From 1527 to 1532, brothers Huáscar and Atahualpa fought over the Inca Empire. Their father, Inca Huayna Capac, had allowed each to rule a part of the Empire as regent during his reign: Huáscar in Cuzco and Atahualpa in Quito. When Huayna Capac and his heir apparent, Ninan Cuyuchi, died in 1527 (some sources say as early as 1525), Atahualpa and Huáscar went to war over who would succeed their father.

What neither man knew was that a far greater threat to the Empire was approaching: ruthless Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro.

Background of the Inca Civil War

In the Inca Empire, the word "Inca" meant "King," as opposed to words like Aztec which referred to a people or culture. Still, "Inca" is often used as a general term to refer to the ethnic group who lived in the Andes and residents of the Inca Empire in particular.

The Inca Emperors were considered to be divine, directly descended from the Sun. Their warlike culture had spread out from the Lake Titicaca area quickly, conquering one tribe and ethnic group after another to build a mighty Empire that spanned from Chile to southern Colombia and included vast swaths of present-day Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia.

Because the Royal Inca line was supposedly directly descended from the sun, it was unseemly for the Inca Emperors to "marry" anyone but their own sisters.

Numerous concubines, however, were allowed and the royal Incas tended to have many sons. In terms of succession, any son of an Inca Emperor would do: he did not have to be born to an Inca and his sister, nor did he have to be eldest. Often, brutal civil wars would break out upon the death of an Emperor as his sons fought for his throne: this produced much chaos but did result in a long line of strong, fierce, ruthless Inca lords that made the Empire strong and formidable.

This is exactly what happened in 1527. With the powerful Huayna Capac gone, Atahualpa and Huáscar apparently tried to rule jointly for a time, but were unable to do so and hostilities soon broke out.

The War of the Brothers

Huáscar ruled Cuzco, capital of the Inca Empire. He therefore commanded the loyalty of most of the people. Atahualpa, however, had the loyalty of the large Inca professional army and three outstanding generals: Chalcuchima, Quisquis and Rumiñahui. The large army had been in the north near Quito subjugating smaller tribes into the Empire when the war broke out.

At first, Huáscar made an attempt at capturing Quito, but the mighty army under Quisquis pushed him back. Atahualpa sent Chalcuchima and Quisquis after Cuzco and left Rumiñahui in Quito. The Cañari people, who inhabited the region of modern-day Cuenca to the south of Quito, allied with Huáscar. As Atahualpa's forces moved south, they punished the Cañari severely, devastating their lands and massacring many of the people. This act of vengeance would come back to haunt the Inca people later, as the Cañari would ally with conquistador Sebastián de Benalcázar when he marched on Quito.

In a desperate battle outside of Cuzco, Quisquis routed Huáscar's forces sometime in 1532 and captured Huáscar.

Atahualpa, delighted, moved south to take possession of his Empire.

Death of Huáscar

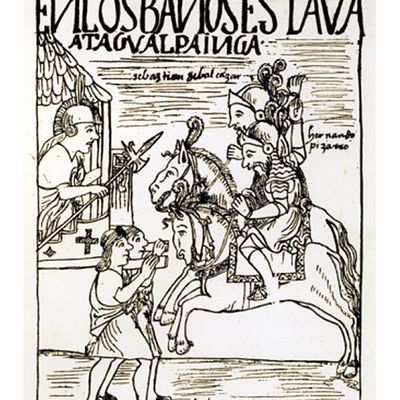

In November of 1532, Atahualpa was in the city of Cajamarca celebrating his victory over Huáscar when a group of 170 bedraggled foreigners arrived at the city: Spanish conquistadors under Francisco Pizarro. Atahualpa agreed to meet with the Spanish but his men were ambushed in the Cajamarca town square and Atahualpa was captured. This was the beginning of the end of the Inca Empire: with the Emperor in their power, no one dared attack the Spanish.

Atahualpa soon realized that the Spanish wanted gold and silver and arranged for a kingly ransom to be paid. Meanwhile, he was allowed to run his Empire from captivity. One of his first orders was the execution of Huáscar, who was butchered by his captors at Andamarca, not far from Cajamarca.

He ordered the execution when he was told by the Spanish that they wanted to see Huáscar. Fearing that his brother would make some sort of deal with the Spanish, Atahualpa ordered his death. Meanwhile, in Cuzco, Quisquis was executing all of the members of Huáscar's family and any nobles who had supported him.

Death of Atahualpa

Atahualpa had promised to fill a large room half full with gold and twice over with silver in order to secure his release, and in late 1532, messengers spread out to the far corners of the Empire to order his subjects to send gold and silver. As precious works of art poured into Cajamarca, they were melted down and sent to Spain.

In July of 1533 Pizarro and his men began hearing rumors that the mighty army of Rumiñahui, still back in Quito, had mobilized and was approaching with the goal of liberating Atahualpa. They panicked and executed Atahualpa on July 26, accusing him of "treachery." The rumors later proved to be false: Rumiñahui was still in Quito.

Legacy of the Civil War

There is no doubt that the civil war was one of the most crucial factors of the Spanish conquest of the Andes. The Inca Empire was a mighty one, featuring powerful armies, skilled generals, a strong economy and hard-working population. Had Huayna Capac still been in charge, the Spanish would have had a tough time of it. As it was, the Spanish were able to skillfully use the conflict to their advantage. After the death of Atahualpa, the Spanish were able to claim the title of "avengers" of ill-fated Huáscar and march into Cuzco as liberators.

The Empire had been sharply divided during the war, and by allying themselves to Huáscar's faction the Spanish were able to walk into Cuzco and loot whatever had been left behind after Atahualpa's ransom had been paid. General Quisquis eventually saw the danger posed by the Spanish and rebelled, but his revolt was put down. Rumiñahui bravely defended the north, fighting the invaders every step of the way, but superior Spanish military technology and tactics, along with allies including the Cañari, doomed the resistance from the start.

Even years after their deaths, the Spanish were using the Atahualpa-Huáscar civil war to their advantage. After the conquest of the Inca, many people back in Spain began wondering what Atahualpa had done to deserve being kidnapped and murdered by the Spanish, and why Pizarro had invaded Peru in the first place. Fortunately for the Spanish, Huáscar had been the elder of the brothers, which allowed the Spanish (who practiced primogeniture) to assert that Atahualpa had "usurped" his brother's throne and was therefore fair game for Spanish who only wanted to "set things right" and avenge poor Huáscar, who no Spaniard ever met. This smear campaign against Atahualpa was led by pro-conquest Spanish writers such as Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa.

The rivalry between Atahualpa and Huáscar survives to this day. Ask anyone from Quito about it and they'll tell you that Atahualpa was the legitimate one and Huáscar the usurper: they tell the story vice versa in Cuzco.

In Peru in the nineteenth century they christened a mighty new warship "Huáscar," whereas in Quito you can take in a fútbol game at the national stadium: "Estadio Olímpico Atahualpa."

Sources:

Hemming, John. The Conquest of the Inca London: Pan Books, 2004 (original 1970).

Herring, Hubert. A History of Latin America From the Beginnings to the Present. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962.

/Atahualpa-56a58ac53df78cf77288bab5.jpg)

/left_rail_image_history-58a22da068a0972917bfb5b7.png)