Hong Kong Central Police Station restoration: how city’s most ambitious heritage project overcame the odds

The new Tai Kwun complex partially reopened in May, with 16 buildings restored, adapted and merged with contemporary materials that saw local restorers learn new techniques – but also regular clashes with government officials

More than half a million clay tiles made in China’s Guangdong province. Forty thousand red bricks imported from northern England. About 200 prison cells preserved. And the most striking figure of all: HK$3.8 billion (US$485 million) spent so far transforming Hong Kong’s historic Central Police Station complex into a 300,000 square foot (27,870 square metre) public heritage and cultural centre.

Tai Kwun – colloquial Cantonese for “Big Station”, and now its official name – partially reopened at the end of May, offering a rare chance in Hong Kong to explore a host of magnificent heritage buildings.

Register and follow to be notified the next time content from Art is published.

Hong Kong artist Wong Tong is trying to keep silk-screen printing alive

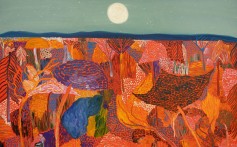

- ‘I draw on my senses,’ says Wong Tong, whose paintings, sculptures and installations are inspired by music

- He also runs silk-screen printing workshops ‘to preserve these traditions, especially in our digitised age’

When Wong Tong was young, he spent hours in the classroom doodling while songs played on a loop in his head. “I daydreamed a lot at school,” says the 36-year-old Hong Kong artist. And with lyrics such as “You may say I’m a dreamer”, it is no wonder John Lennon’s 1971 tune Imagine was a persistent earworm.

Today music continues to inspire Tong’s paintings (mainly in oils), sculptures and installations, in particular the sounds of Shigeru Umebayashi, the Japanese composer who worked on scores for films such as Wong Kar-wai’s 2046 and Zhang Yimou’s House of Flying Daggers (both 2004).

“I draw on my senses,” Tong says. “Songs arouse memories, and I paint the characters that I see and hear from my favourite films … I paint sound.”

Tong is heavily influenced by traditional crafts and cultures, and silk-screen printing is part of his creative repertoire; the technique’s layering process is similar, he says, to the layered notes and patterns of a song. Take, for instance, his silk-screen print Hwit. In this piece, Tong hears the music of Japanese electronic pioneer Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Tong shares his silk-screen printing techniques in workshops at Sin Sin Fine Art, in Aberdeen, where he has been a resident artist since 2011. In his next workshop, scheduled for February 6, participants will create a fai chun, a traditional decoration hung in doorways at Lunar New Year.

Silk-screen printing can be traced to China and Japan as far back as the 10th century. But Tong is not concerned with which country was the first to use the technique. His goal is to ensure the ancient craft is not lost.

“I want people to create art with their hands, to get a sense of touch instead of just capturing something with a camera on their phone,” he says. “It’s important to preserve these traditions, especially in our digitised age.”

On a wall at Sin Sin Fine Art is more evidence of Tong’s love for ancient cultures: an installation comprising bamboo rain sticks – long and hollow traditional African instruments, partially filled with pebbles, that mimic the sound of rain when tipped from side to side.

“Children in Africa use these rain sticks to pray to the gods for rain,” Tong says. “Bamboo is a common material in Hong Kong – you see it used as scaffolding at construction sites – so I wanted to bring this kind of spiritual ritual to Hong Kong, to combine the two ancient cultures.”

Tong’s 2018 exhibition “Hidden Gaze” featured handmade instruments, such as metal tongue drums and ukuleles, that blend traditional and modern elements, and guitars made from upcycled materials. “I want to give objects a second life,” he says.

SCMP Editorials

Opinion

Harry's View

Letters