinese ritual were loosened to suit visitors from the vast Qing empire, of which China was just a part. Manchus went down on only one knee, and Tibetans, Mongols, Muslim peoples from newly conquered

, and other Inner Asia nomadic groups were also accommodated.“If you were going to be in that Chinese world, in the Forbidden City, then you were going to behave in these Chinese ways,” says Harrison. “But when you were out there in Chengde, there were different diplomatic rituals, which is not to say that people were not supposed to fall on their knees before the emperor. They were supposed to be awestruck by his incredible power and persona and fall naturally to their knees.”

According to the contemporary poet Guan Shiming, she writes, this is what happened with Macartney:

There is a distant land from across the sea that offers treasure,

Their hearts like wild deer, untamed and stubborn against the court rituals,

But the moment they enter the imperial presence both knees are on the ground.

The power of the Heavenly One can make all hearts submit.

Yet if the Qing accepted that Macartney had kowtowed, why did news circulate that he had refused? Perhaps, as is often the case, the Chinese were simply replaying foreigners’ own assumptions back to them, and this provided a convenient escape for Macartney, who would have needed to keep his kowtow secret. Back in the Chinese heartlands, when summoned to the Forbidden City to receive the Qianlong emperor’s letters, he declined to kowtow directly under the gaze of Confucian Chinese mandarins.

So did the Dutch’s open and repeated kowtowing, despised by other Europeans for the pressure it put on them to follow suit, benefit the Dutch?

Apparently not, although their timing was certainly poor. The Qianlong emperor abdicated later in 1795 to avoid reigning for longer than his illustrious grandfather, the Kangxi emperor, and this was the same year that Napoleon invaded the Dutch Republic and it ceased to exist, the Prince of Orange fleeing to England on a fishing boat. The Qianlong emperor remained effectively in charge until his death, in 1799, the same year that the Dutch East India Company was dissolved.

The Jiaqing emperor, his successor, was kept busy for several years dealing with rebellions, and he replaced his father’s hand-picked Manchu advisers with Chinese who had risen through the Confucian examination system. The court attitude to ceremony became in reality as hard-line as Macartney’s defenders claimed it was in the Qianlong emperor’s time. When a further British embassy arrived in 1816, its leader, Lord Amherst, declined to kowtow and was turned away without meeting the emperor.

The next high-level diplomatic encounter with Europeans would not come until the defeated Qing were forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing, in 1842, granting the British the opening up of trade they had sought. And there would be no kowtowing on that occasion.