Women live longer than men. In nearly all populations on Earth, women tend to live, on average, one to three years longer. Is it the way women and men live—their behaviors, what they eat, the risks they take, the social factors that influence them? Or is it hard-wired into their biology?

While nature vs. nurture debates about gender differences rage on, a study published on Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science sheds new light on why women tend to live longer. Biology, the researchers say, appears to be the primary reason. “Female [life expectancy] advantage stems from fundamental biological roots,” the study concludes, “and is influenced by socially and environmentally determined risks, opportunities, and resources.”

I spoke with lead author, Virginia Zarulli, assistant professor of biodemography at the Institute of Public Health at the University of Southern Denmark, to ask why.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Brigid Schulte: Before we get to the question of nature vs. nurture, have women always lived longer than men? What do we know from history?

Virginia Zarulli: We can trace this phenomenon quite well about 150 years back in time. We can see the differences in life expectancy for men and women started to widen at the beginning of the 20th century. It got wider until the 1970s and ’80s, and then it started to narrow a little bit. But even though it’s narrowing, women still live longer.

What happened in the 20th century that explains both the widening and shrinking of that gap?

Smoking. Smoking became really widespread among males of all social strata in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Virtually no women were smoking at that time. But during World War II and the 1950s, more women began to smoke. With smoking, it takes 20 to 30 years to see effects on a population level. So when women started smoking in the 1940s and ’50s, we began to see higher mortality rates from lung cancer in the ’70s and ’80s.

So that seems clearly a social, not biological factor. What did you look at in your new study that made you think biology was a more important reason for women’s longevity?

I wanted to look at extreme conditions—harsh famines, epidemics, slavery—and see if the female survival advantage applied even in cases of extreme emergencies, and whether that could help shed new light on whether there’s some innate ability that helps women live longer and survive better than men.

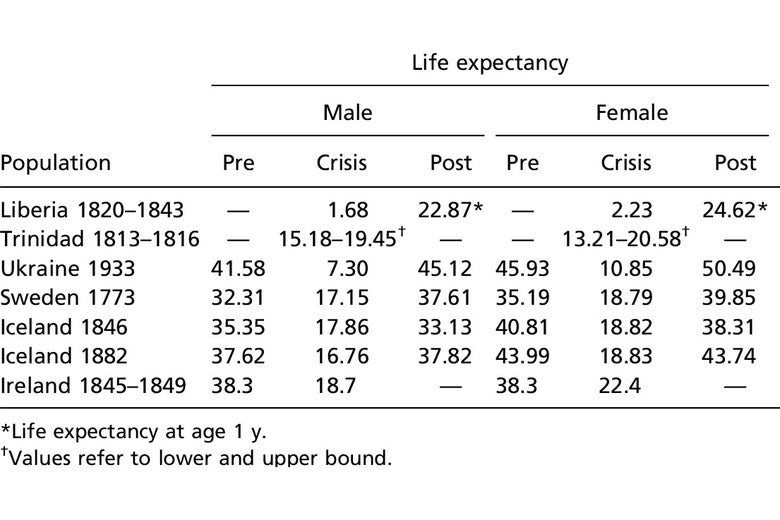

You studied seven different historical crises—devastating famines in Ireland, Iceland, Sweden, and the Ukraine in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries; the return of freed American slaves to Liberia between 1820 and 1834; and the lives of slaves forced to do punishing work on sugar plantations in Trinidad in 1813 through 1816. What did you find?

I found that, surprisingly, there was this very consistent pattern, that even under extreme conditions with higher mortality, women lived longer. Although life expectancy dropped for both men and women during these crises, it didn’t drop as much for women.

One of your charts shows that, for instance, in the Ukraine, prior to the famine of 1933, the average life expectancy for men was 41.58 years, which dropped to 7.3 during the crisis. For women, it was 45.93 years, which dropped to 10.85 during the crisis. Afterward, male life expectancy bounced back to 45.12, and women’s to 50.49.

And most importantly, in all cases but one, we found that the survival of women is higher than men at every age, from infancy and childhood to adulthood. We even looked at extreme age, when only 5 percent of the initial population has survived. Women are the ones who are able to endure the most.

You said there was one exception to this finding?

Yes, the partial exception was the case of the slaves on the sugar plantations in Trinidad. In that case, young adult males, 15 to 19, tended to survive longer than females. But that was clearly managed by human influence–the slave owners managing the conditions. We hypothesized that it could be that young male slaves had higher monetary value than females.

Yet when females entered child-bearing age, the pattern reversed, and the women lived a little longer. When males reached that age, they were heavily exploited, working up to 24- and 36-hour shifts with not even one day off, and had a higher mortality rate.

In all seven cases, when we looked at the survival in each age group, I was surprised that the biggest contributor to total life expectancy were infants, age 0 to 1. In other words, we found that baby girls living under those terrible conditions survived better than baby boys. In some cases, infant mortality made up 50 percent of the total gender gap. In other cases, 80 percent.

What does that tell us about whether women have some kind of biological advantage for long life?

For infants, it’s very unlikely that behavior plays a role in mortality. Boy and girl infants tend to act the same. It was this strong theme that pointed us to our conclusion that this life expectancy advantage for women is probably deeply biological. Parental attitude can influence survival, and we know from the literature that, at the time frame we were studying, if there was a sex preference, it usually was for boys. That’s still true in some places nowadays.

So, even though everything seems to point to an advantage for boys’ survival, and despite potential discrimination against girls, which was likely, the girls survived more.

Why do you think that is?

From the scientific literature, the two big factors appear to be hormonal differences and genetics. The most prominent hormones for women are estrogens, which tend to have protective effects against a broad set of diseases.

Your paper pointed out that women tend to have an advantage over men in the immune response to a host of bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and viral infectious diseases, like pulmonary tuberculosis, hepatitis A, rabies, and even seasonal flu. I had no idea.

And genetically, women are characterized by the double X chromosome. Men have XY chromosomes. So if women get a disease or mutation associated with the X chromosome, the other X chromosome can compensate for it, while men don’t have this possibility.

The other evidence is that men have more testosterone, which the literature shows increases the risk of contracting some diseases, infectious diseases, and also of reckless behavior. Testosterone brings men to do stupid things.

Ha. That reminds me that the Darwin Awards, given to people who die in the stupidest ways doing the stupidest things, and they tend to always be men.

It’s true that behavioral differences do affect life expectancy. Nowadays, women go to the doctor more often, they lead a healthier lifestyle, they drink less alcohol, they eat more vegetables and smoke less.

But we know that these social or behavioral differences aren’t the only explanation. Even in groups where the lifestyle is very similar—male and female nonsmokers, or cloistered monks and nuns, who both have very healthy lifestyles, there is still a big survival advantage for women. For instance, nuns live two and a half years longer than monks. While I’m not denying at all that social, behavioral, and cultural factors play an important role, all these pieces point to how biology appears to be at the root of it.

So how do you think your research will play into the larger question of whether men and women are biologically wired for certain roles in society or whether these roles are socially constructed and people’s fates could actually be more fluid?

Yes, of course, men and women have biological differences. But I don’t think we can apply the results of our study to anything other than survival. There is no evidence, as far as science is based, that women are hard-wired to do some things, and men to do others. As I said, behavioral differences observed among infants are minimal. But everything after that is probably culturally or socially acquired and modulated.

One more thing

You depend on Slate for sharp, distinctive coverage of the latest developments in politics and culture. Now we need to ask for your support.

Our work is more urgent than ever and is reaching more readers—but online advertising revenues don’t fully cover our costs, and we don’t have print subscribers to help keep us afloat. So we need your help. If you think Slate’s work matters, become a Slate Plus member. You’ll get exclusive members-only content and a suite of great benefits—and you’ll help secure Slate’s future.

Join Slate Plus