How a Major JRPG Wound Up Getting Totally Re-Written Months After Release

Some games get patches. Other games, like 'Ys VIII,' have scripts thrown out after fans rip it to pieces—and the publisher agrees with them.

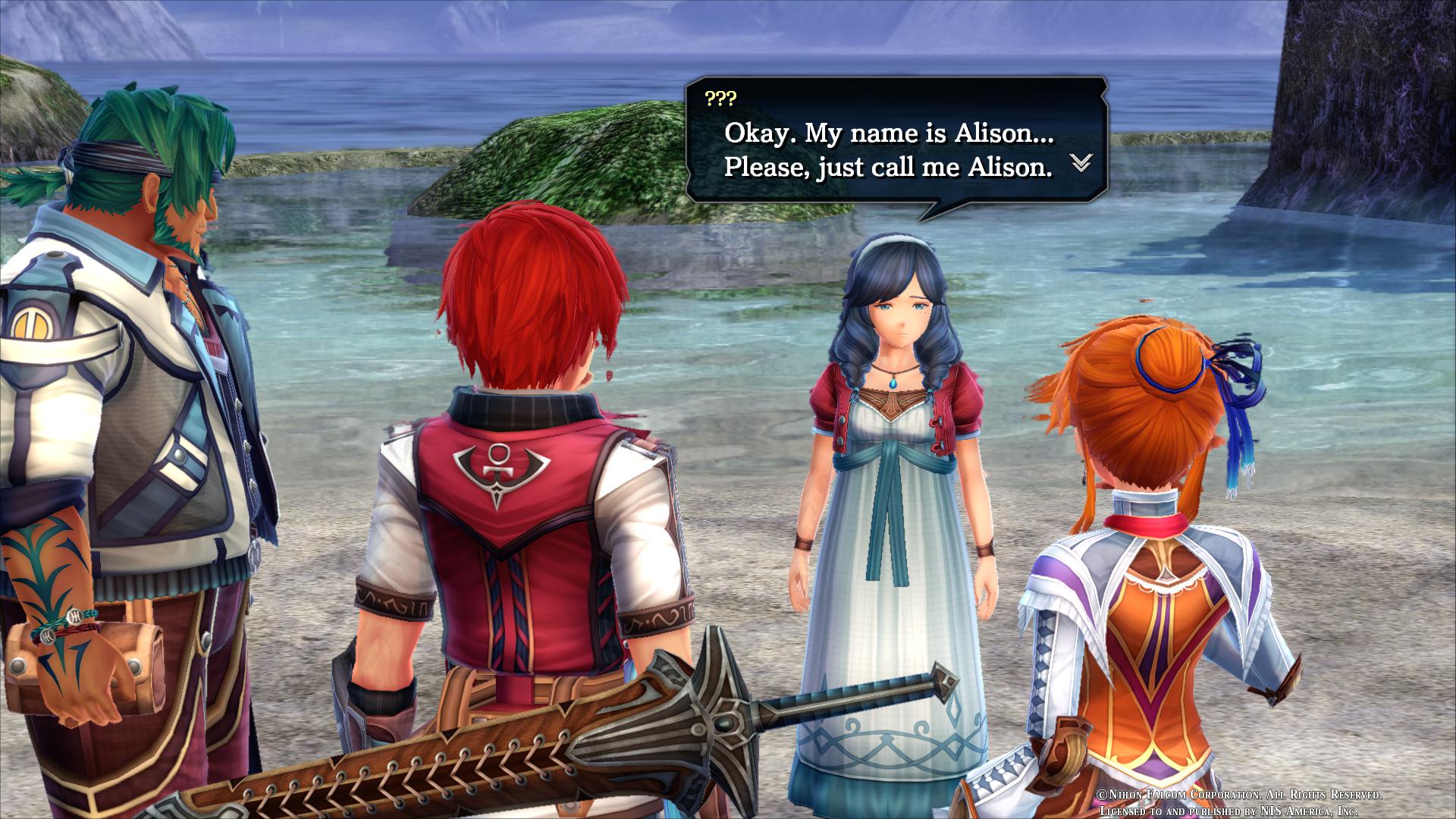

Image courtesy of NIS America

When a game ships out the door, it’s very common to see patches to address various issues players have. It’s quite another to see a company admit they screwed up a foundational element, and commit to re-doing it. But that’s exactly what happened when NIS America announced JRPG Ys VIII: Lacrimosa of Dana would get a complete re-retranslation, after weeks of critics and fans roasting its localization.

“It has come to my attention that the quality of the Ys VIII localization has not reached an acceptable level by our own standards, but most importantly by yours,” said NIS America president and CEO Takuro Yamashita in an unprecedented press release.

Though admirable NIS America would admit such a catastrophic failure and try to do right by fans, how did it happen in the first place? How does a game ship like that?

“As soon as a game comes out, you are just hitting refresh on OpenCritic and Metacritic and seeing what everybody has to say,” said NIS America senior associate producer Alan Costa, who’s heading up the game’s re-translation, during an interview recently. “Initially, when we'd hit sites and see the scores, we'd go ‘Oh, that's an eight. That's a nine! That's fantastic!’ But consistently, we saw reviewers saying ‘Great game, shame about that translation.’”

Ys VIII was a huge deal for NIS America, the Western branch of Japanese developer Nippon Ichi. As a studio focused on localizing Japanese games, ones made by their parent company and by others, landing the rights to the new, ambitious, and story-focused Ys helped put an exclamation point on a banner year for NIS America, who also localized Danganronpa V3 in 2017. Importantly, it was the first major Ys game translated by NIS America; previous entries had been handled by one of its competitors, XSEED. Fans were already nervous about the change.

Critics pointing out the localization was a huge red flag for NIS America. The company is used to fans taking issue with one decision or another—it’s the nature of working for a company specializing in localizing Japanese games—but it suggested the fan backlash would be worse. That proved true, as fans picked apart mistake after mistake.

Costa has been with NIS America for years, and once worked in the publisher’s localization trenches. In the leadup to Ys VIII’s release, he’d been traveling the world doing interviews and promotion with the person who’d written the story for Ys VIII, Nihon Falcom president Toshihiro Kondo. The localization team who’d handled many other games was in charge of finishing Ys. This was how the process worked.

But when Costa became aware of the reaction, he turned on the game.

“It became apparent pretty quickly that there was some major issues with the tone,” said Costa, “with the language used. From what I could tell, there was nothing that was translated incorrectly, it was just extremely dry.”

It seemed to be a bit more than that, as evidenced by a hardcore fan compiling a long list of problems with the localization, largely focusing on how awkward the writing comes across. While not gibberish, it didn’t exactly, uh, flow. One of the funnier examples is how the game translated an area called “Crevice of the Archeozoic Era.”

Calling it Acheozoic Big Hole is extremely funny, but probably not intentionally.

Costa quickly had a conversation with the head of NIS America, who roped the Japanese developers at Falcom. Falcom was aware of the script criticisms, but according to Costa, left the decision on what to do next to NIS America. Though some fans have conjectured Falcom pushed NIS America into the change, Costa called such theories “patently false.”

What does seem obvious, however, is how the choice to re-translate was fueled by the NIS America bottom line, for a variety of reasons. Conspiracy theories aside, it was their first time on Ys, and they screwed it up. Not only did that reflect poorly on the fans who’d supported them, but it could taint future business opportunities for NIS America. If they weren’t seen as a studio who could honor the games they were working on, they could lose projects. As more and more Japanese companies handle their own translations, the ripple effects may have hung around for years.

“That pie is getting smaller and smaller,” said Costa. “It's very important to us that we deliver on our promises and we deliver a high-product. It wasn't an ideal situation at all, but it did, at least, give us an opportunity to show our sincerity and our belief in a quality piece of work.”

Of course, that still doesn’t answer the core question: how’d it happen?

“Honestly speaking,” he said. “I don't know why.”

The re-translation has lead to a re-examination of the company’s internal processes, specifically addressing how nobody spoke up about problems with script along the way.

“What's really important is to really be true to what the creators wanted and to make sure it matches the tone of the game."

“I don't know if certain individuals didn't really understand their role within all of it," he said. "I don't even know if if the QA people thought ‘Maybe it's not my place. These guys translate, my job is to look for bugs and inconsistency and grammar and the grammar looks good. I'm not entirely sure. I don't think we can pinpoint one thing. If anything, it's all of those things.”

Nobody has been fired for what happened over Ys VII because Costa sees the problems as a collective failure, rather a single producer, localizer, or QA tester. Costa said NIS America is trying to shift the culture at the studio to a “see something, say something attitude,” even if that means highlighting problems in the work your friends did.

“When I was in localization,” he said, “you'd get in some really heated discussions about ‘No, I think this line is stupid, I don't think this character would say something like this and I think we really need to change it’ and the guy who wrote it would go ‘No, you're wrong, it makes perfect sense in this context.’ These conversations over one line could be five minutes, ten minutes. I want to say that maybe turned into ‘Do we really need to spend ten minutes on one line within a thousand-line script?’ That's what I'm guessing is one of the issues here.”

One problem, Costa theorized, was a lack of direct involvement by folks higher up, the people in a better position to make hard calls on a script’s direction. That’s why Costa, who spoke to me from a recording studio for Ys VIII’s re-translation, is taking such a hands-on approach with this project. That’s the plan for the future, as well.

An interesting wrinkle in this whole episode, though, is how it exposes rifts in how fans (and localizers) look at the role of localization. As I covered in a series of pieces for Kotaku—one about Fire Emblem, another about censorship—there are wildly differing philosophies on approach. Some fans demand a strict translation, which may result in a more robotic script, albeit more “faithful” to the original writing. Based on my interviews, most localizers try to adapt the script so it feels right in a new language, and if specific references, jokes, or memes don’t make sense, they change it.

“What's really important is to really be true to what the creators wanted and to make sure it matches the tone of the game,” he said.

To that end, while the original creators are tangentially involved in the process, by and large, the company doing localization is making the decisions. All of my reporting suggests this is how most localizations occurs: the creators step aside because they trust the people to do right by the original work. They aren’t hands-on.

“In my limited experience with the developers we've worked it,” said Costa, “they've been okay with leaving the localization up to us, under the idea that it's your market, your fanbase, you guys are Americans/European, so please localize it accordingly.”

Knowing that, and how seriously the studio appears to be taking the re-localization, I had to ask about one line in particular, a line involving, well, poop.

“Yeah, I ate and took a shit,” says Sahad. “I’m feeling great today, as usual!”

As it turns out, for all of the faults in Ys VIII’s script, this line was basically on-point.

“That line was very faithfully translated, actually,” laughed Costa. “I think it might be take a dump now? It might change. It's definitely within his character to say. He's a fisherman. He's kind of an uncouth guy, he lets these things slip. I'm pretty sure we changed it to dump, but a lot of times when you're in recording, the talent will read it in a certain way, or use a different word, and it sounds way better. I don't know how it'll turn out finally, but I don't think it's going to be shit in this next round. But, again, that was actually a very accurate translation.”

Shit? Dump? Don’t let anyone tell you localization isn’t full of hard choices.

Ys VIII's re-translation was expected before the end of the year, but was recently delayed into early 2018. The PC version will launch alongside it.

Follow Patrick on Twitter. If you have a tip or a story idea, drop him an email: patrick.klepek@vice.com.