Today, there are no clues as to the danger lurking outside my front door except for the eerie absence of people. Our lives are being restricted by a virus that is invisible to the naked eye, verging on abstraction, and yet it is terrifyingly real. Compare this to all the ways our lives are restricted by the many brutal rules, payments, and punishments of capitalism, which are now being revealed as actual fabrications that were subject to quick, substantive change all along—in other words, fake as hell.

The difference is: We can't change the fact that a virus is attacking the human species. We can change the fact that capitalists are attacking human life, too.

From arbitrary data caps being suspended by internet providers, to eviction bans, to suddenly-implemented protections for some workers, we are seeing that things we have long been told are impossible or unfeasible are suddenly OK. And as the estimates for how long our new world of "social distancing" will last stretch from weeks, to months, to a year, it's becoming more likely that when this is all over, we might not be able to return to "normal" even if we wanted to. But why would we want to?

It is clear that capitalism has failed us when people need support the most. The society we built on the premises of grift, waste, cruelty, and greed, is not one that can survive even a moderate disruption like a nasty virus without mass casualties and wrecked lives and bodies. What we urgently need, now and for the next crisis, is a society built more on resilience, solidarity, foresight, and compassion.

At this critical moment, when anything feels possible for good or for ill, we need to imagine how things can change for the better and to prevent future catastrophes. Almost nothing good comes to pass without mass struggle, and so it would be beyond naive to think that anything will happen "just" because it's plainly fucking obvious that it saves lives. Nobody knows what comes next, but it needs to be better than before. This is what it could look like. - Jordan Pearson

Free and universal healthcare

Last week, California Rep. Katie Porter questioned Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), on the costs that an uninsured American would face to get tested for coronavirus: $1,331. Over the course of five minutes, Porter made Redfield agree to invoke a federal regulation that would let him, and him alone, waive the cost of testing.

On March 13, the House passed legislation to make testing free anyway, but the regulation that Porter’s argument hinged on could be applied to waive the person cost of any disease for any intervention, including testing, treatment, and even transportation. It’s easy to think of worthy diseases or medical bills with costs that the CDC could unilaterally cover en masse, especially when such illnesses pose a greater risk to the community at large than to a given individual.

Inadequate testing has hampered America’s response to the pandemic, but countries with universal access to health care have gotten it right: South Korea, for example, has tested hundreds of thousands of people, while the U.S. is lagging behind. But the cost and availability of Covid-19 testing is just a symptom of underlying problems in the U.S. healthcare system that the coronavirus is now laying bare.

We’ve heard the refrain from one politician in particular, Senator Bernard Sanders, that healthcare is a basic human right: after the burden of the pandemic has lessened, we can and should scrutinize how our current system held up against single-payer systems in Britain or Australia, and then change it for good. Not only will this effect so much change in people's lives that American society may never be the same, but it will make us more resilient for the next crisis. - Maddie Bender

Abolish ICE and prisons

When ICE determines whether to detain or release immigrants and asylum seekers, it uses a rigged algorithm that only returns one result: Detain. Now, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the tens of thousands of people this purposely-broken system has sent to overcrowded detention facilities are facing a deadly virus that is about to spread rapidly through incarcerated populations across the U.S.

Groups like the immigrant rights organization Mijente are calling for ICE to immediately cease its raids and arrests, which are enabled by technology provided by companies such as Palantir, Dell, and Microsoft. Even now, the immigration agency has continued business as usual—arresting people outside hospitals, while shopping for food, and even while picking their kids up from school.

ICE is now a public health hazard

Forcing people into packed and unsanitary detention centers "increases the risk of infection, meaning ICE is now actively endangering public health in its single-minded mission to arrest undocumented immigrants,” reads an open letter that Mijente is sending to companies in light of the Covid-19 crisis. In other words, ICE is now a public health hazard.

This is not unique to the immigration agency. In prisons and jails—which are often overcrowded, unsanitary, and filled with people charged with non-violent crimes—disease spreads rapidly throughout incarcerated populations. On Wednesday, New York’s Riker’s Island jail reported that two people (an inmate and a prison guard) had tested positive for the virus. Advocates have been warning for decades that our entire carceral system is simply not built to promote the health and well-being of incarcerated people. And as medical experts have warned, what happens inside these facilities always quickly spreads to the surrounding communities.

State and federal authorities are under pressure to dramatically reduce jail and prison populations. Several states including Ohio and California have begun releasing hundreds of people to slow the spread of the disease, and some prosecutors have begun declining to prosecute non-violent offenses. But ultimately, as medical experts have noted over and over, the very structure and purpose of prisons and jails—and the cops and prosecutors who fill them with human beings—is antithetical to public health. Faced with an unprecedented health crisis, there has never been a more urgent time to donate to your local bail fund and demand that elected officials empty prison cells before they’re filled with bodies. - Janus Rose

Protect and empower labor

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, a few companies like Patagonia and R.E.I. have done the right thing and closed stores while continuing to pay workers in full. But millions of gig workers, contractors, temps, and fast food workers aren’t so lucky. Many companies, hoping to squeeze profits out of the pandemic stock-piling hysteria, have kept their doors open and refused to provide the most basic protections like paid sick days. Just to name a few: Amazon warehouse workers, Uber and Lyft drivers, Whole Foods team members, GameStop and BestBuy retail workers, all have not been offered paid sick leave (unless they test positive for Covid-19), and many have continued to go to work even if they’re sick or at high risk.

One of the biggest takeaways from the coronavirus pandemic has been that all workers need paid sick leave (which should not be conflated with paid time off or vacation days), paid leave for parents, and healthcare. Without these protections, everyone’s safety and health is put at risk, particularly the most vulnerable members of our society. Studies show that paying workers to stay home when they’re sick substantially reduces the spread of the flu.

Now more than ever is the time to imagine a better world for workers, which we’ve seen glimpses this week with the expansion of sick leave benefits. Unfortunately though, companies that have extended new benefits during the pandemic will roll those back when this comes to a close.

And so, real and lasting change for workers will need to take place on a systemic level with new benefits and protections for gig workers, franchise workers, contracted workers, temps, and the service industry workers. These can be brought about with a robust union movement (unionized workers are more likely to have paid leave, healthcare benefits, and lower deductibles than their non-union counterparts) and politicians who are willing to fight for these changes at every level of government. - Lauren Kaori Gurley

A healthier climate

At the start of the decade, many environmentalists called for 2020 to be the year where global carbon emissions definitively declined. Now, thanks to a global pandemic, that’s happening on a scale nobody could have imagined. And it feels like nothing to cheer.

China, the world’s largest carbon emitter, saw its carbon footprint shrink by a quarter in February as the nation took extreme measures to combat Covid-19, including significantly scaling back heavy industry. In hard-hit Italy, electricity demands and air pollution have both plummeted in recent weeks. The airline industry is in freefall and begging for bailouts.

There’s nothing good about reducing emissions like this. In fact, if the 2008-09 financial crash is any indicator, carbon could shoot right back up as soon as the crisis is over. As nations scramble to get their economies back on track, climate goals could fall by the wayside, especially if the price of oil remains low. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Instead of going back to business-as-usual, governments can put climate at the center of their economic recovery plans. Future stimulus packages can include tax credits for renewable energy and electric vehicles, as well as massive investments in green infrastructure like energy storage facilities and EV charging stations. Bailouts for polluters can include stipulations that they cut emissions in line with what the science says is needed to stave off climate catastrophe. We did a lot of this in 2009—and the result? The economy bounced back.

Right now, climate concerns are taking a back seat to the public health crisis. That’s a good thing. But as we start thinking about how to rebuild our lives in wake of this unprecedented upheaval, we’re going to have an opportunity to do so in a way that prevents far more deaths and suffering in the future. We’d be foolish not to take it. - Maddie Stone

Fast, accessible broadband

As millions of Americans hunker down to slow the spread of Covid-19, America’s broadband dysfunction is being laid bare. Many homebound Americans will find essential connectivity just out of reach, and efforts to roll back basic consumer protections have left Americans vulnerable to everything from privacy abuses to ISP billing fraud. In addition to treating their customers terribly, Covid-19 has exposed how their employees aren’t being treated much better. For decades, consumer groups, analysts, and telecom experts repeatedly warned that U.S. broadband networks were falling short. Recent studies suggest that some 42 million Americans lack access to broadband of any kind. U.S. consumers pay some of the highest rates for broadband in the developed world, and many simply can’t afford a broadband connection.

Meanwhile, U.S. broadband is rated mediocre at best at nearly every metric that matters thanks not only to a lack of broadband competition — but the well-lobbied politicians and revolving door regulators eager to defend the profitable status quo. Turn after turn, time after time, public welfare has taken a back seat to the quarterly earnings of telecom monopolies.

As America realizes broadband is an essential utility, everything from terrible U.S. broadband maps to the flimsy justification for broadband usage caps are being exposed as fantasy. Community owned and operated broadband networks, long demonized and even prohibited by law in many states, are looking better than ever in the wake of a nationwide crisis.

As with countless other sectors, the heartbreaking pandemic creates an opportunity to cast aside our illusions of exceptionalism and rebuild systems with an eye on affordability, accountability, and the common good. In the process shaking off monopolies that have stalled progress, gutted consumer protections, and left far too many disconnected and vulnerable. - Karl Bode

Smash the surveillance state

The United States used the September 11 attacks and the ever-present threat of "terrorism" more generally as a justification to roll out the surveillance state. This led to the passage of the Patriot Act, which included legal authority for the bulk surveillance of American citizens by the National Security Agency. It also led to the militarization of local and state police. Small towns and large cities all over the country now have tanks, for example. Before the coronavirus hit, we were just starting to take a hard look at rolling back some of the excesses of the Patriot Act.

This new pandemic must not be used as a reason to infringe on the civil liberties and privacy of millions of people. Already, we are seeing surveillance companies—many of which are untested—say that they can use their AI-powered cameras to detect those infected with coronavirus. Israel and Israeli telecoms are using a secret database of user location data to track those who are infected and those who might have come into contact with them, and American companies have considered following suit.

We cannot accept being constantly tracked and monitored by our governments and large corporations as the new normal

Technology of course must play a role in our response to coronavirus, and while we are in the midst of a crisis, we will probably have to accept things we wouldn't during more normal times. But after we're through to the other side, any surveillance that was used to slow the spread of the coronavirus must be rolled back. We cannot accept being constantly tracked and monitored by our governments and large corporations as the new normal. Decisions about how and when this technology is developed and deployed have to be made with the buy-in of those who will be surveilled, and these decisions must be made transparently. We should not, for example, hand huge government contracts to companies pitching untested, ethically dubious AI. Coming out of this crisis, there will be an opportunity to talk about the type of world we want to live in, and we must make clear that it's one that respects privacy. - Jason Koebler

Billionaire wealth

The last few years have shown how so many of society's problems are caused by the fact that individuals can amass incomprehensible private wealth that could, if deployed altruistically, alleviate the suffering and worry of literally millions of people basically overnight. And where are the rich now, during a public health crisis? They're sending people to work while jetting off to luxurious doomsday bunkers, getting Covid-19 tests while normal people can't, and also singing "Imagine" from bucolic getaways.

It is plainly obvious what needs to be done if we are going to have any sort of shot at a more resilient society: expropriate their wealth and put it to work. This isn't politics anymore, it's survival. - Jordan Pearson

Public transit that works

Transit agencies need money and they need it now. More than 220 elected officials, cities, and organizations signed a letter to Congress calling for almost $13 billion in emergency funding so transit agencies can keep providing service for essential workers even as ridership has plummeted by up to 90 percent. Congress giving money for transportation is nothing new, but the way in which it is given is critical to making sure it goes to the right place.

As I recently reported, Congress gives transit agencies money to build new things or buy new fleets of trains and buses, not to cover the costs of running service day to day. That's how the Great Recession stimulus worked, which is why nearly every city had to cut service and lay off bus drivers even as they hired construction workers and built new transit hubs. That approach won't cut it this time, and so it's time to scratch that rule.

It's also well past time to allow federal money to pay for the transit basics people care about: frequent, reliable service that goes where we need it to. A great many things are broken about the way the federal government funds public transit in this country. On the most fundamental level, there has never been a strategy formed about what goals that funding is supposed to accomplish (traffic reduction? The environment? Cost?) and how to measure whether those goals are being reached.

Admittedly, there are extremely difficult financial years ahead in an extremely difficult industry even during the best of times. Meanwhile, Congress is poised to prioritize bailing out airlines and the cruise industry before it takes a look at public transit, for reasons I think are bad and dumb.

There is opportunity, though: should Congress eventually meander its way to considering the fate of an industry that moves tens of millions of people every single day, it can start to ask some of those questions about what exactly they want our tax dollars to accomplish, and then actually do it. Should we actually bother to think about American public transit policy, we can make things better quickly. - Aaron Gordon

The right to repair

Coronavirus has exposed that America’s lack of right-to-repair laws are a sham. Before the virus, farmers couldn’t fix their own John Deere tractors and folks who fixed their own iPhones might wake up one day to find Apple had disabled the device.

Now, right-to-repair has become a matter of life and death. The U.S. doesn’t have enough ventilators to keep up with the demand COVID19 patients will present. To keep older ventilators and other crucial medical devices functioning, technicians need to be able to repair them. But, like iPhones, the medical device manufacturers use software to make repairs hard and do their best to keep repair manuals secret.

Even in the face of the crisis, manufacturers are keeping secrets and

making it hard to repair malfunctioning devices. To meet the demand for ventilators and spare parts, groups are gathering online to share recipes for DIY solutions. The third party repair company iFixit is building a database of manuals and repair information for medical devices. And physicians are sharing risky, but potentially life saving, techniques to hack ventilators to improve patient capacity. In Italy, device manufacturers are threatening to sue people who’ve 3D printed parts for medical devices used to treat medical device patients.

This isn’t the way things should be. People should be allowed to repair their own stuff, especially when that stuff is a life saving medical device needed during a pandemic. We shouldn’t rely on Elon Musk making ventilators to save us. We can save ourselves. Right-to-repair legislation is making progress across the United States. The virus has laid bare why it must be enshrined in law. - Matthew Gault

Science for the people

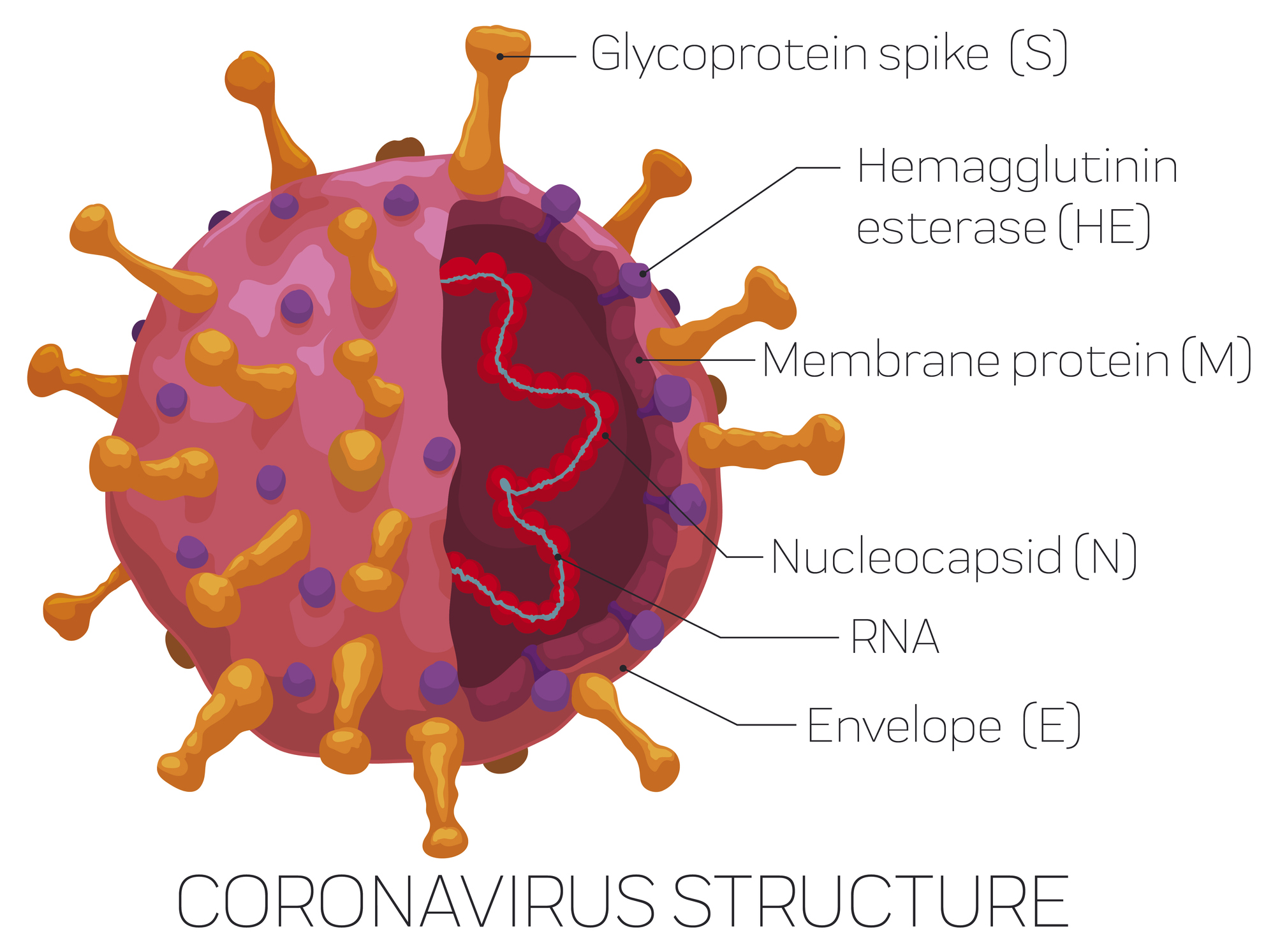

Covid-19 is not humanity’s first scrape with a deadly coronavirus. From 2002 to 2003, an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), also caused by a coronavirus, killed hundreds of people. It was a wake-up call to many scientists about the potential threat of a coronavirus strain to crescendo into a pandemic.

That’s why a team led by Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, had developed a SARS vaccine by 2016. The problem? No pharmaceutical or biotech companies were interested in funding trials of the vaccine in humans. The SARS outbreak had long since faded from the public’s attention, and there was no clear profit to be made from a vaccine that seemed to lack immediate demand.

We were caught flat-footed by a fixation on “innovation” and lack of public options

These structural funding gaps for neglected vaccines have now come back to bite us, with tragic consequences. Covid-19 is about 80 percent similar to SARS, as Hotez pointed out in his recent testimony to the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology of the United States House of Representatives, but we were caught flat-footed by a fixation on “innovation” and lack of public options. As it stands right now it will likely take at least 12 to 18 months to develop a vaccine that can safely be administered to the public.

“The peer review system heavily biases innovation so that sometimes—like, for instance, some of the vaccines that we used, which are pretty traditional recombinant protein technology—would not be of interest even though it’s important as a health product,” Hotez told me in a call. The only reason Hotez’s team eventually created the SARS vaccine was a generous government grant for biodefense, he said.

This unprecedented pandemic demands more aggressive investment in organizations such as nonprofit product development partnerships (PDPs), which can work on vaccines for overlooked diseases such as hookworms, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease—and yes, coronavirus. This will help the global medical community anticipate and stem future outbreaks of the scale and severity of Covid-19. - Becky Ferreira

This article originally appeared on VICE US.