Caught in a geopolitical tug of war between China and the US, many Chinese students at American universities are wrestling with a dilemma: should they stay, or go?

Several of these students – who declined to be named for fear of repercussions – said in interviews with the South China Morning Post they felt anxious about what they perceived as an increasingly hostile climate towards Chinese students in the US.

Trump’s toughened China policies could slow the influx of Chinese students into US schools.

This could reshape American society. Immigrants – of Chinese origin or otherwise – have been the backbone of the US economy, staffing everything from laundromats to advanced technological sectors.

But for Chinese students seeking a quality education, and their families, it’s also personal.

“A lot of students I talk to say they had hoped to stay and work in the US for several years, but have become resigned to the fact that that probably won’t be possible,” said Eric Fish, author of China’s Millennials: The Want Generation.

“In previous years, US schools have far and away been the top choice for these students, but lately they’ve been very quickly shifting their interest to Canadian and British universities.”

If potential Chinese arrivals already were having second thoughts about studying at US schools, their resistance to the idea hardened at reports that the Trump administration had debated banning visas for Chinese students over espionage concerns.

It “really freaked out a lot of the parents” at a top Shanghai education consultancy, Fish said.

Since the start of the US-China trade war last year, Washington has tightened visa restrictions for graduate researchers in hi-tech fields such as robotics, aviation and artificial intelligence. Several Chinese citizens working in these fields in the US have been arrested for allegedly spying on engineers and scientists.

A student who declined to be identified said he knew at least two Chinese masters’ students in the US who had opted to apply for PhD programs instead of trying to land a job.

The students see moving into the PhD track as a way to improve their chances of winning jobs or US citizenship.

“More students, including myself, have even considered returning to China as a plan B if we can’t find a job in the US, and some of them are searching for jobs in China simultaneously,” the student said.

42% of Chinese international students who took part in a 2018 survey conducted by Indiana’s Purdue University said their impressions of America had become more negative since they arrived in the US. When the survey was conducted in 2016, the number of students saying the same thing was 29%.

But the job market for new graduates on the other side of the globe is not much better, as Trump’s trade war begins to cause sweeping lay-offs and hiring freezes in China’s tech industry.

Zion Tam, an education consultant at Foundation Global Education in Hong Kong, said he expected students and families would pass on applying to US schools, “especially when they start seeing more student visa applications being rejected.”

He said his Hong Kong and mainland Chinese clients remained bullish on the US, because of the larger concentration of top-ranked schools there.

Other popular education destinations for Chinese students included Britain – for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge – as well as Canada, Australia and Switzerland, he said.

That said, the US is still considered a top destination for students and families who set their sights on the highest-ranked schools, said Julia Gooding, China director of international education at BE Education.

“If a Chinese student is aiming for the US News and World Report’s Top 30 universities, it will take more than a trade war to scare them off,” she said.

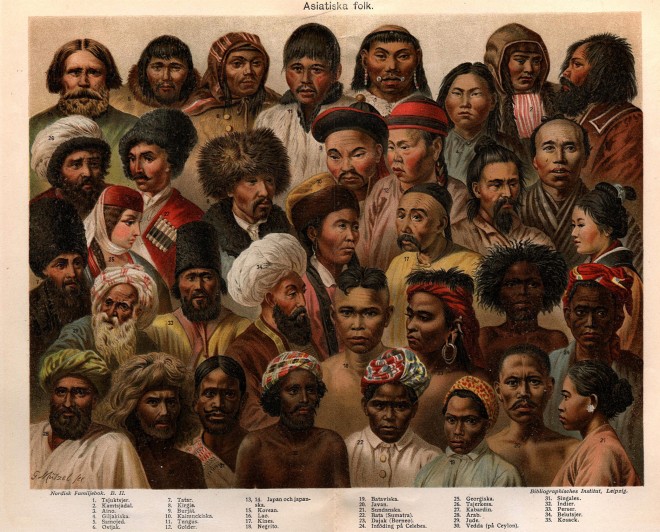

Before Asians were called yellow, they were called white

East Asians were only widely referred to as ‘yellow’ in the late 1700s, says Michael Keevak. Before then – they were white.

How did East Asians come to be referred to as yellow-skinned? It was the result of a series of racial mappings of the world and had nothing to do with the actual color of people’s skin.

In fact, when complexion was mentioned by an early Western traveler or missionary or ambassador (and it very often wasn’t, because skin color as a racial marker was not fully in place until the 19th century), East Asians were almost always called white, particularly during the period of first modern contact in the 16th century.

And on a number of occasions, even more revealingly, the people were termed “as white as we are.”

But by the 17th century, the Chinese and Japanese were “darkening” in published texts, gradually losing their erstwhile whiteness when it became clear they would remain unwilling to participate in European systems of trade, religion, and international relations.

Calling them white, in other words, was not based on simple perception either and had less to do with pigmentation than their presumed levels of civilization, culture, literacy, and obedience (particularly if they should become Christianized).

The term “yellow” occasionally began to appear towards the end of the 18th century and then really took hold of the Western imagination in the 19th.

In 1735 Swedish botanist and physician Carl Linnaeus decided that varieties of homo sapiens could be similarly separated into four continental types, one of which was called homo asiaticus. The color of that group, he said, was fuscus, which can be best translated as “dark.” In 1758, fuscus was silently changed to luridus, meaning “lurid,” “sallow” or “pale yellow.”

In 1795, the German anatomist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach offered a five-race scheme that featured what might be called our first unequivocal labeling of Asian yellowness, couched in a bizarre series of comparisons that stressed the relative decay or lifelessness of the so-called intermediate races.

This human variety, he wrote, was “yellow [gilvus] or the color of boxwood, halfway between grains of wheat and cooked quinces, or the color of sucked out and dried lemon peel: familiar to the Mongolian peoples.”

The most significant aspect of Blumenbach’s conception was that for the first time all the peoples of the East had been lumped together into an explicitly racial category, here called the Mongolian.

“Yellow” was thus a racial marker that had meaning only in relation to the other colors, all of which were defined as against white “normality.” The yellow race became invested with associations that insured that its physical and cultural features were different (or, rather, deviant) from the white European norm.

And for other thinkers far more racially virulent than Blumenbach, the races became part of an explicit hierarchy with European white at the top and African black at the bottom, with the “intermediate” races somewhere in the middle.

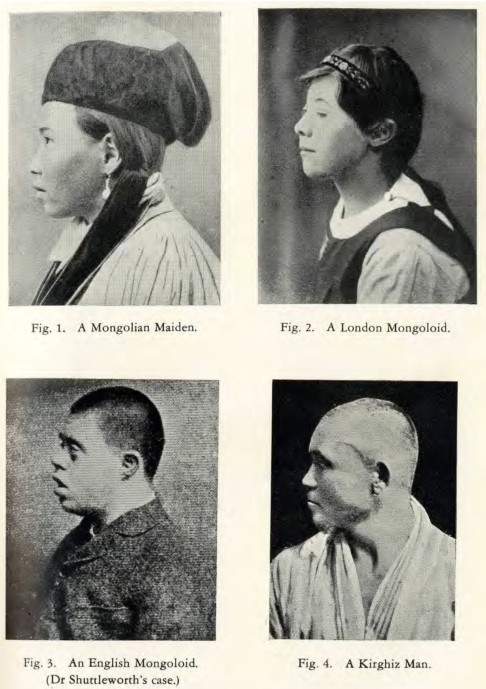

Nineteenth-century medical discourse did much to define the contours of the yellow race, although the emphasis here was on “Mongolianness” rather than color.

Medical research frequently attempted to define the race as embodying certain physical conditions that distinguished them from Caucasians, including the “Mongolian eyefold” (a fold of skin covering the inner corner of the eye), “Mongolian spots” (congenital bluish marks appearing in infants on their lower back or buttocks), and “Mongolism,” today known as Down syndrome.

Each of these conditions was at first supposed to be endemic to the Mongolian race only, and purported to show how the yellow race differed from the healthy and fully developed normality of white European bodies.

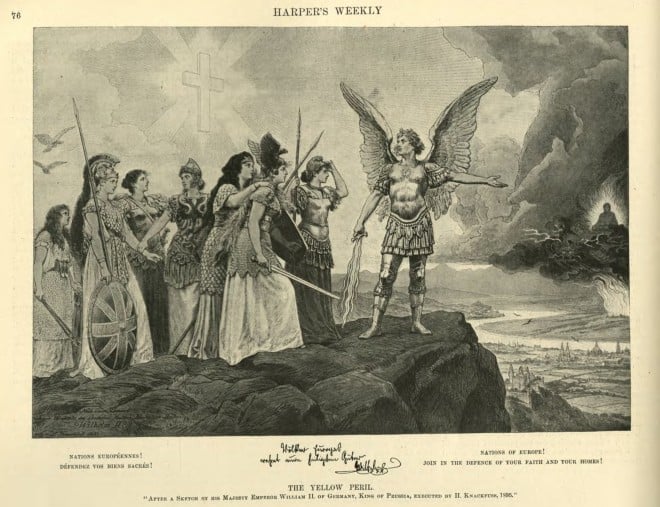

It was at the end of the 19th century that the notion of yellow became canonized in European languages (and East Asian ones). This was the invention of the so-called Yellow Peril in 1895, brought into worldwide circulation by an illustration made after a drawing by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and designed as a call to arms for European nations to protect themselves from the potential onslaught of East Asian military aggression, social degradation, and emigration to the West.

The most immediate danger at this time, it was perceived, came from Japan, which had recently defeated both Russia and China in armed conflict and had begun to build an empire of its own.

It was also at this time that ideas about a yellow race began to be imported into East Asian cultures themselves, along with many other facets of modern Western science and technology.

As might be expected there were a wide variety of responses, rejections, and incorporations, not only to the idea that there were yellow people but also to the contention that all East Asians could be lumped together into a single racial category.

In China, for example, the idea of the yellow race was often seen as an appealing notion since yellow was such a significant color in Chinese culture (such as the Yellow River, the birthplace of Chinese civilization, and the Yellow Emperor, said to be the ancestor of all Chinese).

In Japan, however, yellow carried no such positive associations and the color category was frequently rejected.

“The Chinese were yellow,” it was sometimes said, “not we Japanese, who are far superior to the Chinese and on a par with the Western imperial powers.”

Yellow was a fantasy like all other racial groupings. It cannot be traced back before the end of the 18th century, and it had no basis in anything other than an attempt to distance certain peoples of the world from an equally fantasized concept of whiteness.

Is it not time that we stopped using this term? Why are we still calling people yellow?

Michael Keevak is Professor of Foreign Languages at National Taiwan University and author of ‘Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking’. This essay was excerpted from a paper titled ‘Reconsidering Race.’

China’s sci-fi megahit fights supernovas, online pirates

Inkstone index: China’s online piracy

Before Asians were called yellow, they were called white

What China’s tech names mean (and how to say them)

Snow blankets eastern China

Hope on the road

Stay or go? Chinese students in the US are running out of options

If Chinese scientists, engineers and most importantly politicians have their way, the future will run on pinyin.

Despite the global ambition of China and its tech giants, some of their most strategically important products and projects are still named in Chinese and spelled in pinyin – leading to pronunciation difficulties, let alone any explanation of the meaning behind them.

So here’s a quick guide to decoding the meanings behind the names of some key Chinese tech companies, products and projects.

Huawei Technologies

How to say it: Hwah-way

What it means: Telecoms giant Huawei has grabbed headlines across the world recently after being caught in the middle of an ongoing trade war between China and the US, with the company and its CFO charged with fraud and technology theft, among others.

But it’s not stopped a whole bunch of people from saying the name wrong. Huawei is (more or less) pronounced hwah-way. Hua means China or Chinese, while wei translates to achievement or action.

So the name means “Chinese Achievement” in English – which the company can certainly boast of, as it’s the world’s largest maker of telecommunications equipment. It’s all that achievement, especially in 5G communications tech, that has the US worried.

ZTE Corp

What is means: ZTE Corp, Huawei’s biggest rival in China – and another victim of US-China tensions – has gone with initials to present a friendlier English name. It’s actually short for Zhongxing Telecommunication Equipment: Zhongxing can be roughly translated as “Chinese prosperity” or “China’s resurgence.”

Pingtou Ge

How to say it: Ping-toe ger

What it means: Many of China’s internet giants have accelerated their efforts to gain self-sufficiency in semiconductors. Among them, Alibaba Group Holding, which also owns Inkstone, has given its semiconductor unit a particularly aggressive name – Pingtou Ge Semiconductor.

Pingtou Ge, which translates as “flat head brother,” is the nickname given by Chinese internet users to the honey badger – a small, fearless animal known for its ability to hunt and kill venomous snakes.

Alibaba founder Jack Ma, said he was interested in the animal thanks to its fearless fighting abilities. “There’s no need to know who is the competition or how big the opposing force is, just name a time and a place,” Ma was quoted as saying in a conference in Tianjin in September.

Fuxing bullet train

How to say it: Foo-shing

What it means: Named for a favorite slogan of Chinese President Xi Jinping, Fuxing – rejuvenation – is the nation’s fastest bullet train, with a maximum speed of 220mph and – more importantly for China – a range of technologies that are completely home-grown.

In 2017, the same year the Fuxing bullet train debuted, Xi promised to achieve the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” and restore China to great power status by 2049 – the centennial of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

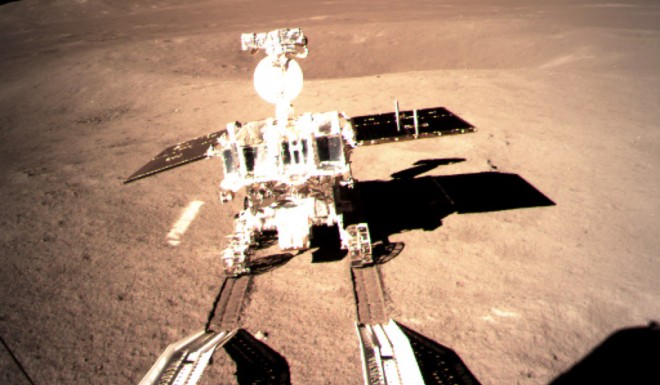

Chang’e, Yutu and Tiangong

How to say it: Chang-uh, You-too, Tee-yen gung

What it means: China’s explorations of space are often associated with Chinese mythology. Chang’e 4, the lunar spacecraft which recently made a historic touchdown on the far side of the moon, is named after the Chinese goddess of the Moon. China’s robotic lunar rover is named Yutu, “jade rabbit.” The rover's name was selected in an online poll and is a reference to the goddess’ pet rabbit.

The name of China's space stations, Tiangong, was also inspired by Chinese mythology. Tiangong refers to the heavenly palace where China’s highest deity, the Jade Emperor, lives.

China’s sci-fi megahit fights supernovas, online pirates

Inkstone index: China’s online piracy

Before Asians were called yellow, they were called white

What China’s tech names mean (and how to say them)

Snow blankets eastern China

Hope on the road

Stay or go? Chinese students in the US are running out of options

Temperatures have dropped across China’s Jiangsu province and snow has blanketed the region to beautiful effect.

Photographers from state-run media organization Xinhua traveled across the province to capture winter in the region.

China’s sci-fi megahit fights supernovas, online pirates

Inkstone index: China’s online piracy

Before Asians were called yellow, they were called white

What China’s tech names mean (and how to say them)

Snow blankets eastern China

Hope on the road

Stay or go? Chinese students in the US are running out of options

Chinese drivers are infamous on the internet for their rudeness and aggression, but this interaction proves there might be some kindness left on the roads.

A polite little girl bowed to the driver of a car that stopped to let her cross a road in southern China’s Guangdong province.

Check out our video, above, for more.