I’ll just say what we’re all thinking: studying takes too much time.

There are only 24 hours in a day, and naturally you’d like to use as many of them as possible for sleeping and, I don’t know, drawing pictures of robot bears or something. To achieve that goal, you need to find a method that lets you spend less time studying while retaining the same amount of information.

Here’s the solution: space out your studying. By introducing time intervals between study sessions, you can remember more – even if you spend fewer actual hours studying.

This is called spaced repetition, and it may be the most powerful technique in existence for improving your brain’s ability to recall what you study.

Today we’re going to dig into why it’s so powerful, and I’m going to show you how you can use it – both with paper flashcards and with apps. I’ll also show you the time intervals that have been scientifically proven to help you remember the most information.

But first, let’s look at the history behind this technique.

Spaced repetition leverages a memory phenomenon called the spacing effect, which describes how our brains learn more effectively when we space out our learning over time.

Here’s how Pierce J. Howard, the author of my least favorite book to haul into coffee shops – The Owner’s Manual for the Brain – explains it:

“Work involving higher mental functions, such as analysis and synthesis, needs to be spaced out to allow new neural connections to solidify. New learning drives out old learning when insufficient time intervenes.”

You can think of learning as being kind of like building a brick wall; if you stack the bricks up too quickly without letting the mortar between each layer solidify, you’re not going to end up with a very good wall. Spacing our your learning allows that “mental mortar” time to dry.

In fact, any kind of information benefits from this kind of spaced practice – which is something that we’ve known since the the birth of memory science over a 130 years ago.

Back in the late 1880’s, a psychologist named Herman Ebbinghaus became the first to systematically tackle the analysis of memory, and he did this by spending years memorizing lists of nonsensical syllables that he made up.

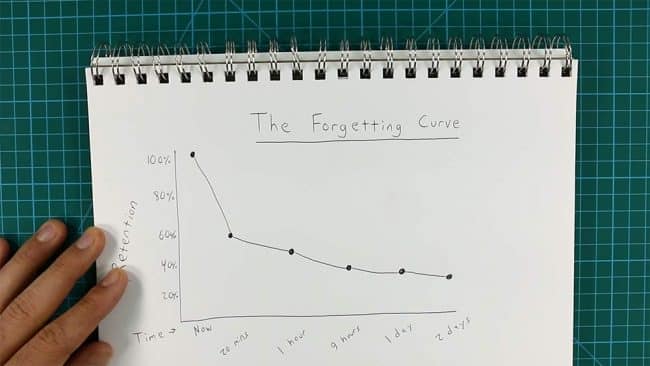

By meticulously recording his results – how many times he studied each list, the time intervals between his study sessions, and how much he was able to remember – Ebbinghaus was able to chart the rate at which memories “decay” over time. He showed this rate of decay in a graph called the Forgetting Curve.

The Forgetting Curve was incredibly influential to the field of memory science, but it’s also a bit misleading. It bolsters the idea that memories simply fade away over time. In fact, the truth is a bit more complicated.

For example: why do we sometimes remember mundane things – old street addresses, random conversations – that we haven’t thought about for years?

A New Theory of Forgetting

In his book How We Learn, author Benedict Carey describes the new theory of disuse (what he calls the “Forget to Learn” theory), which better explains why these memories seem to stick around, even as many others seemingly go the way of the dodo.

The first principle of this theory is that memories have two different strengths – storage strength and retrieval strength.

- Storage strength doesn’t fade over time. Once information has been acquired and the brain deems it to have met some threshold of importance, it stays stored. Storage strength can only increase through repeated recall or use.

- Retrieval strength – the ability to access the memory – does fade. It’s fickle, not as voluminous as storage strength, and needs regular maintenance.

As a result, “forgetting” is an accessibility problem. The memory exists in storage, but you can’t find it.

To make this theory easier to understand, I like to picture my brain as a huge library.

I’ve got plenty of shelf space, and when I add a new book, I can be sure that it’ll stay. My library is like the Svalbard Seed Vault of books; no thieves are getting in, temperature control is on lock, and the ventilation system is patrolled by trained attack praying mantises who deal with any sneaky moths.

With a library this size, though, the catalog needs lots of care and maintenance to stay useful. Over time, it’ll get messy and less useful unless I keep it organized. If I don’t, I won’t be able to find certain books anymore.

There’s no need to be overzealous about it, though. Like any maintenance process, there’s a point at which I’ll be “done” and can do no more good for now. Then I wait, things decay and become unorganized over time, and I come back and tidy them all up again.

This is the second principle of the “Forget to Learn” theory: The greater the drop in retrieval strength, the greater the increase in learning when the memory is accessed again. Here’s how Carey puts it:

“Some ‘breakdown’ must occur for us to strengthen learning when we revisit the material. Without a little forgetting, you get no benefit from further study. It is what allows learning to build, like an exercised muscle.”

Robert Bjork, one of the key contributors to the development of this theory, calls this the principle of desirable difficulty. And that brings us to the root of why spaced repetition is so powerful: using it helps you to maximize desirable difficulty – which, in turn, maximizes learning.

As it turns out, even Herman Ebbinghaus knew this. During his period of research, he found that he could perfectly recite a list of 12 nonsense syllables by doing 68 repetitions one day, then 7 the next.

However, with only 38 repetitions spaced out over three days, he could do just as well. A larger learning period, but a huge reduction in the raw amount of time spent actually studying.

As Ebbinghaus put it:

“With any considerable number of repetitions, a suitable distribution of them over a space of time is decidedly more advantageous than the massing of them at a single time.”

What are the Optimal Spaced Repetition Time Intervals?

Of course, we don’t just want a suitable distribution… we want the best distribution. After all, if spacing out your studying helps, there must be some optimal amount of space, right?

Piotr Wozniak – no relation to the Woz who built Apple’s first computers – spent a ton of time researching this question.

He eventually integrated what he found into the first spaced repetition computer software, which he called SuperMemo. The algorithm that determines SuperMemo’s intervals is quite complex, but here’s a simplified, nutshell-version of some of his first optimal intervals:

- First repetition: 1 day

- Second repetition: 7 days

- Third repetition: 16 days

- Fourth repetition: 35 days

A study published in 2008 with over 1,300 subjects also attempted to answer this question, but this time with respect to a given test date. What they found is that the optimal gap between the first and second study sessions increases in relation to how far away the test is.

Benedict Carey interpreted their data in How We Learn and came up with the following optimal intervals based on different test dates:

So if you’ve got a test coming up in a week, you should do your first session today, and then do the next session either tomorrow or the day after. I’d also recommend adding a 3rd session the day before the test.

It’s important to know that these gaps are approximate – as with pretty much everything in brain/memory science, it’s hard to make completely specific recommendations that will work for everyone. Still, these numbers are close, and you should take them into account when you’re creating exam study schedules.

Now, as I mentioned a minute ago, Piotr Wozniak implemented (and improved) his algorithm in SuperMemo. In fact, there are many spaced repetition apps out there that all have complicated algorithms – all of which are being regularly tweaked to become better and better.

So why tell you about the optimal intervals at all? Well, that’s because you can do spaced repetition the old-school way as well – with paper flash cards.

The Analog Spaced Repetition System

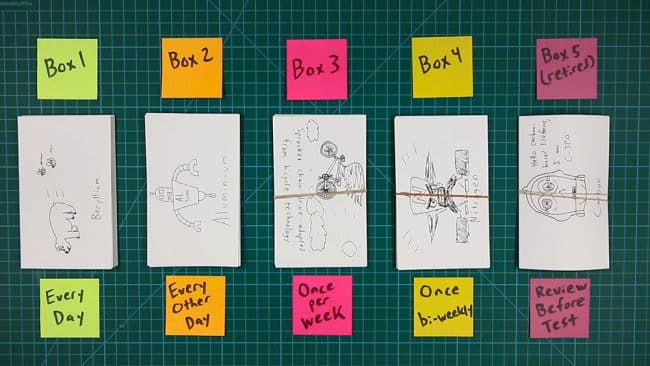

There are several ways of implementing a spaced repetition system into your flashcard studying, but one of the simplest and easiest to use is the Leitner system. Here’s how it works.

First, you decide on a number of “boxes” you want to use for your system. I have “boxes” in quotes because I don’t own little boxes and am just using rubber bands and labeled sticky notes instead – which actually makes the whole system more portable.

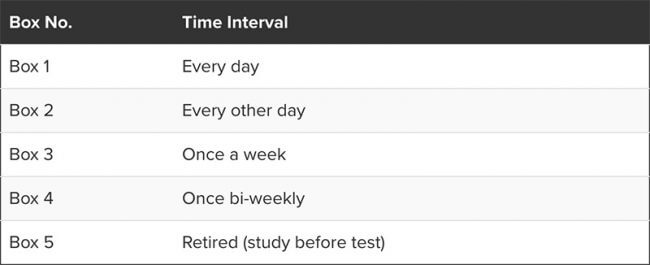

Each of your boxes represents a different study time interval. In a system with five boxes, a good set of intervals would be:

This schedule roughly follows the original algorithm developed by Piotr Wozniak, though I’ve made a couple of changes. First, I’ve stopped increasing the interval past two weeks to make the system work for realistic test preparation periods. Of course, you can always add more boxes if you want.

Second, I’ve introduced a “retired” box, which should hold cards that you definitely know. If you’re in college, you’re probably already super-busy with other things like trying to find an internship and coming up with money for textbooks, so I think it’s alright to consider those cards “known” – but I still think it’s a good idea to review them before a test.

Every card starts out in Box 1. When you get a card right, it graduates to the next box. If you get a card wrong, it goes all the way back to Box 1 – no matter where it was. In this way, you ensure that you’re studying the material that challenges you often.

After your boxes are set up, all you need to do is create recurring events on your calendar so you’ll know when to study each box. Pretty simple, right?

But, perhaps the analog lifestyle isn’t for you. Well, come along my computer-loving brethren. We can’t upload our consciousnesses and become robots yet, but we can at least use…

Spaced Repetition Apps!

The SRS (spaced repetition software) arena has a ton of contenders, including the aforementioned SuperMemo.

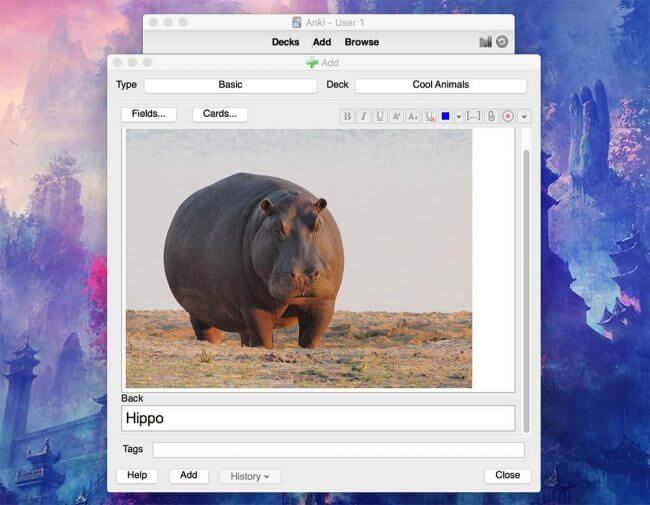

However, the most popular one these days is probably Anki, which I wrote about way back in the day and once again in my self-learning article.

Anki is popular for good reason; it has a huge community of people who share decks (though you’ll learn better by making your own), it’s insanely customizable, and there are free (with one caveat) apps for it on almost every platform, including

- Windows, OS X, Linux

- iPhone (see below)

- Android

There’s also a web client, so you can also do your studying straight from the browser.

The only caveat is that the iPhone version costs $25, which is most likely their way of letting people support the program since it’s free everywhere else. However, if you can’t afford that (it’s pretty steep for an app, I know), you can still use the web version in Mobile Safari.

Creating cards is easy, and you can add pretty much whatever type of media you like to them – which is excellent, since adding pictures can really help increase retention.

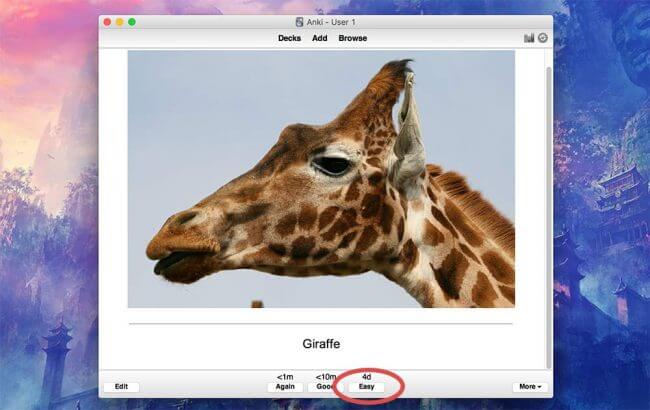

However, the real killer feature is the ability to rate your answers based on difficulty when you’re studying. After you turn a card over, you can let the program know how difficult it was to answer.

If you got it straight-up wrong, you’ll see it again during the same study session until you get it right. If you got it right, but it took a lot of work to dredge up the memory, you can tell Anki and it’ll make sure you see that card sooner rather than later. By contrast, cards that were a snap to remember won’t show up for a while longer.

This system of rating your answers really helps you get the most out of spaced repetition’s two main benefits:

- Maximizing the learning improvement through the spacing effect

- Studying more efficiently by not wasting time on cards you already know really well

There are tons of alternatives to Anki, though. The app I showed in my last video is called TinyCards, which was made by the team behind the Duolingo language learning app.

TinyCards is much simpler and, honestly, prettier than Anki. And in my opinion, the interface is awesome – it’s really easy to make new cards quickly, and the experience of studying them is really nice. Right now TinyCards is only on the iPhone, though the team is working on an Android app too.

Also on the iPhone is Flashcards Deluxe, which is, from what I’ve heard, possibly the best flash card app on iOS (it’s got an Android app too). Compared against TinyCards, it’s certainly more full-featured and customizable.

Other apps that support spaced repetition include:

- Memrise

- SuperMemo

- NimbleNotes – a cool hybrid that combines Evernote-like features with flash cards and spaced repetition

- Mnemosyne

- Eidetic

- Quizlet – though you need Quizlet’s paid subscription to access their spaced repetition features

If you don’t know where to start and just want a recommendation, I’ve personally always used Anki and really like it. If you have an iPhone, I’d say to also check out TinyCards if you like simplicity and don’t want to use AnkiWeb in the browser or pay for the app.

If you’re unable to see the video above, you can view it on YouTube.

Looking for More Study Tips?

If you enjoyed this article, you’ll also enjoy my free 100+ page book called 10 Steps to Earning Awesome Grades (While Studying Less).

The book covers topics like:

- Defeating procrastination

- Getting more out of your classes

- Taking great notes

- Reading your textbooks more efficiently

…and several more. It also has a lot of recommendations for tools and other resources that can make your studying easier.

If you’d like a free copy of the book, let me know where I should send it:

I’ll also keep you updated about new posts and videos that come out on this blog (they’ll be just as good as this one or better) 🙂

Video Notes

- How We Learn by Benedict Carey

- The Owner’s Manual for the Brain by Pierce J. Howard, Ph.D.

- Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology by Herman Ebbinghaus

- Original SuperMemo algorithm

- Latest SuperMemo algorithm – SM15

- What’s the best spaced repetition schedule? on Quora

- More detail on the Leitner system

- Details on Anki’s algorithm

Have something to say? Discuss this episode in the community!

If you liked this video, subscribe on YouTube to stay updated and get notified when new ones are out!

Images: bloomin’ onion, brick wall, giraffe, hippo

Leave a Reply

18 Comments on "How to Remember More of What You Learn with Spaced Repetition"

What is the first study gap actually for? I find it hard to believe that just because my test is three months away, after I study say, a GRE vocabulary word one day, I won’t have to review for two weeks just because the test is so far off. I’d think that I’d need more reviews in between so I don’t forget the word by two weeks later. There’s no way I’d ever get to remember because the reviews would be so friendly apart always. Having two weeks be the max makes more sense. Is that what it is? If not, how do I know what the max study gap should be also?

Hi, do you know a book that talks about more in depth about this method?

Thanks

how far out from exams do you start doing this ? I have 4 courses to study for and each one has 12 topics so that’s 48 distinct topics. I imagine some days I’d need to be doing multiple reviews . e.g. One day I may have to do four day 1 reviews and then 3 day 4 four reviews and 2 day 10 reviews (these will vary depending on when each topic has its day 1 review) .

I just need to work out how to incorporate them into my day. I

Every other day means you do it once every two days! So if you reviewed your ‘every other day’ flashcards today, you would NOT review them tomorrow, but you would review them again the day after that, and so on 🙂

Awesome article, thank you so much for everything that you are doing to benefit college students everywhere! You have helped me out many many times and I love everything you are doing! keep up the great work!

Hey! For this part that mentions optimum intervals, I don’t quite get whether the ‘days’ refers to days after first learning the information, or days since last reviewing it?

First repetition: 1 day

Second repetition: 7 days

Third repetition: 16 days

Fourth repetition: 35 days

So, for the fourth repitition, is it 35 days after the third repetition, or 35 days after having first learnt the info?

Thank you!

When I take notes, I put review dates in the margins. For example, if I take notes on March 13 the margin will have:

3/13

3/15

3/17

3/21

3/29

4/13

5/13

The first review day is 2 days after the lesson, the next is 4 days after the lesson, then 8 days, 16 days, 1 month, 2 months. As I review my notes, I check off the appropriate date. A study session begins with a review of my notebook. I look for the current date (or passed dated if unchecked) and review the notes that are due for review, checking off the date. I don’t have to review everything every day. Everything gets reviewed on the proper schedule.

Sorry, but what means “Every other day”? 🙂

Great idea, i’m going to use it 🙂

Every other day means you do it once every two days! So if you reviewed your ‘every other day’ flashcards today, you would NOT review them tomorrow, but you would review them again the day after that, and so on 🙂

I am now on the right track thanks to you. I am teaching Arabic speakers who have never been in school how to study for the Civics portion of the Citizenship test. 100 flash cards to memorize without any background knowledge or much English. I am teaching them ESL so that is covered but wow! – they get so tied to those 100 flash cards as a life and death matter. So with this spaced repetition and the boxes I have a technique that will make sense.

Hi Thomas,

This article is really well explained, thanks for taking the time to digging in the research. I ‘ve been studying about learning for some time now, mostly about learning skills that require motor skills, like sports or drawing. I’m trully interested in how our brains remember and learn theory vs action. In what you have experienced and found, how would you apply this spaced learning to practicing a physical skill? I see that you are into sports from your profile pic, have you used this method to teach yourself some of the theory for let’s say performance training goals or concepts, and then applied the physical aspect of “studying” (practice) these aspects of performance? I’m trying to figure out how to teach my art students to practice and learn better how to paint.

Thanks for the great work you deliver, I know it takes a lot of hours of researching and digging.

I have heard of this method used to teach touch typing, a physical skill. I have not tried it myself but I have heard that the results are phenomenal. Your question has inspired me. I might try a spaced repetition training schedule for juggling or doing a handstand.

Hi

Thanks for this I can see this been very useful. I am not an academic person and never really studied and school more just read the books and thought that was studying. Now as an adult I really struggle to study anything even though I want to learn as much as I can.

Seem to have a real fear of studying that I going to spend hours and hours reading, note taking and always fail practice test it just gets very depressing. I spent 7 plus years trying to study an IT technical exam which involved theory and hands-on practical stuff. Loved practical side and managed to grasp that but when it came to the theory and remembering that I was useless.

Only way I now seem to be able to pass any sort of exam is to do a day been taught then take the exam at the end of the day and even then its struggle.

I have no fear of exams or tests its more of the studying side and been able to retain the information.

Regards

Kev