9/11 -- Five Years Later: Tragedy forged a new path for many of us

-

Five years ago, Rodney Jong, 58, was a Boeing systems analyst who was setting up a new family and marriage counseling practice. "I'd been thinking about joining the Red Cross for a while," Jong said. "But I'd been putting it off. Then 9/11 happened, and I felt it was urgent." He signed up immediately, asking to be sent to New York City. lessFive years ago, Rodney Jong, 58, was a Boeing systems analyst who was setting up a new family and marriage counseling practice. "I'd been thinking about joining the Red Cross for a while," Jong said. "But I'd ... morePhoto: Gilbert W. Arias/Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Five years is a long time, and not so long at all.

It's long enough for a generation of babies born post-9/11 to be in their first days of kindergarten. Long enough for a generation to come of age and go to war.

It's not long enough to see a memorial rise where 2,749 fell. Nor long enough to erase the furtive glances skyward when a plane casts a shadow on your city.

But five years is time enough to change each of our lives in ways both visible and unseen, felt and imagined, subtle and profound.

The changes are there in the shoes we decide not to wear to the airport because they're too clumsy to remove, the way we think twice before we enter a word in Google, in the votes we cast.

They're there in reshuffled priorities and regained perspective, grievances let go, relationships forged.

For the individuals portrayed here, the cataclysm of 9/11 was the catalyst they never expected. A systems analyst turned to disaster relief; a student enlisted in the Army; a Muslim couple became ad-hoc ambassadors for their faith.

Still others became unwitting documentarians of a grim piece of history.

A few now question that history.

Here are some of their stories. For the rest, look within.

Something happened that day -- to each of us.

-- Carol Smith

It was time to follow a dream to help

For Rodney Jong, the calling came on 9/11.

A Boeing systems analyst by day, Jong was busy setting up a new family and marriage counseling practice on the side when the two planes plunged America into a new era.

"I'd been thinking about joining the Red Cross for a while," Jong said. "But I'd been putting it off. Then 9/11 happened, and I felt it was urgent."

Jong, 58, who lives in Redmond, was originally from Long Island, and the terrorist act struck close to his heart.

"Thirty years ago, my aunt and uncle had taken me to brunch at Windows on the World," the restaurant atop the World Trade Center. "It was very poignant for me to realize it was gone."

Jong, a licensed counselor, signed up immediately with the Red Cross, asking to be sent to New York City to work with those traumatized by the events. He wound up at the organization's national call center near Washington, D.C., for two weeks, starting that December.

Even months later, the trauma of those touched by the tragedy was palpable, he said. Some people just wanted to talk. Others were looking for psychiatric help. There were those who couldn't sleep without hearing bodies crashing down around them.

The events of 9/11 may have catalyzed Jong's call to action, but that first Red Cross experience sealed his commitment.

"I realized I wanted to continue to do this kind of thing -- to be available," he said. Three years ago, he retired from Boeing.

Jong, who still has his counseling practice, is now chairman of the disaster mental health committee for the Red Cross. Since 9/11 he has responded to disasters as near and individual as house fires in Seattle, and those that sweep through many lives, such as hurricanes. He went to Florida in 2004 after Hurricane Charlie rampaged through that state, and last year he helped relocate some of the Katrina survivors who arrived in Seattle.

"You hope every disaster is the last one, but there always is something else," he said.

His impression after each one? "There's always a feeling you haven't done enough."

But after 9/11, he realized that what matters is that you try.

"The thing that carries you forward," he said, "is that help is always needed."

-- Carol Smith

Couple next door as towers fell

For Tami Michaels, the attacks on the World Trade Center weren't something awful that happened on the other side of the country. It's part of her family history.

The Normandy Park woman saw the tragedy unfold, videotaped it -- even helped convict one of the terrorists.

Five years ago, Michaels, an interior designer, was staying with her husband at the Millennium Hilton, across the block from the Twin Towers.

The couple had visited the trade center on Sept. 10, 2001 -- dining at the glamorous Windows on the World restaurant atop Tower One.

"There were chandeliers, white tablecloths; it was so beautiful," Michaels recalled. "I think about it now and it reminds me of the Titanic."

The next morning, the couple were jarred awake by an explosion that knocked a water glass off their nightstand. She rushed to the window. Her husband, Guy Rosbrook, grabbed their video camera and began recording the grisly scene: people plunging to their deaths.

"We could see their gender, ethnicity, what people were wearing," Michaels said, "and then we saw them holding hands and jumping."

Moments later, another plane rammed the south tower. The blast blew Rosbrook across the room, fracturing his neck.

"We called our kids from the hotel room and told them we loved them," she said. "We stayed in the room knowing the (trade center) was going to collapse. It came directly at us."

The couple dived under a table, Rosbrook shielding her with his body. There was rumbling, falling debris, then silence. When they ventured outside, "there was just nothing," Michaels said. "It was just like the moon."

Word got out about their video, but despite lucrative offers the couple refused to sell.

"We just felt like it would be blood money, like it would be disrespectful to the people who lost their lives, not to mention their families," Michaels said.

The tape, and Michaels' testimony, were eventually used in the trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, who was sentenced to six life prison terms.

Michaels and Rosbrook plan to keep a copy of the tape in the family. They've written in their wills that it can never be sold. They plan to donate the original to the World Trade Center Memorial Foundation.

"We think it's important that people don't forget," she said.

Community rallies behind Muslims

Shortly after the 9/11 attacks, Shabbir and Ruqqy Bala wondered how the local community would react to the couple, one of the few Muslim families living in Snohomish.

The line at the door of their burger restaurant in Lake Stevens erased any apprehensions.

"That was our busiest weekend," Ruqqy recalled. "There were caring people asking, 'Are you OK?' That made me feel that we were accepted not only as Muslims, but as a family, too."

Five years later, the couple say they have become "ambassadors" for Muslims, explaining and sometimes defending their faith to the curious and the critical. They also condemn violent acts committed under the guise of Islam.

"Suicide is not allowed in Islam," said Ruqqy, 48, and those who blow up themselves and others do so to make a purely political point.

Such views are served up along with omelets, gourmet burgers and steaks at Boondocker's Cafe in Marysville, where the couple recently relocated their restaurant.

The clientele is mostly conservative and white. The Balas are liberal and emigrants from Pakistan, with Shabbir, a veteran restaurant manager, arriving in 1970 and Ruqqy following in 1983, when they married.

Their daughter, Sahar, 16, the lone Muslim in her junior class at Snohomish High School, said 9/11 placed a spotlight on her that has not dimmed.

"It gives me motivation to change people's minds," she said. "I definitely want people to be more accepting, to know and understand the differences between politics and religion."

Shabbir, 55, thinks the government has gone too far in targeting American followers of Islam. In the fight against terrorism, "the people you really want on your side is a Muslim," he said.

That's the case with the Balas' son, Faraz, 21, who is a second lieutenant at West Point after a stellar academic and athletic career at Snohomish High.

Faraz "looks at the Muslim world and believes we need to improve ourselves," Ruqqy said. She and her husband agree to a point, but say individual Muslims can do little to affect acts of a worldwide religion lacking an overriding hierarchy.

Since 9/11, Muslims are lumped together into "one group that's terrorizing the world," she said. "We are Muslims, but at the same time, we're individuals."

-- John Iwasaki

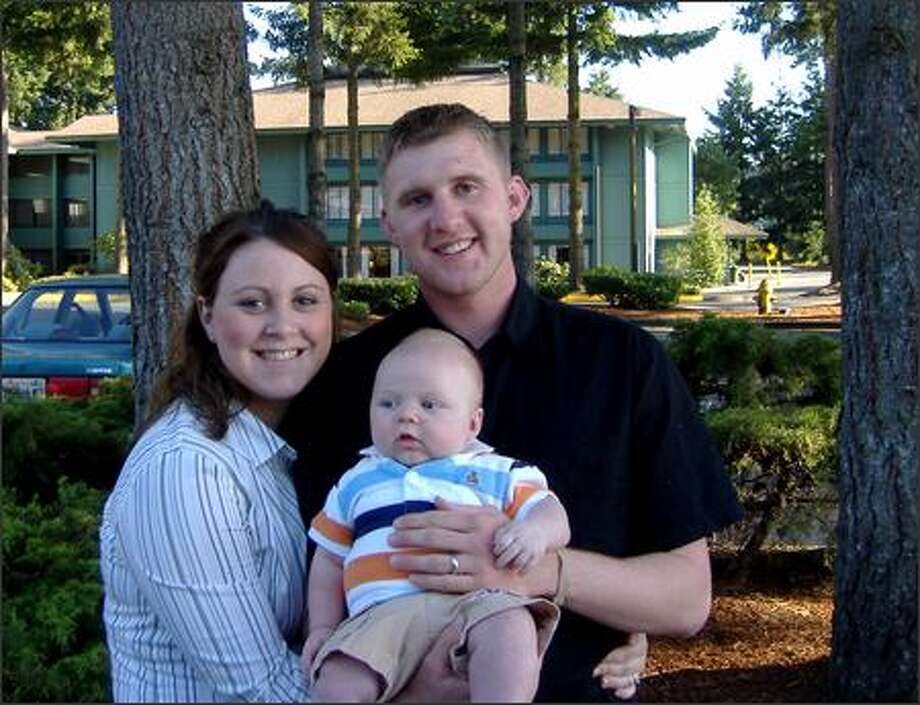

Attack a calling to high school student

When the World Trade Center crumbled, Ryan Bailey was in his high school art class in Racine, Wis.

"Someone came in and told us to turn on the television. They shut the school down and everybody went into the cafeteria and watched it for the rest of the day," Bailey, 21, recalled.

It was a life-defining moment. "Just then and there, I had to make a difference."

That meant enlisting in the war on terrorism. He joined the Army after graduating from Wilmot High School in 2003, several months after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

Bailey met his wife, Danielle, a Washingtonian, after arriving at Fort Lewis in 2004. The couple's first wedding anniversary passed in July with him in Iraq; she at home in University Place with their infant son, Jacob.

Bailey now has been in Iraq more than 40 days with Fort Lewis' Stryker Brigade. He's a signals support system specialist, meaning it's his job to make sure communications gear works right. He also pulls his share of security details on the streets of Mosul.

Bailey feels the progress being made in Iraq with U.S. military help is getting scant attention in the American media, preoccupied with death tolls.

"We're doing a lot to help the Iraqi people," he said. "There's a stadium we're helping rebuild for the community that has swimming pools and an activity center. Ramadan is coming up and we're donating toys."

The 9/11 anniversary may be big back home, but Bailey said it's hardly on his mind.

"We're mainly focused on the task at hand," he said.

-- Mike Barber

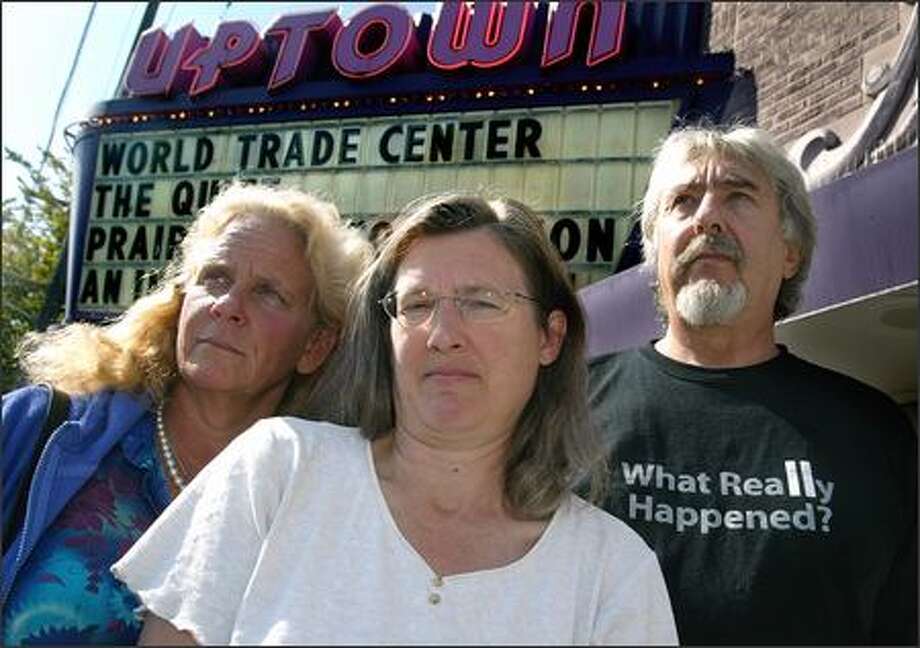

Conspiracy group searches for the truth

World Trade Center Building 7 hasn't ascended to Zapruder status. Not yet. This is good and bad, say members of the Seattle-based 911 Visibility Project.

On the upside, the 47-story skyscraper, which collapsed hours after the nearby Twin Towers fell, isn't conspiracy-theorist kitsch as is the iconic Kennedy assassination film shot by Abraham Zapruder.

On the downside, it's nowhere near as well-known even though Building 7, like that famous home movie, is similar bedrock for those trying to build a new truth while they tear down conventional belief. That the enemy isn't them; it's us.

"I first realized my reality shifted in 2004 when I attended a 9/11 presentation at a church in the U District," said Connie Eichenlaub, 52, a part-time adjunct college literature teacher and full-time member of the Visibility Project, which claims 300 subscribers.

"There were timeline problems in the initial government report. There was a distortion of reality."

Small, unvoiced concerns that had percolated since 9/11 grew to a full boil for Eichenlaub, as they did for retired former restaurant owner Ben Collet, 65 and for psychotherapist Kim Kerrigan, 55. The three now are part of the steering committee for the project, which is the Seattle chapter of 911truth.org, a leading proponent of alternative theories for 9/11.

Vastly simplified, the thinking goes that the military industrial complex needed a reason for a Mideast war. Many insufficiently explained 9/11 events, from the odd-shaped hole in the Pentagon to steel-framed Building 7's collapse from small fires -- it was not struck by a plane -- are what the group sees as evidence of a criminal cover-up.

So for this anniversary, they'll be out at busy overpasses with banners and they'll be leafleting 9/11-themed movies asking people to give their views a chance. They'll be greeted with supportive honks, mild bemusement and the occasional middle finger.

To some, they're "wing nuts," Eichenlaub offered.

"Bunch of kooks," Kerrigan said.

"But those people don't know," Collet added. "We've looked into it. The truth can be uncomfortable."

A recent Scripps-Howard survey showed that 36 percent of Americans now believe in some measure of government complicity in the attacks. One of the most popular Internet downloads ever is the 9/11 alternative theory documentary "Loose Change."

"Right after 9/11 you were seen as some card-carrying crazy if you thought the government did it," Kerrigan said. "Not anymore."

-- Mike Lewis

Dealing with death changed his life

The mountainous rubble at ground zero seemed to take on a life of its own. Trucks rolled in and out. Rescue workers dug tirelessly. Smoke rose from hidden fires.

"It seemed to be a living thing, because it was moving and changing as they were altering it," said Lou Smit, a 48-year- old Everett resident who arrived at the scene one day after 9/11.

Smit works in the Kitsap County Coroner's Office as coordinator of a new data-sharing system for death investigators. His work with the Network of Medicolegal Investigative Systems is what brought him to the World Trade Center ruins.

Even for someone who routinely deals with gruesome deaths, retrieving the remains of the 9/11 victims -- many of them police officers and firefighters -- took its toll. He'd find two left hands, two left feet, bodies compacted together.

He's still haunted by the imagery. And the stench of jet fuel and plumes of dust and ash.

"It was just overwhelming. You tasted it. You smelled it. You felt it. It was on you. Taking a shower didn't take it off you."

A former paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne who describes himself as a "hard-core guy's guy," Smit now finds himself crying inexplicably while watching movies on TV. The smell of gasoline at the service station triggers flashbacks.

"I'm a lot more emotional now. I can go from feeling fine to welling up and having tears in the blink of an eye, and I really don't have an explanation for it."

His wife, Alice, a Snohomish County corrections officer, said her husband frequently talks about 9/11 and is plagued by nightmares. "He hasn't really slept since he got back," she said.

Experiencing the devastation of 9/11 strengthened Smit's sense of duty -- and his commitment to improving post-disaster planning.

But he's also spending more time at home -- even coaching his 8-year-old son's football team.

"In a weird way," he said of the attacks five years ago, "it made me a better person."

-- Scott Gutierrez