When Frederick Winslow Taylor first sped up assembly lines and tested his idea of “scientific management” on factory workers in the early 1900s, it was, at least initially, a big hit. Taylor’s speed-ups, his techniques for breaking up work for more efficiency, were seen by workers as a way of getting the boss off their back. Workers were excited for more free time thanks to their improved efficiency, so the story goes.

But things didn’t turn out that way. Taylor’s speed-ups just meant working faster and making more stuff. Workplace productivity—as anyone who’s worked a service industry job will know—doesn’t mean you get off early. Taylor’s theories would eventually have gruelling impacts on the modern workplace. Those factory workers would organize unions to fight off the dehumanizing nightmare of time management; they would walk off the job and resist the stopwatch any way they could.

This is one of the facts I found out while procrastinating during a regular “Work Marathon” organized by a startup called Ultraworking—a four-day continuous video conference call for which freelancers pay $100USD to quietly sit and do work together in the hopes of becoming more productive, more conscientious digital workers.

The time management method is meant to develop what co-founder Kai Zau calls “mental ergonomics.” It’s virtual coworking in a 30 minutes on, 10 minute off “Work Cycle” spiced with a self-reflection spreadsheet. The startup claims that people who use Ultraworking’s methods have seen gains of two to four times their normal productivity. During these Marathon sessions, there’s no collective task or project. Instead, you pay money to enjoy the luxury of joining a large Zoom call where people are meant to keep each other focused. The stares of other people—what Ultraworking calls “social accountability”—are meant to replicate the discipline of the traditional workplace. You can come and go as you please during the Marathon, and nobody stays consistently online for four days, but the point is to log on for large chunks of time, in a state of productive bliss.

Just like the workers in Taylor’s factories, the devotees of Ultraworking see these Work Cycles as a transformative, liberatory tool to let the average freelancer take back control. It became, during the course of four days, my absolute nightmare vision of working from home. The question is: what would it mean if the devotees of Ultraworking were right? What if it really did mean a chance to change our everyday work life?

The first tip-off that something was weird with Ultraworking came from the fact that it started at 12:01 a.m.—at least in the East Coast time zone where I was participating. I was at my parent’s house at the time, staying in the room where I grew up. At 11:55 p.m. I squeezed my legs under a cramped desk surrounded by high school posters and old Christmas cards, and waited for the session to start. Because it was international, there was no regard for anyone’s time zone. This was the world of freelancing, and there’s no telling where the workday ends, and where another begins.

When the call finally went live and the moderator of the first session started speaking, I couldn’t hear him. My end of the video conference was glitching, and all I saw was his mouth moving, along with the faces of the other strangers participating in the session. When his audio came in, I realized that the mic on my end of the conference call was muted, and would remain muted for the duration of the Marathon. My screen was a Panopticon of bedrooms, coffee shops, and co-working spaces, with freelancers participating from around the world. An Ultraworking moderator ushered participants through a cycle of concentrated work followed by a 10-minute break, when we filled in a spreadsheet tracking tasks, distractions, and energy levels.

The first moderator was Sebastian Marshall, another co-founder of Ultraworking, who acts as a productivity guru, advising participants on tactics to boost their freelance efficiency. He speaks with the smug, wry tone of a young tech entrepreneur who’s found what he’s good at. As a freelance writer and something of a masochist, I spent the first cycle trying to work on an article pitch, firing up a Google doc and installing a Facebook newsfeed blocker before fucking off and getting distracted. I found myself hyper-aware of how I was optimising my time, fixating on the clock and trying to ignore the fact that it was the middle of the night.

During a 10 minute break period, the moderator enlisted a participant to talk about their work as a check-in. Over the course of the four days, we heard from a copywriter living their dream of work flexibility in South East Asia. We heard from someone trying to write a book, ploughing through dozens of pages a day—the most productive in their life, thanks to Ultraworking. We were instructed to drink water and to stay focused. Some people stood up during the breaks to do discreet jumping jacks and Wim Hof breathing exercises.

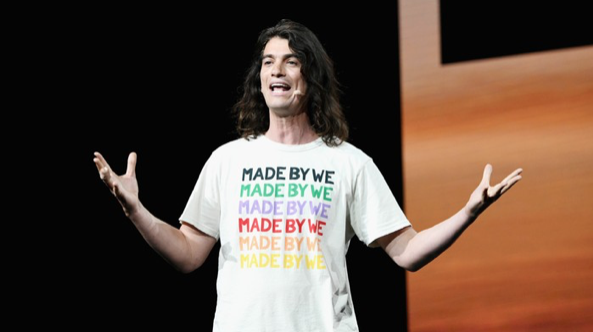

Ultraworking was founded by Zau and Marshall, who met while studying at university in Boston. The startup is part of a growing cottage industry of tech companies geared towards a freelance economy. There’s WeWork, the flailing coworking giant, Focusmate, which pairs you with a virtual work buddy and promise a “Community of Doers.” project management tools like Complice, and cutesy-sounding startups like 17Hats, which help with invoicing.

The tech world is rolling out tools—some flashy, some surprisingly basic—that try to offer the solitary worker a sense of managerial control once provided by conventional workplaces. Ultraworking fills the void of productivity and time management that used to be filled by simply working in a team, for an employer, with a clear sense of whether you’d still have work next week. In the process, they’ve laid stake to the future of work.

By Zau’s own account, very few of the people who use Ultraworking work a nine-to-five job, and very few of them have any semblance of what we would call a healthy work-life balance. Some people are reluctant about work, Zau explains, “on the other end of the spectrum there are people for whom work is equated with purpose, work is equated with meaning.” Zau is clearly in that second camp.

The spreadsheets that structure those 10-minute breaks are meant to make you think about the value and meaning in the work you do. The whole experience becomes, at points, debilitatingly self-conscious. I found myself constantly assessing each task, too self-aware of my progress to get anything done. I stared out my window for an entire 30-minute session just to see if anyone says anything. And—they don’t. You’re on your own, and it feels horrible.

But this is also where I start to realize that there’s a contradiction to these Work Cycle sessions. Between procrastination and self-monitoring, there’s a promise of something different, of a system which helps you work faster, and then be done with it. It’s a demand that political theorists on the left have started describing as “post-work.” And if you forget about the $100 signup fee, there are some compassionate measures in place for you, as a runner of the Marathon. If you fail to meet your cycle goal for three cycles in a row you’re prompted to choose an artificially easy goal to boost your confidence. Even as a small gesture, it points towards a different future for work—one where we can cut ourselves some slack, and feel less pressure to produce.

For Zau, Ultraworking is filling a demand made by remote working and precarious digital employment. He describes, in about 10 different ways, the Marxist definition of alienation using cool-guy tech lingo. “There's a lot of friction and a lot of confusion that comes from not knowing why you’re doing something, not knowing how today’s work ties with tomorrows work, ties with next week’s outcome, ties with everyone else’s work, ties with this North Star purpose of your company or your project.” This is exactly what’s driven demand for services like Ultraworking. Gamifying work, by giving it clear parameters and rewards is the way to turn it into something meaningful, Zau explains.

Selling productivity services to other businesses is the next obvious step in the path towards Ultraworking’s productivity utopia. On the company website, a section named “Enterprise” markets the product towards businesses hoping to make their team more productive—a prospect that opens the door to some rather serious digital workplace monitoring. WeWork, for its part, has openly admitted to tracking workers habits and amassing valuable data about how people use their coworking spaces. Zau says that while Ultraworking’s enterprise section hasn’t gotten much interest, business clients are something that the company is hoping to explore. The potential for workplace surveillance like this could undo a century of labour movement progress in a couple of distraction-free Work Cycles. During the Marathon the idea of this—of my employer being able to read over my Work Cycle questionnaires—feels deeply unsettling.

Mid-way through the four-day work Marathon, the structure breaks down, at least briefly. One of the workers invited to speak about their experience during a scheduled break used their time to talk about their struggles with mental health—manic episodes in particular, confessing that a fixation on work as a freelancer has contributed to those tendencies. Suddenly the neglected chat function on the side of the conference call filled with messages from other participants, who confess similar difficulties, with ADHD, depression, and a host of mental health conditions that intersect with their work life. Strangers start dropping in their emails into the chat, offering to discuss more offline. For a brief moment amid the work, the space fills with collective potential. When the 10-minute break is up, everyone puts down their heads and gets back to their respective tasks as if it never happened.

An Ultraworking early adopter, Mony Chhim is one of the participants who put his email into the chat during that break, offering to speak with people in case they wanted to talk about productivity and ADHD. Chhim is a digital marketer and copywriter living in Lisbon, and his workday is composed exclusively of 30 minute on, 10 minute off Work Cycles.

The method clicked for Chhim instantly. He cherishes Ultraworking’s “social accountability.” With the Work Cycles, his productivity shot up, and instead of taking on more work, his workday decreased in length. “I’m doing, on average, 8-10 cycles a day. That's less than five hours of actual work. And I still manage to have a really nice output,” he told me later. “Two times in my life I’ve tried to work myself to death. You do that—hustle your face off, because you feel like if you don’t then you aren’t an entrepreneur. And those two times I ended up miserable, depressed.”

Since then, he’s actively tried to change how he works. "The output is much more important than the number of hours,” Chhim explains. “Working 12 hours in a day, to me it’s really stupid, its just virtue signalling. Your clients don’t give a shit, they just want results.”

Chhim is sharp, and a bit bashful. From the video call his apartment looks balmy and coastal. Chhim was working as an engineer in a conventional workplace before he read Tim Ferris’ The 4-Hour Workweek, a book which set him on a new career path. The self-help guide is a classic in entrepreneur self-help circles, and Chhim’s bookshelf offers a short history of the thinking behind tech world productivity. He’s tried Benjamin Franklin’s famous workday routine (as seen on Lifehacker), the Pomodoro technique—an 80s time management technique offering basically the same structure as Ultraworking—and digital hygiene apps like Selfcontrol and Freedom. He wears an Oura ring to track activity and sleep. He’s a devotee of the Stoics, the school of ancient philosophy that’s taken off in Silicon Valley, and counts Viktor Frankl Man's Search for Meaning—a Peak Performance mainstay—among his favourite books.

Another big reference point? Ultraworking co-founder Sebastian Marshall’s book, as well as the blog he keeps. "Do you know about the Lights Spreadsheets?" Chhim asks me midway through our call. The Lights Spreadsheets is a task-management tool developed by Marshall, and both Zau and Chhim mention it to me when I interview them. It’s meant to encompass your entire life. Using the Lights Spreadsheet, Marshall has tracked every aspect of his life meticulously on a Google spreadsheet for the last three to four years. The very idea of work-life balance becomes just another item to tick off in the pursuit of higher productivity.

But when Chhim is talking about Marshall’s blogging about productivity, he seems incredibly genuine. As bleak as it may sound, the work productivity community have access to a set of tools that make it easier to get work done fast. It’s a special set of privileges and an education in its own right. For Chhim, these are the tools that have helped his mental health, and let him take more time for himself. As we advance towards a future with more freelancing, more remote work, and more automation, it's the possibility of redirecting time management away from entrepreneurial self-help and towards a collective reassessment of the meaning of work, that might be Ultraworking’s seed of liberation.

In the Marathon, we’re taught new parables of work: stories about a full month of endless productivity, phone call interruptions, big projects that are “shipped” in states of productive flow and intentionality. Like the first guinea pigs of modern productivity working in Taylor’s factory, the dream here is for everyday autonomy. There’s no celebration for the end of the marathon, the Ultraworking team informs us in the afternoon of the fourth day. The moderators don’t want people to stay online late. The last hours tick by, and then the Zoom call ends, leaving the screen black.

Follow Josh on Twitter.