Millions of people in Southeast Asia rely on the mighty Mekong River for food. China denies that its hydroelectric plants have “turned off the taps” on the lower stretches of the waterway.

Fishermen in northeast Thailand have seen catches in the Mekong River plunge, while some farmers in Vietnam and Cambodia are leaving for jobs in cities as harvests of rice and other crops shrink.

The common thread is erratic water levels along Asia’s third-longest waterway.

Water flows along the 2,700-mile Mekong shift naturally between monsoon and dry seasons, but non-government groups say the 11 hydroelectric dams on China’s portion of the river – five of which started operating in the past three years – have disrupted seasonal rhythms. This threatens food security for the more than 60 million people in the lower Mekong that rely on the river for a livelihood.

“Naturally, Mekong water rises and decreases slowly about three to four months from highest to lowest levels,” said Teerapong Pomun, director of the Mekong Community Institute, a non-governmental organization based in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

“[But now] the water levels fluctuate almost every two to three days all year, and every year, because of the dams.”

Beijing has taken issue with assessments that accused Chinese dams of causing shifts in Mekong water levels, especially an April think tank report that said China was withholding water upstream, citing satellite data. China said the report failed to recognize that low rainfall caused a drought in 2019, the worst to hit the region in 50 years.

Whatever the argument, the food supply and livelihoods for tens of millions of people are at stake. The coronavirus pandemic is adding another twist to the troubling dynamic.

“The situation in the Mekong is worrying as the prolonged drought poses dire threats to regional countries from various aspects, particularly in terms of food security,” said Zhang Hongzhou, a research fellow with Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

The Mekong River nourishes wetlands known as Asia’s rice bowl. Because so many people rely on the river disruptions to its water levels can be devastating.

“Farm crop yields decrease, animals die, which has a huge impact on the livelihood of people,” said Bunleap Leang, the executive director of 3S Rivers Protection Network, a non-governmental organization that works to support dam-affected communities in northeastern Cambodia.

Mekong water levels fell to a record low in July last year, causing Vietnam, the world’s third-largest rice exporter, to declare a state of emergency for the five provinces in the Mekong Delta that produce more than half the country’s crop. Local authorities have warned the drought could run into May or longer.

Farmers are especially hard hit because when the water level falls, they have to buy more fuel for water pumps so their costs increase at the worst time, Pomun said.

This is driving farmers from their rice fields to find other work, while Thai fishermen on the Mekong are pulling in empty nets, he said.

Besides the impact on agriculture, the Mekong and its tributaries make up the largest freshwater fishery in the world, and catches are a mainstay of the diet for local people.

Fish account for as much as 82% of animal protein consumed locally, according to a report by the Mekong River Commission (MRC), an intergovernmental organization representing Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand.

The inland fisheries of the Mekong basin are a “lifeline” for the people of the region, said the MRC on its website, which warns of “severe” consequences from disruption to the catch, especially as the population of the Lower Mekong is estimated to rise to 100 million people by 2025 from the current 60 million.

Those consequences are already arriving, according to a 2018 report by the MRC, which was updated in January last year.

“Fisheries production is expected to decline substantially upstream because of the hydropower dams,” it said.

The report forecast a possible 40% drop in fish catches through 2020 and as much as 80% less by 2040.

The report shows that as populations are forecast to increase along the Mekong, fish stocks are likely to collapse through a combination of the dams, illegal fishing prompted by shortages and climate change.

In Cambodia, fish catches have plunged in the Tonle Sap, Southeast Asia’s largest inland lakes.

The MRC report predicted Tonle Sap annual average fish production would fall from 385,000 to 260,000 tons by 2020, and to 220,000 tons by 2040.

China’s ambitions on the river, which originates in the Tibetan Plateau and is known as the Lancang in Chinese territory, can be traced back to the 1950s, when engineers conducted surveys of the river in southwest China.

From the 1980s, China ramped up hydroelectric dam construction to meet growing power demand as its economy began a blistering period of growth.

China also exported its hydropower know-how to developing countries further down the Mekong, especially Laos and Cambodia, where Chinese companies financed and built several projects.

The damming of the Mekong in recent decades has generated repeated concerns about environmental damage, social upheaval and the value of the economic trade-off.

Concerns about food security in the region moved back into the spotlight last month when research and consulting company Eyes on Earth Inc said satellite data showed China had above-average rainfall from May to October last year, but withheld the water behind its dams during the drought.

Brian Eyler, Southeast Asia program director of the Stimson Centre, a Washington-based think tank, described this as effectively “turning off the tap on the Mekong River.”

China and the MRC contested these findings, with Beijing saying it was unjustified to blame its dams for the drought.

In a statement on April 21, the MRC said “more scientific evidence was necessary to conclude that the 2019 drought was in large part caused by water storage in Upper Mekong dams.” It added that water flows “from China were higher than normal for the 2019 and 2020 dry seasons.”

The Mekong body said that while upstream dams had altered seasonal flows of the river, the drought was “due largely to very low rainfall during the wet season with a delayed arrival and earlier departure of monsoon rains, and an El Nino event.”

However, the commission said that more sharing of data and transparency was needed.

Harris Zainul, an analyst with the Institute of Strategic and International Studies in Malaysia, said the coronavirus pandemic could become a factor in the Mekong water disputes. Covid-19 has prompted lockdowns in many countries, which can block farmers from getting food to markets.

“If this were to happen, then countries, including those downstream of the Mekong, would be more sensitive towards the adverse effects arising out of lower water levels on the Mekong,” Harris said, adding that it could cause a public backlash against China in Mekong nations.

Beijing has said it works with downstream nations on water management through the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) established in 2015 by China, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam. China is the largest trading partner for the Mekong members.

At an LMC summit in February, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told his counterparts from the five Mekong states that Beijing had increased water outflows from the Lancang to mitigate the drought in the Mekong region.

China had suffered, too, he said. In Yunnan province, the local government said the region was hit by the worst drought in a decade, with average rainfall dropping 18%.

Pomun said part of the problem was a lack of transparency and cooperation from China, and that downstream villagers were often caught off guard by an unexpected release of water from China’s dams. When water was released without warning, crops on the riverbanks became flooded, he said.

Pomun said he was worried the coronavirus pandemic might worsen the situation as countries turned inward to protect their own natural resources and “keep the water to themselves more, to produce electricity for the economy, for their own country.”

A 79-year-old woman is recovering after surviving for three days when her son buried her alive because he grew resentful of living with her.

A man in northwest China has been detained after his 79-year-old mother was buried alive.

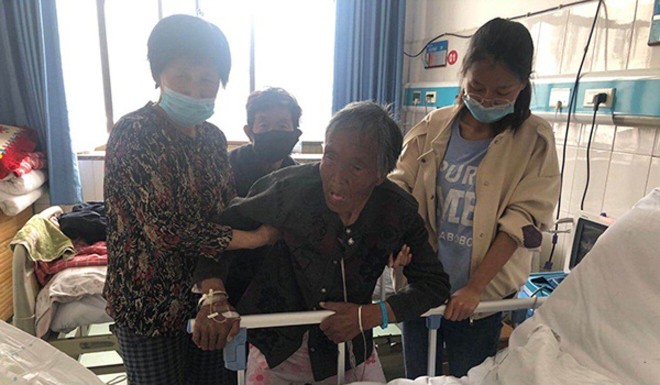

The woman, who was partially paralyzed, was rescued after three days and is in a stable condition in a hospital in Shaanxi province, police said.

Prosecutors in Jingbian county said the woman’s son, a 58-year-old identified only by his surname Ma, had been charged with attempted murder.

On Tuesday his wife told local police that Ma had taken the bedridden woman named Wang away on a cart and she had not returned home.

Police said the man had confessed to burying her in the woods and she was rescued later that day.

“Ma was there when police were digging up the two-meter deep grave. He didn’t say anything or respond when he saw his mother was still alive,” an unidentified Jingbian police official told news portal Thepaper.cn.

The website reported that Ma had been sent to live with his uncle after his father died, while his mother remarried and moved to Gansu province with her younger son when Ma was 12 years old.

She moved to Jingbian to live with her younger son when her second husband died.

Last year, she moved in with Ma when her health started to deteriorate.

Police said Ma began to resent her presence after she became bedridden after a fall last November. He complained that her incontinence was making the house smell bad.

A statement from the national health commission and the national office of elderly care called for severe punishment for the man and said he had “crossed the red line of law, morality and human relations.”

China’s jobs crisis could give leaders sleepless nights

China issues 11,380-word rebuttal to US coronavirus claims

Elderly woman survives three days after son buries her alive

Taiwan baseball league reopens stadiums to fans

Are China’s dams to blame for droughts in Southeast Asia?

For the first time in this season, the Taiwanese professional baseball league is allowing fans to watch games live. The stadiums will be limited to 1,000 fans per game, but it makes Taiwan one of the few places in the world hosting live sports.