In Hong Kong, 24-year-old entrepreneur “Jay” was brainstorming ideas to make some cash.

On the other side of the world in Britain, his friend and former schoolmate “Nick” was struggling to get his university homework done.

In a moment, a deal was struck. Nick paid Jay HK$500 ($64) to do his statistics homework. Jay earned Nick top marks.

It wasn’t just math. Soon, Jay was writing essays for other students in Britain. Nick helped to find clients for Jay, and as the orders for assignments grew, Jay began to loop in a few other friends as writers for their expanding business.

In less than three years, Nick and Jay have developed a thriving sideline. They have completed more than 90 essays for around 40 students from over six universities in Britain.

But their operation is just the tip of the iceberg of a flourishing industry of homework guns for hire, a practice known in China as dai xie – “ghostwriting.”

More Chinese students have turned to overseas universities in recent years, with their numbers hitting a record 600,000 in 2017.

Studying overseas retains a significant cachet for many in China, and it can also represent an easier path than competing in the grueling nationwide university entrance exam to get into China’s top colleges.

But education experts say that many of the Chinese students who go overseas do not necessarily have the language proficiency to meet the challenges of college education in a foreign language, and so some of them turn to a market of ghostwriters.

There’s no concrete data on the number of Chinese students who use these services, which are not illegal in the UK.

But the rise of ghostwriting business inside and outside the country has put academic honesty at stake, casting doubts on the credibility of degrees attained by Chinese students from foreign universities.

According to private research center Whole Ren Education, 35% of expulsions of Chinese students overseas between 2013 and 2018 were due to academic dishonesty.

Across the globe, contract cheating is on the rise, with as many as one in seven graduates having paid someone else to do a university assignment for them, according to Professor Philip Newton, director of learning and teaching at Swansea University in Wales.

Newton said that as many as 31 million learners worldwide might have employed contract essay writers.

Twenty-two-year-old Hongkonger “Chloe” got into the trade last year to earn money for a holiday in Tibet.

The graduate of a top Hong Kong university charges HK$1 (13 cents) per word and says she easily earns about US$1,000 a month during peak essay seasons.

Her other freelance work in translation, copywriting and tutoring brings in about the same amount but the student essay jobs have several advantages.

“Ghostwriting is much more flexible and it gives you a larger one-time profit,” she said.

“You also learn more from it than tutoring primary school kids, where you keep giving and learn nothing in return.”

Chloe’s word rate is lower than that charged by Nick and Jay, whose clients pay HK$1.20 (15 cents) per word on average, depending on the subject and urgency.

Nick and Jay take a 40% cut for commission, proofreading and administration.

Writers who consistently get good marks can earn well.

Jay said one of the best writers in his stable was paid $2,500 to write an 8,000-word dissertation – about a third more than the $1,840 average monthly salary earned by a fresh graduate in Hong Kong.

“Emma,” a Chinese graduate from a university in Britain’s East Midlands, said that the practice was widespread among Chinese students at her university.

“It was the atmosphere that made you want to hire a ghostwriter. When everyone around you did it, why wouldn’t you do it too?”

And it isn’t hard to find people to do it, either. She said her university email account was often flooded with ads for such services, some of them written in Chinese to reach the 95,000 or so Chinese students studying in the country.

One of the ads was from a company called KJ Essay in which it claimed to have completed 62,570 orders in the nine years it had been running. On December 12, a popular online sales day in China, the company offered discounts, including £20 (US$26) off any essay – although no minimum grade was guaranteed.

In China, the government has been fighting to crack down on ghostwriting, an industry which has been estimated to be worth almost $1.5 billion. In July last year, the Education Ministry announced that students who submitted academic essays written by ghostwriters would be expelled.

As yet, there’s been no word on how successful the measure has been.

Chris Havergal, the news editor of the Times Higher Education magazine, urged Western universities to be more proactive in combating contract cheating to protect their own standards.

“The integrity of the qualifications offered by leading Western universities is central to their appeal to international students, so combating contract cheating should be a priority for institutions and policymakers,” he said.

Imagine: the rogue scientist who stops at nothing to push the bounds of technology – and ethics. His frenzied research leads to the birth of twins– but inadvertently gives them mental abilities far beyond those of the average human.

This is no superhero movie. Instead these may have been the actions of controversial Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who shocked the world when he claimed last November to have created the world’s first gene-edited babies.

Now it turns out he may have unintentionally enhanced the brains of the children whose genes he altered.

He, who was found to have “seriously violated” Chinese laws in the pursuit of his work, likely changed the cognitive functions of twin girls when he used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to render them resistant to HIV, the MIT Technology Review reported.

He used the tool to disable the CCR5 gene that allows HIV to infect human cells.

But neurobiologist Alcino J. Silva, from the University of California, Los Angeles, who co-authored a 2016 study that found CCR5 was linked to deficits in learning and memory, said the gene editing had likely affected the babies’ brains – though the exact effect was impossible to predict.

“The simplest interpretation is that those mutations will probably have an impact on cognitive function in the twins,” Silva was quoted as saying.

The experiment sparked a global backlash after He publicized the births of the gene-edited twins, nicknamed “Lulu” and “Nana.”

Last November, He said at an international human genome-editing summit in Hong Kong that he had read the research conducted by Silva and others, which found the removal of the CCR5 gene in mice significantly improved their memory.

“I saw the paper, and I believe it needs more independent verification,” he said in response to a question about whether he had inadvertently improved the brains of the gene-edited babies. “I [am] against using genome editing for the enhancement.”

New research on the CCR5 gene published last Thursday in the journal Cell, co-authored by Silva, found links to the gene and school performance, suggesting links to human intelligence.

“Could it be conceivable that at one point in the future we could increase the average IQ of the population?” Silva told the MIT Technology Review. “I would not be a scientist if I said no. The work in mice demonstrates the answer may be yes. But mice are not people. We simply don’t know what the consequences will be in mucking around. We are not ready for it yet.”

Chinese authorities have said He and his team will be punished for performing human embryo gene editing for the purpose of reproduction, which is banned in the country, as well as forging medical reports to allow his work to go ahead.

Trump puts new tariffs on hold after talks with China

Pixar’s first Asian director wins an Oscar for a film about a dumpling

Inkstone index: China’s Oscars record

Did the gene-editing Chinese Dr. Frankenstein create superhumans?

The best photos of Hong Kong, according to National Geographic

How to lead your son home

The Chinese students who hire ghostwriters to get them through college

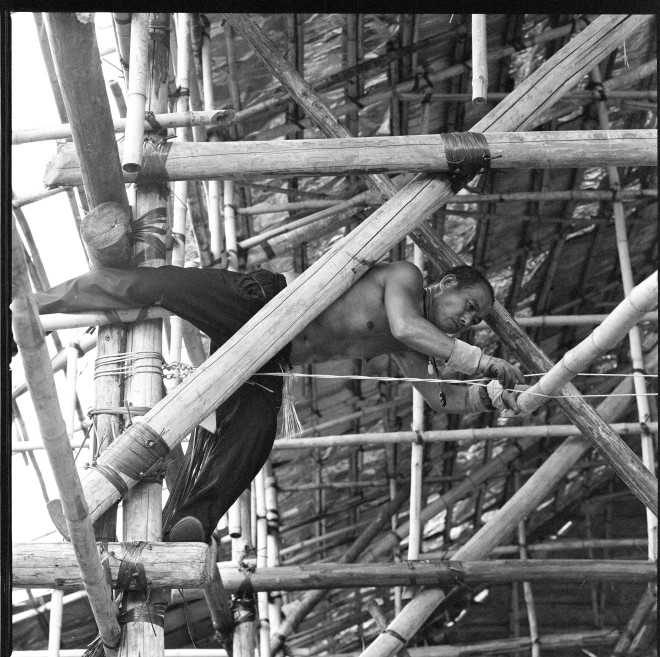

The winners of the 2018 National Geographic Wheelock Hong Kong Photo Contest have been announced.

Here’s a selection of some of the best shots taken from across the city.

The theme of this year's contest was “Hong Kong Story: Nature, city and people.”

The contest sought to capture the ways in which urban life and nature intertwine in Hong Kong.

Photographers spanned the city to capture the raw energy of this clash of people and nature, from markets to public parks.

Some parts of Hong Kong have become a photographic tourist trap, but many of those famous locations have not made this year’s list.

The winning photos mostly focused on seeing Hong Kong through a unique lens or viewpoint.

Trump puts new tariffs on hold after talks with China

Pixar’s first Asian director wins an Oscar for a film about a dumpling

Inkstone index: China’s Oscars record

Did the gene-editing Chinese Dr. Frankenstein create superhumans?

The best photos of Hong Kong, according to National Geographic

How to lead your son home

The Chinese students who hire ghostwriters to get them through college

A clever father in eastern China’s Shandong province was faced with a problem when his young son refused to follow him home.

His solution: to use a fresh strawberry to lure his son into following him through the market.