When the coronavirus pandemic spread worldwide in March, it looked like an unprecedented catastrophe for global democracy. We knew the most effective ways to control the spread of the virus were to prevent large crowds from gathering and to track whom infected people had come in contact with. By and large, citizens not only permitted leaders to take these measures, they welcomed them. And it seemed likely that governments would exploit these new laws and surveillance systems in order to consolidate power for themselves in the name of combating the virus. The threat of the virus’s global spread also necessitated unusually strict border controls—a tailor-made pretext for the illiberal, nativist movements that have recently been ascendant in Western democracies to enact their wish list of policies. The virus had first emerged, and was first brought under control, in the world’s most powerful authoritarian state, and it seemed inevitable that China’s draconian methods for addressing it would be exported worldwide.

Almost 11 months since the virus was first identified, and eight since it became a truly global event, the pandemic has in most respects turned out to be as bad, if not worse, than early predictions. But I’m happy to say that those who were predicting widespread democratic collapse—and I was definitely one of them—got this one wrong. Rather than strengthening undemocratic movements and leaders, the pandemic has exposed them. Rather than isolating and intimidating citizens, it has more often stirred them to action. This should be cause for some cautious hope as the U.S. faces its own crucial COVID-era test next week.

The most clear and dramatic demonstration of COVID-era democracy in action can be found in Belarus, where mass protests and strikes are still ongoing more than two and a half months after longtime dictator Aleksandr Lukashenko “won” reelection in a highly dubious vote. After 26 years in power, Lukashenko may simply have overstayed his welcome. But the mass movement against him was largely sparked by his obstinate refusal to take almost any action to contain the coronavirus and mockingly dismissive attitude of the damage it was causing. It’s ironic that Europe’s most repressive state is facing its strongest challenge ever because of its refusal to impose any sort of control.

Or take Bolivia. One year ago, leftist President Evo Morales was removed by the military after a disputed election. A right-wing interim government took his place and, despite having almost no democratic legitimacy, set about rolling back many of his signature programs. But that government also completely failed to control the coronavirus—Bolivia has one of the world’s highest death rates—completely undermining public trust in an already controversial regime. Morales’ party was returned to power in elections earlier this month.

In Thailand, the government of Prayut Chan-o-Cha—the general–turned–prime minister who took power in a coup in 2014—has actually done a remarkably effective job containing the virus. But the economic crisis that accompanied it exposed the country’s stark inequalities and ignited anger against the wealth of the ruling elite. Mass protests are pretty common in Thailand, but the movement that has swept the country in recent months is different in that it’s directly confronting the country’s long sacrosanct monarchy.

None of these examples are unmitigated success stories. Lukashenko and Prayut are still in power. Morales’ movement did not exactly have sterling democratic credentials itself. But the public mobilization in each of these cases has been unprecedented, and these governments will have a hard time going back to business as usual.

There are other ways in which the political effects of COVID-19 have been less dire—or at least more complex—than initially feared. China attempted to turn its success containing COVID into a soft power victory via “mask diplomacy,” but neither governments nor the public in most countries around the world are buying it. China’s initial failure to stop the spread of the disease that has transformed life on the planet and the role that the regime’s secrecy and authoritarianism may have played in that failure have only increased skepticism about China’s political model. At the same time, Taiwan’s COVID response—perhaps the most successful in the world—has only made its democratic and transparent political model look more appealing.

Though conspiratorial anti-lockdown movements in Europe are getting plenty of attention, the coronavirus has actually been politically disastrous for extremist, far-right parties like Alternative for Germany and Austria’s Freedom Party, as voters have gravitated toward steadier, more technocratic leadership.

This year has also seen a global mass movement against racism and police brutality, bringing protesters onto the streets from Minneapolis to Lagos. According to some estimates, as many as 15 million to 26 million people in the U.S. may have participated in the demonstrations, making them the largest political movement in the country’s history. Yes, these protests to make societies more inclusive and democratic were sparked by specific acts of state violence and by grievances going back centuries, but it’s hard to imagine the eruption of public backlash would have been as dramatic or as sustained without the many assorted stresses of COVID and lockdown.

There are at least three big reasons why predictions of COVID causing a democratic recession have proved inaccurate.

The first is epidemiological. When the protests following the killing of George Floyd broke out in cities across the U.S. over the summer, there were initial fears it would lead to an explosion of new virus cases. But it turned out that it’s relatively safe to hold mass gatherings, as long as they are outside and participants wear masks. If it had turned out that the virus spread easily in outdoor gatherings, the political history of the past several months would have turned out very differently.

The second factor is technological. Early in the pandemic, it was often assumed that smartphone contact tracing systems—presumably implemented by governments with the cooperation of big tech companies—would be a key weapon in fighting the outbreak, raising fears about the heightened surveillance powers that would accompany them. As it turned out, these systems have been a bust outside of East Asia, and there has been political pushback in cases where they seemed too invasive. This may be lamentable from a public health perspective, but it does not appear at this point like track and trace will be a Trojan horse for taking Chinese-style digital totalitarianism worldwide.

The third is political. There are some leaders—Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, for instance—who used the state of emergency to undermine democratic institutions. But more often, dictators as well as autocratically inclined elected leaders, including Lukashenko, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, either denied the severity of the crisis, suppressed information about it, or embraced pseudoscientific solutions. (Tanzanian President John Magufuli, who this week appears to be in the process of stealing an election after months of claiming to have defeated the coronavirus through prayer, is another notable example.)

Why would these leaders pass up such an obvious opportunity to seize power through an aggressive coronavirus response? The Bulgarian political scientist Ivan Krastev argues that “Authoritarians only enjoy those crises they have manufactured themselves. They need enemies to defeat, not problems to solve.”

This doesn’t mean that authoritarian governments can’t respond effectively to a crisis like COVID. Look at Vietnam or Rwanda. If there’s any common trait in the countries that have met this challenge well, it’s a high level of trust between the government and its people. That’s not typically present in countries where the government thrives on repressing the opposition, demonizing minorities, or exploiting divisions.

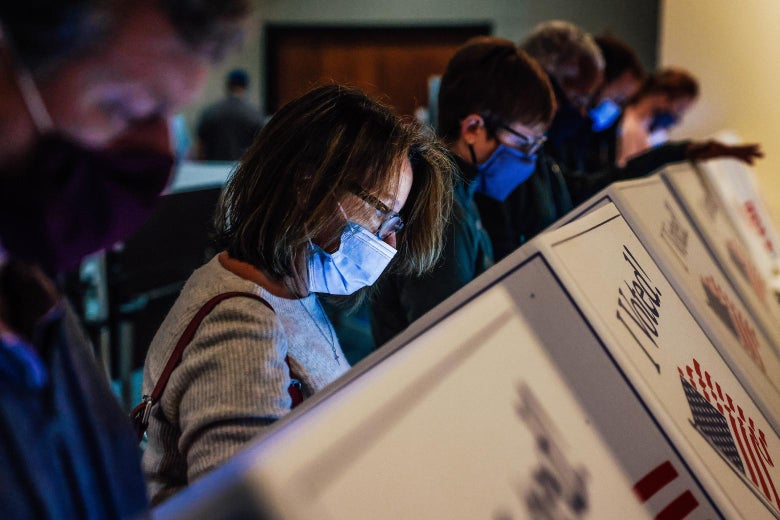

And that brings us to the upcoming U.S. election. If next week’s result is disputed, decided in the courts, or widely seen as illegitimate, many will probably blame the virus for introducing chaos and confusion into the election. After all, COVID led to the rushed adoption of voting by mail in many states, opening the door to all sorts of chicanery in the vote counting. But this would be missing the point. Democracies around the world, from wealthy established ones like South Korea to poor fragile ones like Bolivia, have shown that it’s actually not that difficult to hold a safe and fair election during the pandemic. If the worst-case scenarios come to pass, the blame should be placed on America’s outdated and idiosyncratic electoral system, the partisan capture of the courts, and the occupant of the White House. These would have been factors with or without the virus.

On the other hand, if Joe Biden’s victory is clear and commanding enough that even this administration can’t successfully change it, the pandemic likely will have something to do with that. Nothing has illustrated the dangers of Donald Trump’s corrupt and autocratic governance more than his failed response to the pandemic, and polls suggest that voters—including groups such as older voters, who supported the president in the last election—understand that.

It would be premature to say that we’re in for a democratic flourishing, post-pandemic. Democracy was in decline before COVID hit, and that decline may very well continue. But it’s also clear that the virus has been a generally destabilizing force, weakening political institutions around the world and in many cases contributing to public distrust of those institutions. In many respects, that’s been a bad thing, triggering a resistance to masks and other common-sense measures. But it’s also likely made it harder for powerful institutions to put one over on the public, to justify authoritarian power grabs in the name of public safety. It’s not clear what ultimate effect this destabilization will have on politics around the world, but the range of possible futures is much wider than it was a year ago.

Support our 2020 coverage

Slate is covering the election issues that matter to you. Support our work with a Slate Plus membership. You’ll also get a suite of great benefits.

Join Slate Plus