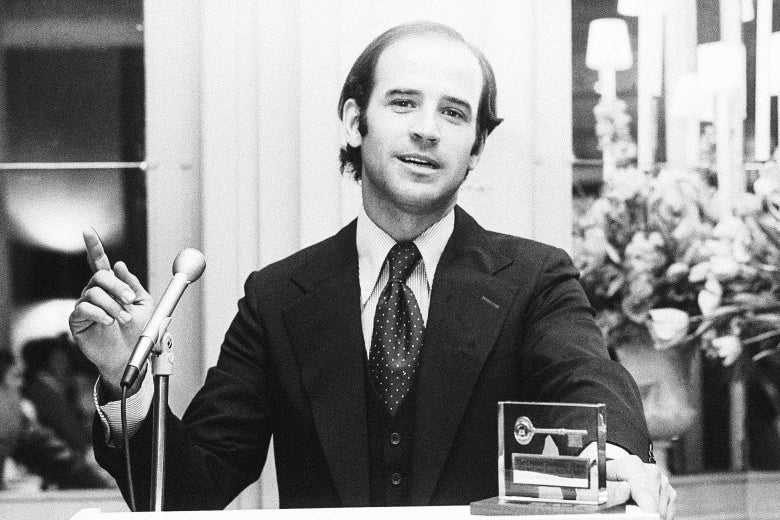

A little more than a week before Election Day 1972, readers of Wilmington, Delaware’s major newspapers were greeted with a series of advertisements from 29-year-old New Castle County Councilman Joseph R. Biden Jr. Biden was running for U.S. Senate against an older, much more established candidate, the two-term Republican incumbent Sen. Cale Boggs. The ads were meant to highlight how Boggs, and his generation, were out of touch.

“Cale Boggs’ generation dreamed of conquering polio,” read one ad. “Joe Biden’s generation dreams of conquering heroin.”

“To Cale Boggs, an unfair tax was the 1948 poll tax,” went another. “To Joe Biden, an unfair tax is the 1972 income tax.”

“Joe Biden,” the bottom of each spot read. “He understands what’s happening today.”

Norm Lockman, a Wilmington News Journal reporter at the time, wrote of the new messaging, which Biden had developed himself and which varied depending on what part of the state he was trying to reach. To those near the beaches in downstate Delaware, Biden would say that “thirty years ago, caring for the environment meant picking up bottles and beer cans on Rehoboth Beach … and now it means saving the beach.” In the north, around Wilmington, the pitch would be, “in 1950, Cale Boggs promised to keep highways growing; in 1970 Joe Biden promises to keep trees growing.” Lockman called this the “dear old dad” approach: “Dear old dad may have been right for his time—and I love him—but things are different now.”

A little more than a week later, Biden pulled off one of the great political upsets of his time, defeating “dear old dad” Cale Boggs by a little more than 3,000 votes. He wouldn’t even meet the minimum 30 years of age for serving in the Senate until a couple of weeks after the election.

“It really was a shock,” Bob Frump, then a reporter for the News Journal who covered the campaign, told me recently. “I thought Joe had a chance at it, based on my ward interviews. But when we were looking at results in the newsroom, no one really believed that it was coming in that way.

“I think what people really wanted,” he said, “was a new future.”

Biden’s huge 1972 upset gave way to a 36-year Senate career, eight years in the vice presidency, and now a third run for the presidency. Biden then found a way to captivate young people—and many of their parents—looking for something new, charismatic, authentic, and inspiring. Biden now, like Boggs then, is a popular, charming mainstay whom many voters have viewed fondly for decades, but whose political longevity makes him susceptible to calls for new blood. To state the obvious, a lot has changed since 1972. But going back to that race—to a time just before the tragedy that would come to define Joe Biden, when he was still all hope and promise—reveals just how little has changed about the middle-ground politics of the Democratic front-runner.

The often joked-about traits of “Uncle Joe” Biden did not develop over time. They existed from the start.

Shortly after his election to the New Castle County Council in 1970, the News Journal wrote, “one of [Biden’s] colleagues quipped that he was the only man he knew who could give an extemporaneous 15-minute speech on the underside of a blade of grass.”

The loose talk that would give him numerous headaches over the years was already apparent in a late 1970 News Journal profile, one of the first features to detect and suss out his ambitions for the 1972 election and beyond. Biden told reporter Jane Harriman, for example, that he wanted his wife, Neilia, to stay home for the time being to “mold my children.” While he cautioned that he wasn’t “a ‘keep ’em barefoot and pregnant’ man,” he was “all for keeping them pregnant until I have a little girl.” Neilia would deliver the couple’s first daughter, Naomi, in late 1971.

Verbal discipline was never Biden’s strong suit. Just as with his 2018 presidential campaign, Biden had trouble keeping his plans under wraps ahead of the official Senate announcement. At a downstate event in November 1971, Biden referred to himself as a “candidate,” only to correct himself later in the day that he was only “90% sure” he would run for Senate. (He wanted “to check for support in two more places” before making his decision.) The Morning News titled its brief write-up of the slip, “Biden to [oops] MAY try Senate.”

Early the following year, Biden handicapped his own chances of beating Boggs. “If I were a bookie, I’d give five-to-one odds right now that Boggs will be reelected,” he told the Morning News. Those were about the best odds Biden was going to get. No one thought that Biden—or any Democrat in Delaware—would beat an institution like Cale Boggs, an undefeated politician who was assumed to continue his streak in 1972, if he chose to run again.

Boggs, a moderate Republican, was considered “the lovable old man of Delaware politics,” Curtis Wilkie, a News Journal political reporter at the time, told me recently, or as Norm Lockman wrote in 1972, Boggs’ “sweet grandpa image” had “made him one of the best liked men in Delaware.” He was a pro-business Republican whom labor had supported in the past. In his 2007 memoir, Biden wrote about all of the people he would run into in Wilmington who told him it would be lunacy to challenge Boggs, who had earned the trust of so many Delawareans over his decades of service. One “older attorney,” Biden wrote, told Biden of a dispute between players at a poker game he had recently hosted. No one at the table could resolve it.

“You know what we did, Joe?” the attorney told Biden. “We called Cale Boggs to settle it.”

Part of the reason Biden was able to glide to the Senate nomination that summer was that all of the “realistic” Democratic prospects—a former governor, a state Supreme Court chief justice—had flatly rebuffed overtures to run. The state Democratic Party was more concerned with taking back the governor’s mansion that year, and Biden was viewed as little more than a sacrificial lamb in the Senate race. Biden was more confident in his own abilities but also felt he had little to lose: His county council seat had been redistricted in Republicans’ favor, giving him a limited future there.

One thing Biden had going for him was Boggs’ own reluctance to run for reelection. Boggs had decided not to seek reelection as early as 1968, his former aide, William Hildenbrand, said in a U.S. Senate oral history. But the Republican powers-that-be staged an intervention, telling Boggs that they needed him on the ticket to goose turnout for the governor’s race. Nixon, at one point, came to Delaware to plead with Boggs to run for the good of the party. The president was, among other things, concerned about a potentially divisive primary between Wilmington Mayor Hal Haskell and Rep. Pete du Pont for the Republican Senate nomination should Boggs not run. There was even talk that Boggs could step down right after his victory and allow a Republican governor to appoint Haskell or du Pont as his replacement. Boggs, a party man, reluctantly agreed to run one more time, but didn’t think he’d have to work much for it. Biden, meanwhile, was holding about 10 meet-and-greet coffees with voters a day in an effort to get his name out.

Biden had one more advantage: 1972 was the first year that 18-year-olds were able to vote. And Biden wasn’t just a young candidate for federal office. He was the candidate of the young, too.

“The comments of the young volunteers” on Biden’s 1970 county council campaign, Jane Harriman wrote in her profile that year, “are often one squeak above the equal of a Beatlemaniac.” In that first race, an “army of 150 or more high school, college students, and young professionals worked around the clock for him from June until Nov. 4.”

Replicating this youth volunteer network would be key to Biden’s first Senate run.

When he started campaigning in 1972, Biden spoke of running a “minimally financed” campaign, spending somewhere around $100,000 or $150,000. That meant very little television advertising and very little paid distribution of literature. Instead, the Biden campaign—which was largely a family affair run with his friends and siblings, plus help from a media consultant in Boston—chose to distribute its literature another way: by having young volunteers hand-deliver it throughout the state.

“A single statewide mailing cost $36,000, which we couldn’t afford,” Biden wrote in his memoir. “So [Biden’s sister and campaign manager] Val invented the Biden post office. Once a week, either Saturday or Sunday, her army of volunteers hand-delivered our private campaign newspaper to about 85 percent of the households in the state. By the middle of October, people would be waiting on Saturday mornings for a kid to come to the door.”

And many of them really were “kids.” In an early 1972 piece, Bob Frump noted in a News Journal story that “High School Students for Biden” committees had already been forming even before Biden’s official announcement. Biden told Frump that while he would be reaching out to college students, “the main emphasis will be on the younger students, the younger laborers.”

Biden would frequently speak to high school classrooms during the campaign, and not just because he was trying to get the 18-year-old seniors to vote for him. He was also trying to get the students, of all ages, to change their parents’ minds.

Valerie Biden later said this strategy determined the outcome of the race. “I attributed [the outcome],” she told journalist Jules Witcover for his 2010 biography of Biden, “to the parents who said to us, ‘Anybody who could get my child out of bed at six o’clock on Saturday morning’ ” to distribute campaign literature “before their football game at ten o’clock in school; to do this, I’ve got to take another look at this person, because there must be something good about him.”

By targeting unshaped young minds rather than the student activists of the time, Biden was able to harness the youth energy without adopting a liberal line across the board. In fact, he worked hard to create some distance between himself and the left, as one of his greatest risks was being perceived as one-and-the-same as George McGovern, the liberal Democratic presidential nominee that cycle.

“There wasn’t much of an alternative to Nixon for a middle-of-the-road voter” in the 1972 presidential race, Bob Frump told me. Biden had to create his own distinct alternative to Republicans that cycle, with headwinds coming from the top of the ticket.

Biden “shuns the label of ‘liberal,’ ” the News Journal wrote in a June 1972 story that quoted Biden as saying, “I’m not as liberal as most people think.” He made a point of emphasizing that his student volunteer army was proprietary to his campaign, not leeched off of McGovern’s organization. And he avoided scorching culture war debates, always trying to redirect conversations back to local or pocketbook issues like crime, the environment, corporate loopholes in the income tax, or protecting Social Security.

“It’s not that Joe distanced himself for McGovern [personally], but he certainly did on the issues,” Frump told me. “I remember him being asked, on a typically liberal issue then, about legalization of marijuana in 1972. And he said, I’m not biting on that question, I’m not going to answer that, because it detracts from what I really want to do.”

On so many issues, Biden would offer a position that could appease liberals without offending more middle-of-the-road voters. For instance, while he didn’t support marijuana legalization, he did, in one campaign ad, say that “the possession of marijuana is a misdemeanor—a minor offense. The police should treat it that way, and devote the greater part of their efforts to heroin.” He was against the Vietnam War and often criticized Boggs for not standing up to Nixon to end it. But he also refused to support amnesty for draft dodgers, and even in his opposition to the war, he couched it in pragmatic terms.

“I didn’t argue that the war in Vietnam was immoral,” Biden wrote in his memoir. “It was merely stupid and a horrendous waste of time, money and lives based on a flawed premise.” (The line is awfully similar to one Biden’s eventual boss, Barack Obama, used to describe his own opposition to the Iraq war: “I don’t oppose all wars … What I am opposed to is a dumb war.”)

On race-related issues, Biden also picked his battles carefully.

As a councilman, he had pushed for more public housing. When, as he told Harriman in 1970, someone called him saying, “You nigger lover, you want them living next to you?” he responded, “If you’re the alternative, I guess the answer is yes.”

But he also made clear in that same profile that he wasn’t entirely with the vanguard left on racial issues. “I have some friends on the far left, and they can justify to me the murder of a white deaf mute for a nickel by five colored guys,” Biden told Harriman. “But they can’t justify some Alabama farmers tar and feathering an old colored woman.” During the campaign, he also staked out a firm position against busing to reduce segregation, telling a group of Young Democrats in March 1972 that it was a “phony issue which allows the white liberals to sit in suburbia, confident that they are not going to have to live next to a black.”

Biden’s positioning on some issues earned some eye-rolls. In a July 1972 column in the Morning News, Eleanor Shaw wrote that “Democrats who know insist that Biden is more Conservative than Delaware’s senior senator. That means that in November you can either vote for the oldest young Democrat or the youngest old Republican.

“Ah, yes, another thrilling six years ahead,” she concluded.

But Biden, as his law school friend Roger Harrison told me, possessed the “unique art of being able to disagree—say no—and have people come away respecting his difference.” At that same March 1972 meeting of Young Democrats, Biden spoke of the need for politicians to be more blunt, especially to those with whom they disagree.

“It’s about time politicians stop making pro-black speeches before black groups and pro-labor speeches before the labor groups,” he said. “People don’t want to hear what they think you think they want to hear.”

The issues, then, were almost secondary to Biden’s good fortune. “When he is with the young people devotedly supporting him, the light in the girls’ eyes has little to do with abstract political insight,” Norm Lockman wrote dismissively of the Bidenmaniacs in October 1972, a couple of weeks before the election. “The girls think he’s sexy and say so with little provocation.” The young men, meanwhile, “get that ‘new hero’ look when Biden raps about how the old guard has bungled things.”

Grossly stereotypical gender portrayals aside, it was true that Biden, regardless of his middle-ground positions on certain issues energizing the New Left in the early ’70s, found a way to captivate young people looking for an alternative to Boggs that Delaware hadn’t previously known it wanted. And Biden was able to marry the support of his young volunteers with traditional Democratic constituencies, like labor and the Wilmington machine. The Boggs campaign didn’t acknowledge the ferocity of the challenge on its hands until the fall, when it was too late.

“Joe ran as this bright young family man, his wife was very attractive, they had the three small children,” Curtis Wilkie told me. “He had a lot of things going for him in terms of image, if not experience. He was a good speaker, smart, charming, funny, self-deprecating, and was free of any kind of scandal. He was just kind of a fresh face.”

Or, as Jane Harriman wrote presciently two years earlier in her profile, “He had the look—both triumphant and sad—of a young man who believes the world is his, and knows he is yet to be tested.”

Pulling off the political upset of a lifetime to win a U.S. Senate seat at age 29 was not the most consequential moment of 1972 for Joe Biden. The story of that improbable victory has mostly been forgotten because of the tragedy that occurred immediately after it—when his wife, Neilia, and daughter, Naomi, were killed in a car crash that December while Joe was preparing for his new job in Washington.

When Biden spoke about his wife and daughter at the memorial service, he talked about how the night before, he and Neilia had worried that things were “too good,” and something terrible was waiting around the corner.

“We had known something was going to happen,” Biden said. “We had decided not to have a fourth child because of a fear that something would happen to it. … We had three beautiful children. Now I have two.”

An aura of tragedy has loomed around Biden ever since, one that resurfaced acutely in 2015 when his son, Beau, died of cancer. And for someone who served 36 years in the Senate and eight as vice president, there’s still a sense of melancholic, unmet potential about him. That same running mouth that Biden’s fellow county council members diagnosed in the early 1970s has gotten Biden into so much trouble over the years, preventing him from advancing to the job many Democrats assumed he’d eventually attain.

“He’s Irish, for god’s sake. He’s full of blarney, if you will, he always has been. He’s a bullshit artist,” Wilkie, who was with Biden in Washington the day of Neilia’s crash and has kept up with him over the years, told me. Wilkie said this almost admiringly, the way you might about a well-meaning friend who can’t help himself. Wilkie told me a story about his son, then in college, who in 1987 told his father that he was thinking about working for Biden’s presidential campaign that cycle.

“I said, well, go ahead and do it, you can do it with my blessings,” Wilkie recalled. But, he added, “Joe’s going to fucking implode before he ever really gets started.”

The inevitable implosion, amid a plagiarism scandal, came about a week too late for Wilkie’s son to get back in school for the fall semester. Biden similarly spent the first day of his bid for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination trying to explain away one of his most canonical gaffes.

In his third try for the presidency, Biden is neither young nor the top candidate of the young. He has even baited the young, saying in 2018 that the “younger generation now tells me how tough things are. Give me a break. No, no, I have no empathy for it.”

He is, however, the front-runner, with dominance among older Democrats as the source of his early polling strength. Instead of pitching generational change, Biden is selling a return to normalcy. It remains to be seen who, if anyone, can rally enough young voters and convince older voters that Biden has served the country well, but it’s time for something new. If such a figure does emerge, the message of Biden ’72 is as good a road map as any: He might have been right for his time, but things are different now.

Support our independent journalism

Readers like you make our work possible. Help us continue to provide the reporting, commentary, and criticism you won’t find anywhere else.

Join Slate Plus