The European Commission levied a record €2.42 billion ($2.73 billion) fine on Google yesterday for having “abused its market dominance as a search engine by giving an illegal advantage to another Google product, its comparison shopping service.” Commissioner Margrethe Vestager said in a press release announcing the decision:

“Google has come up with many innovative products and services that have made a difference to our lives. That’s a good thing. But Google’s strategy for its comparison shopping service wasn’t just about attracting customers by making its product better than those of its rivals. Instead, Google abused its market dominance as a search engine by promoting its own comparison shopping service in its search results, and demoting those of competitors.

“What Google has done is illegal under EU antitrust rules. It denied other companies the chance to compete on the merits and to innovate. And most importantly, it denied European consumers a genuine choice of services and the full benefits of innovation.”

It is tempting when these decisions come down to start with the ends: specifically, does the outcome in question agree with one’s pre-existing views on such matters as regulation generally, antitrust specifically, and even nationalism (or continentalism, as it were)? The means matter, though, especially in this decision: there are three meaningful questions in this case that cut to the heart of antitrust regulation of digital companies:

- What is a digital monopoly?

- What is the standard for determining illegal behavior?

- What constitutes a competitive product?

The European Commission’s decision was impressive on some of these questions, and very problematic on others; all sides of the antitrust debate should be wary of standing in resolute opposition or support.

What is a Digital Monopoly?

This is perhaps the most consequential aspect of this case, and I think the European Commission got it exactly right. Last year in Antitrust and Aggregation I explained why the unique dynamics of the Internet push towards dominant players that look very different from the monopolies of the past:

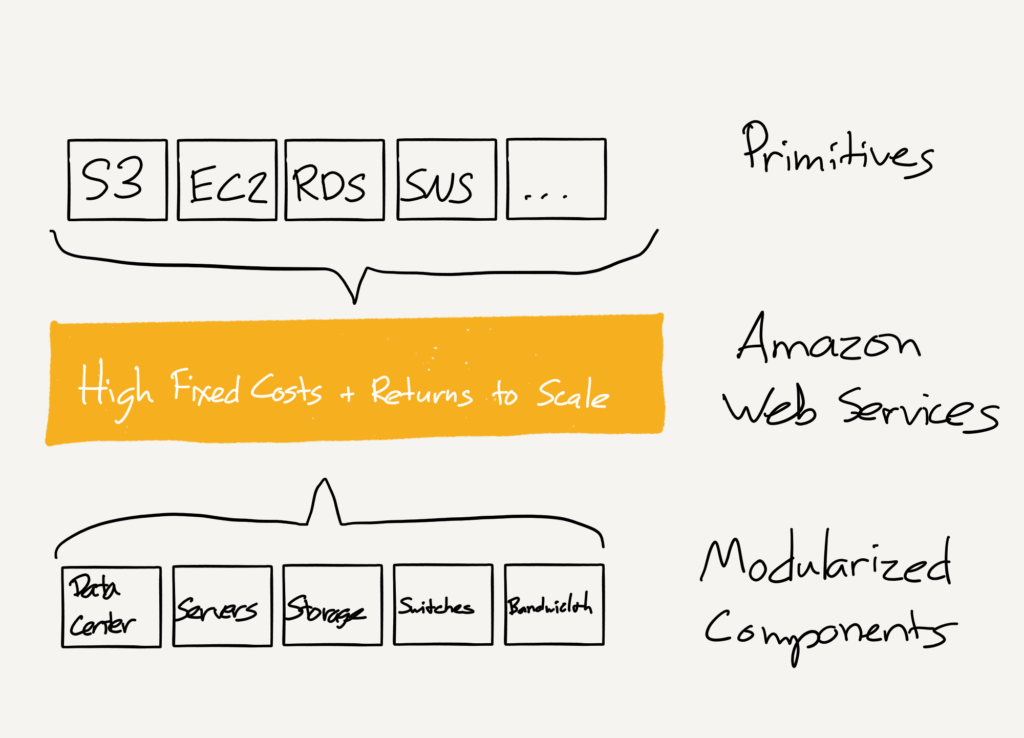

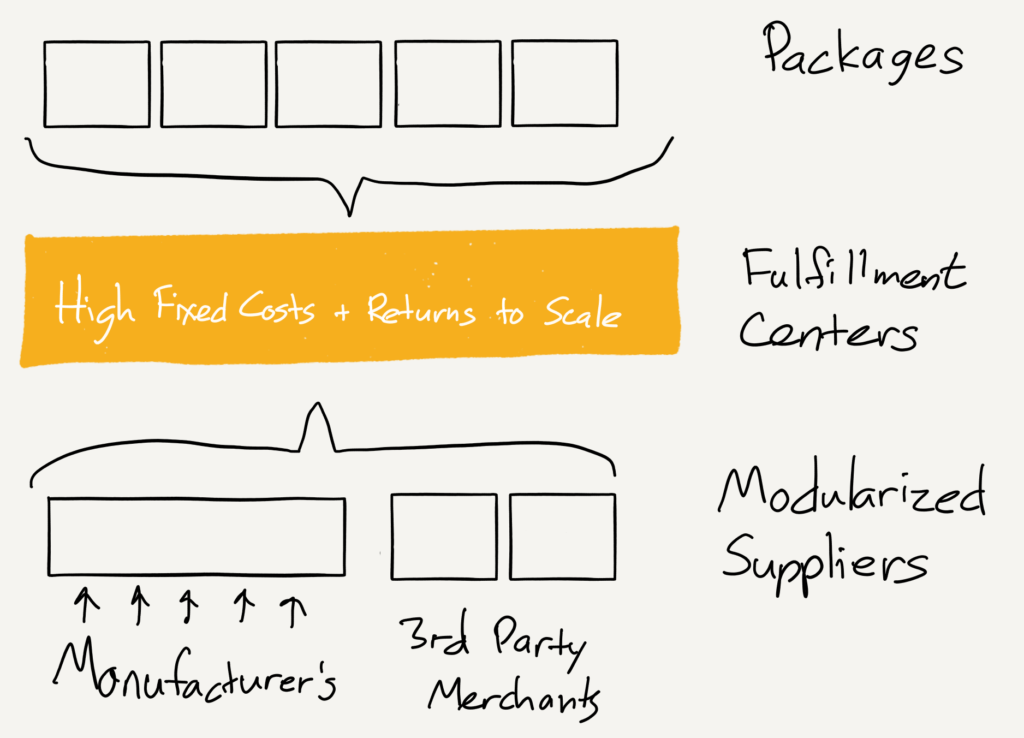

Aggregation Theory is about how business works in a world with zero distribution costs and zero transaction costs; consumers are attracted to an aggregator through the delivery of a superior experience, which attracts modular suppliers, which improves the experience and thus attracts more consumers, and thus more suppliers in the aforementioned virtuous cycle. It is a phenomenon seen across industries including search (Google and web pages), feeds (Facebook and content), shopping (Amazon and retail goods), video (Netflix/YouTube and content creators), transportation (Uber/Didi and drivers), and lodging (Airbnb and rooms, Booking/Expedia and hotels).

The first key antitrust implication of Aggregation Theory is that, thanks to these virtuous cycles, the big get bigger; indeed, all things being equal the equilibrium state in a market covered by Aggregation Theory is monopoly: one aggregator that has captured all of the consumers and all of the suppliers. This monopoly, though, is a lot different than the monopolies of yesteryear: aggregators aren’t limiting consumer choice by controlling supply (like oil) or distribution (like railroads) or infrastructure (like telephone wires); rather, consumers are self-selecting onto the Aggregator’s platform because it’s a better experience.

That bit about self-selection is the most obvious reason to critique this decision: how can Google have a monopoly when users — over 90% of the population in most European countries, according to the European Commission’s Factsheet — could choose to use another search engine simply by typing a URL, or opening another app? The Factsheet has the answer:

There are also high barriers to entry in these markets, in part because of network effects: the more consumers use a search engine, the more attractive it becomes to advertisers. The profits generated can then be used to attract even more consumers. Similarly, the data a search engine gathers about consumers can in turn be used to improve results.

This is exactly right, and in my view a real breakthrough in antitrust regulation. In the physical world, limited by scarcity, economic power comes from controlling supply; in the digital world, overwhelmed by abundance, economic power comes from controlling demand, and that control stems from a virtuous cycle that, for the reasons explained in the excerpt above, accrues to the dominant player in a space. In other words, to note that end users could go elsewhere is to ignore the reality that users are not dummies, and that network effects are the foundation of digital monopolies.

What is the Standard for Determining Illegal Behavior?

The United States and European Union have, at least since the Reagan Administration, differed on this point: the U.S. is primarily concerned with consumer welfare, and the primary proxy is price. In other words, as long as prices do not increase — or even better, decrease — there is, by definition, no illegal behavior.

The European Commission, on the other hand, is explicitly focused on competition: monopolistic behavior is presumed to be illegal if it restricts competitors which, in the theoretical long run, hurts consumers by restricting innovation. From the Factsheet:

Market dominance is, as such, not illegal under EU antitrust rules. However, dominant companies have a special responsibility not to abuse their powerful market position by restricting competition, either in the market where they are dominant or in separate markets. Otherwise, there would be a risk that a company once dominant in one market (even if this resulted from competition on the merits) would be able to use this market power to cement/further expand its dominance, or leverage it into separate markets…

As a result of Google’s illegal practices and the distortions to competition, Google’s comparison shopping service has made significant market share gains at the expense of rivals. This has deprived European consumers of the benefits of competition on the merits, namely genuine choice and innovation.

The European Commission approach, relative to the U.S. when it comes to determining illegality, has both pluses and minuses: the good thing is that it is an approach that is actually applicable to digital markets, particularly those monetized by advertising. Given the fact that Google is free for consumers, it is basically all but impossible for the company to be found guilty of antitrust behavior by the U.S., as the FTC determined a few years ago. The truth is that proxies are always problematic, including price, and there is no better example than the absurdity of the U.S. Justice Department successfully suing Apple for building a competitor to Amazon, the actual e-book monopolist.

On the other hand, isn’t consumer welfare the entire point? Sure, a narrow focus on price is perhaps a bad proxy, but if dominant services are winning by being better — which is my argument in Aggregation Theory — why should regulators busy themselves with demanding worse alternatives be given the right to succeed?

This is a point where many of those focused on the antitrust ends go wrong: in their crusade against big companies, they fail to grapple with the reality that on the Internet being big comes from being the best, leaving their arguments vulnerable to the critique that they are, in fact, anti-consumer, or at a minimum, anti-competence. To put it another way, in contrast to the previous point, regulators are treating people like dummies, assuming they can’t figure out how to find a competitive service, when in fact the truth is they don’t want to.

What Constitutes a Competitive Product?

This is by far the most concerning part of the European Commission’s decision, for two reasons.

First, if I search for a specific product, why would I not want to be shown that specific product? It frankly seems bizarre to argue that I would prefer to see links to shopping comparison sites; if that is what I wanted I would search for “Shopping Comparison Sites”, a request that Google is more than happy to fulfill:

The European Commission is effectively arguing that Google is wrong by virtue of fulfilling my search request explicitly; apparently they should read my mind and serve up an answer (a shopping comparison site) that is in fact different from what I am requesting (a product)?

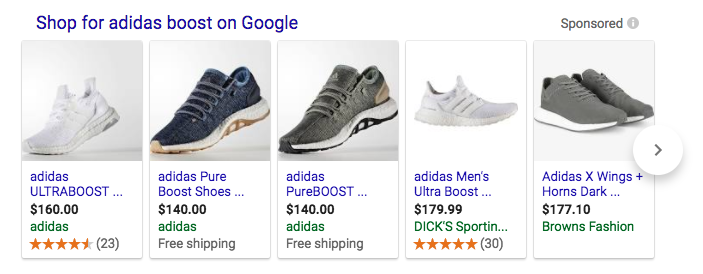

The second reason is even more problematic: “Google Shopping” is not actually a search product; it is an ad placement:

You can certainly argue that the tiny “Sponsored” label is bordering on dishonesty, but the fact remains that Google is being explicit about the fact that Google Shopping is a glorified ad unit. Does the European Commission honestly have a problem with that? The entire point of search advertising is to have the opportunity to put a result that might not otherwise rank in front of a user who has demonstrated intent.

The implications of saying this is monopolistic behavior goes to the very heart of Google’s business model: should Google not be allowed to sell advertising against search results for fear that it is ruining competition? Take travel sites: why shouldn’t Priceline sue Google for featuring ads for hotel booking sites above its own results? Why should Google be able to make any money at all?

This is the aspect of the European Commission’s decision that I have the biggest problem with. I agree that Google has a monopoly in search, but as the Commission itself notes that is not a crime; the reality of this ruling, though, is that making any money off that monopoly apparently is. And, by extension, those that blindly support this decision are agreeing that products that succeed by being better for users ought not be able to make money.

Long-time readers of Stratechery know that I have shifted my position on antitrust over time. At the end of the day, I tend to agree with the European Union that competition is an end worth pursuing in and of itself, and that antitrust regulation is fundamentally different from the sort of red tape that limits entrepreneurship. Indeed, it is directly opposed: red tape regulation entrenches incumbents and limits new entrants, while antitrust regulation limits incumbents and enables new entrants.

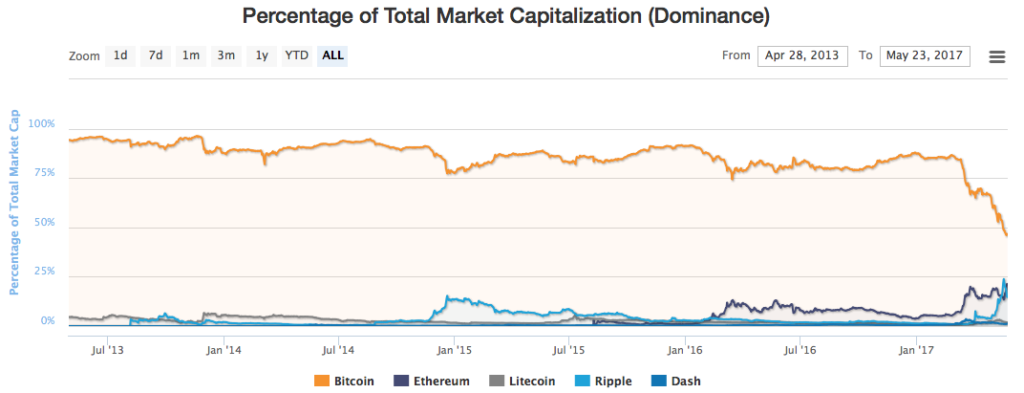

Moreover, I believe that Google has been a bad actor: the company’s scraping of content from Yelp, TripAdvisor, and Amazon was clearly anticompetitive, and a much better example of illegally favoring Google’s results over superior competition. And, more broadly, I started writing about the Google-Facebook duopoly in online advertising earlier than most; I have been building the case that that is where the problems of monopoly might most clearly be seen.

In short, I agree with the ends as far as the European Commission’s ruling is concerned: Google is a monopoly, and they act badly. In this case, though, I simply can not tolerate the means: I can not see any compelling case in which consumer welfare is better served by offering answers they didn’t actually ask for, and attacking an ad unit feels a lot more like an attempt to hurt a company as opposed to helping competition.

More broadly, antitrust advocates have to appreciate that, when it comes to digital monopolies, there is a very fine line to walk between opposing products that are better for consumers and promoting competition: I do think competition is ultimately pro-consumer, but simply presuming that “big” is bad when “big” comes from a superior customer experience is little more than a shortcut to political irrelevance.1

- In other words, wait for the Android case! More on the long-term repurcussions for Google tomorrow in the Daily Update [↩]