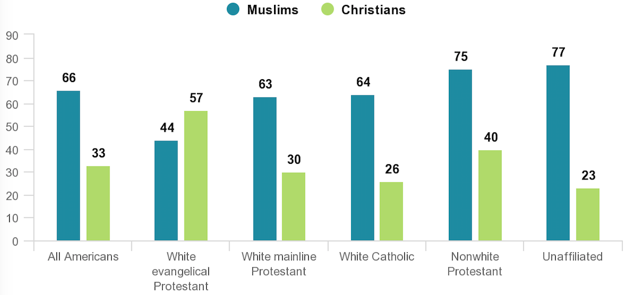

In February, pollsters at the Public Religion Research Institute asked Americans about their impressions of discrimination in the United States. Two religious groups were included on the list of those who might face bias: Christians and Muslims. Depending on who was answering, the responses were wildly different.

Overall, people were twice as likely to say Muslims face discrimination as they were to say the same thing about Christians. Democrats were four times more likely to see Muslim vs. Christian discrimination, and non-religious people more than three. White Catholics and white mainline Protestants were both in line with the American average: Each group was roughly twice as likely to say Muslims face discrimination compared to how they see the Christian experience.

The people who stuck out, whose perceptions were radically different from others in the survey, were white evangelical Protestants. Among this group, 57 percent said there’s a lot of discrimination against Christians in the U.S. today. Only 44 percent said the same thing about Muslims. They were the only religious group more likely to believe Christians face discrimination compared to Muslims.

White Evangelicals See More Discrimination Against Christians Than Muslims

Historical data suggests white evangelicals perceive even less discrimination against Muslims now than they did a few years ago—or before the election. When this question was asked in a December 2013 PRRI survey, 59 percent of white evangelicals said they think Muslims face a lot of discrimination. As late as last October, 56 percent said this was the case. As of February, that number had dropped by 12 percentage points. It’s possible that this finding is an anomaly—the sample size of white evangelicals in the February poll was smaller than in previous surveys—but it suggests a dramatic shift.

It’s difficult to quantify something as amorphous as “discrimination.” Perceptions like this might be shaped by everything from daily interactions to widely reported instances of assault, vandalism, or other intimidation motivated by bias. In terms of these kinds of hate crimes, Muslims fare far worse than Christians: 22 percent of religiously motivated crimes are against Muslims, compared to the 13.6 percent against Catholics, Protestants, Mormons, and other Christian denominations combined. Considering that Muslims are estimated to make up less than 1 percent of the American population, compared to Christians’ 70 percent, these numbers are even more stark. Jews, the group of people who are most likely to be the target of hate crimes, were not included in the PRRI survey as a category.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration used rhetoric and introduced policies that have made members of the Muslim community fearful. Progressives have labeled the recent executive order on immigration a “Muslim ban” because it targets predominantly Muslim countries. In his speeches, the president has emphasized the threat of “radical Islamic terrorism.” And Muslims have relatively little political power compared to other religious groups: Only two of the 535 members of Congress are part of the faith.

Other factors besides hate crimes and Trump’s policies have likely shaped white evangelicals’ perceptions. The questions about discrimination were included in a survey about LGBT issues, and for good reason: More than any other issue, changing cultural and legal norms around same-sex marriage and gender identity have raised objections from Christians. A number of court decisions from the last half decade or so may feed into white evangelicals’ perception that Christians face discrimination, including Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 Supreme Court ruling that legalized same-sex marriage.

That decision kicked off a wave of new challenges around religious conservatives’ right not to participate in gay wedding ceremonies, among other issues. Around the country, these cases are largely being resolved not in favor of religious plaintiffs: The Washington State Supreme Court recently ruled against a Christian florist who did not want to provide services at a gay couple’s wedding, for example.

These numbers cannot explain how different groups develop their perceptions of bigotry, whether it’s the media they consume, their geographic locations, or simply the communities they know best. But the survey does suggest something remarkable: White evangelicals perceive discrimination in America in vastly different terms than all other religious groups, including their minority peers.