At Sears, Eddie Lampert's Warring Divisions Model Adds to the Troubles

Every year the presidents of Sears Holdings’ many business units trudge across the company’s sprawling headquarters in Hoffman Estates, Ill., to a conference room in Building B, where they ask Eddie Lampert for money. The leaders have made these solitary treks since 2008, when Lampert, a reclusive hedge fund billionaire, splintered the company into more than 30 units. Each meeting starts quietly: When the executive arrives, Lampert’s top consiglieri are there, waiting around a U-shaped table, according to interviews with a half-dozen former employees who attended these sessions. An assistant walks in, turns on a screen on the opposite wall, and an image of Lampert flickers to life.

The Sears chairman, who lives in a $38 million mansion in South Florida and visits the campus no more than twice a year (he hates flying), is usually staring at his computer when the camera goes live, according to attendees.

The executive in the hot seat will begin clicking through a PowerPoint presentation meant to impress. Often he’ll boast an overly ambitious target—“We can definitely grow 20 percent this year!”—without so much as a glance from Lampert, 50, whose preference is to peck out e-mails or scroll through a spreadsheet during the talks. Not until the executive makes a mistake does the Sears chief look up, unleashing a torrent of questions that can go on for hours.

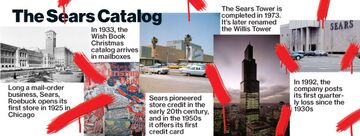

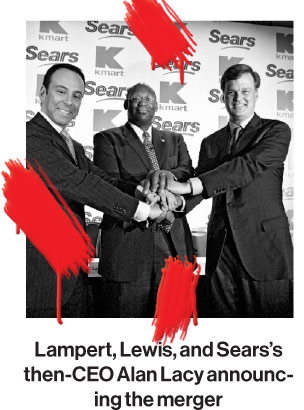

In January, eight years after Lampert masterminded Kmart’s $12 billion buyout of Sears in 2005, the board appointed him chief executive officer of the 120-year-old retailer. The company had gone through four CEOs since the merger, yet former executives say Lampert has long been running the show. Since the takeover, Sears Holdings’ sales have dropped from $49.1 billion to $39.9 billion, and its stock has sunk 64 percent. Its cash recently fell to a 10-year low. Although it has plenty of assets to unload before bankruptcy looms, the odds of a turnaround grow longer every quarter. “The way it’s being managed, it doesn’t work,” says Mary Ross Gilbert, a managing director at investment bank Imperial Capital. “They’re going to continue to deteriorate.”

Plagued by the realities threatening many retail stores, Sears also faces a unique problem: Lampert. Many of its troubles can be traced to an organizational model the chairman implemented five years ago, an idea he has said will save the company. Lampert runs Sears like a hedge fund portfolio, with dozens of autonomous businesses competing for his attention and money. An outspoken advocate of free-market economics and fan of the novelist Ayn Rand, he created the model because he expected the invisible hand of the market to drive better results. If the company’s leaders were told to act selfishly, he argued, they would run their divisions in a rational manner, boosting overall performance.

Instead, the divisions turned against each other—and Sears and Kmart, the overarching brands, suffered. Interviews with more than 40 former executives, many of whom sat at the highest levels of the company, paint a picture of a business that’s ravaged by infighting as its divisions battle over fewer resources. (Many declined to go on the record for a variety of reasons, including fear of angering Lampert.) Shaunak Dave, a former executive who left in 2012 and is now at sports marketing agency Revolution, says the model created a “warring tribes” culture. “If you were in a different business unit, we were in two competing companies,” he says. “Cooperation and collaboration aren’t there.”

Although Lampert is notoriously media-averse, he agreed to answer questions about Sears’s organizational model via e-mail. “Decentralized systems and structures work better than centralized ones because they produce better information over time,” Lampert writes. “The downside is that, to some, it appears messier than centralized systems.” Lampert adds that the structure enables him to evaluate the individual parts of Sears, so he can collect “significantly better information and drive decision-making and accountability at a more appropriate level.”

Lampert created the model because he wanted deeper data, which he could use to analyze the company’s assets. It’s why he hired Paul DePodesta, the Harvard-educated statistician immortalized by Michael Lewis in his book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game, to join Sears’s board. He wanted to use nontraditional metrics to gain an edge, like DePodesta did for the Oakland Athletics in Moneyball and is trying to repeat in his current job with the New York Mets. Only so far, Lampert’s experiment resembles a different book: The Hunger Games.

Lampert’s story is legendary on Wall Street. After his father’s death at 47 from a heart attack, he worked in warehouses as a teenager. He studied at Yale, joined Goldman Sachs, then launched his own fund, ESL Investments, in his twenties. Thanks to prescient investments in companies such as IBM and AutoNation, he was a billionaire by age 41.

His notoriety grew in the early 2000s, when he launched a takeover of bankrupt retailer Kmart. During negotiations, Lampert was kidnapped from a parking garage in Greenwich, Conn., and held for two days. Shortly after his captors released him, he jumped back into dealmaking. Two years later he used the retailer as a vehicle to buy Sears, which was also floundering at the time.

At first, Lampert’s reputation convinced investors that he could turn both companies around. “He’s lightning fast,” says Dan Levine, a former analyst at ESL who also worked at Sears. “He’s razor-sharp smart; he’s very direct.”

Many who worked for Lampert describe him as brilliant. They add, though, that he can overestimate his own abilities. Although the hedge funder lacked retail experience, he often lectured veterans on the industry’s nuances. Three former employees say Lampert compared himself to John Wooden, the lauded UCLA basketball coach, citing Wooden’s proclamation that he had to teach players how to put on their shoes before he could teach them to play basketball.

Lampert loathes focus groups, and certain jargon, like “vendor,” drives him nuts. In an instance that’s become famous at Sears, former brands chief Guenther Trieb once used the word “consumer” while giving a presentation. Lampert interrupted Trieb and delivered a lengthy lecture on why he should use the word “customer” instead.

While he often clashed with retail veterans, Lampert got along better with businessmen from finance and technology. “[Lampert] valued the outsider view,” says Bill Kenney, a former vice president who now runs his own consultancy. “He tends to bring people into the company who don’t have a lot of retail experience.” In addition to Moneyball’s DePodesta, Lampert hired Steven Levitt, the co-author of Freakonomics and co-founder of Chicago-based research firm the Greatest Good, as a consultant.

The newly merged Sears Holdings thrived at first, boosted by aggressive cost-cutting. By 2007, though, profits had declined 45 percent. Lampert began working on an ambitious restructuring plan, enlisting the help of Dev Mukherjee, a charismatic ex-IBM executive. At the time, Sears was organized like a classic retailer. Department heads ran their own product lines, but they all worked for the same merchandising and marketing leaders and toward the same financial goals. At the top of the pyramid sat Lampert, who ran meetings from his homes in Greenwich, Aspen, Colo., and, recently, Florida. Several former Sears executives nicknamed him The Wizard of Oz.

To boost “visibility and accountability,” Lampert explained in a letter to investors, he divided the company into more than 30 business units, including product-based divisions (apparel, tools, appliances), support functions (human resources, IT), brands (Kenmore appliances, Craftsman tools, DieHard batteries), and units focused on e-commerce and real estate. Under the new scheme, each business unit had its own president, chief marketing officer, board of directors, and, most important, its own profit-and-loss statement.

Large technology companies and industrial conglomerates such as General Electric also take a decentralized approach. But retailers tend to favor an integrated model. That way, different divisions can be compelled to make sacrifices, such as discounting goods, to attract shoppers to stores. The Sears model “isn’t a management strategy that’s employed in a lot of places,” says Gary Schettino, a former vice president who left Sears last year for a shopping site. “It’s dysfunctionality at the highest level, because there isn’t a retail expert in charge.”

Executives close to Lampert expressed concerns that the new model would create rival factions. The chairman responded by comparing Sears to Greenwich Avenue, the ritzy shopping district near his home in Connecticut. There, he argued, the individual stores are run separately, but shoppers view them collectively as a premier brand. Why wouldn’t the same logic apply to Sears?

When Mukherjee unveiled the plan in January 2008, many Sears executives were befuddled. From then on, they were told, the units would act like autonomous businesses. If product divisions like tools or toys wanted to enlist the services of the IT or human resources departments, they had to write up formal agreements—or use outside contractors. Each unit had to craft its own financial statement, presenting a strategy to Lampert and his committee of top executives. Frank DeSantis, a longtime Sears staffer who now works for a chamber of commerce, remembers feeling a sense of déjà vu. Back in the ’90s, he says, the company briefly tried to reorganize the business in a similar fashion. “The result was confusing to the customer,” he says. “It became disjointed—we started fighting with each other.”

When Sears publicly announced the move on Jan. 22, 2008, shares shot up 12 percent. Inside Hoffman Estates, the mood was chaotic. Six days later, Sears announced that CEO Aylwin Lewis, a former Yum! Brands president, was stepping down. Lampert appointed an operations executive, Bruce Johnson, as interim chief. (He’s now CEO of Sears Hometown and Outlet Stores.) Meanwhile, there were more than 30 slots to fill at the head of each unit. Executives jostled for the roles, each eager to run his or her own multibillion-dollar business. Marketing directors interviewed with the newly appointed presidents, hoping to snag coveted chief marketing jobs. “I worried about the structure—that it would end up breaking apart into people only thinking about themselves,” recalls Bill Stewart, former chief marketing officer for Kmart, now vice president of marketing at solar company Sunrun. The new model was called SOAR, for Sears Holdings Organization, Actions, and Responsibilities. Sears employees would later give it a different name: SORE.

As the company rolled out the plan, Sears executives held dozens of meetings to decide how units would interact. By 2009 there were around 40 separate divisions, according to an internal company document. Lampert expected SOAR to help Sears attract a higher caliber of talent. But it also created a top-heavy cost structure, according to a former vice president for human resources. Because Sears had to hire and promote dozens of chief financial officers and chief marketing officers, personnel expenses shot up. Meanwhile, many business unit leaders underpaid middle managers to trim costs.

The most cumbersome aspect of the new structure, former employees say, was Lampert’s edict that each unit create its own board of directors. Because there were so many departments, some presidents sat on as many as five or six boards, which met once a month. Top executives were constantly mired in meetings.

Under the new model, Lampert evaluated the different divisions—and calculated executives’ bonuses—using a metric called business operating profit, or BOP. As some employees had feared, individual business units started to focus solely on their own profitability and stopped caring about the welfare of the company as a whole. According to several former executives, the apparel division cut back on labor to save money, knowing that floor salesmen in other departments would inevitably pick up the slack. Turf wars sprang up over store displays. No one was willing to make sacrifices in pricing to boost store traffic.

In an e-mail, Chris Brathwaite, a Sears spokesman, writes that executives work together if it makes sense. He added: “Clashes for resources are a product of competition and advocacy, things that were sorely lacking before and are lacking in socialist economies.”

At the beginning of 2010, Lampert hired 20-year Wal-Mart Stores veteran Jim Haworth to run Sears and Kmart stores as president of retail services. Haworth, an affable, mustachioed Midwesterner, saw immediately that Kmart’s food and drugs were more expensive than those at Walmart and Target. So he met with a few top executives, including Chief Financial Officer Mike Collins and operations chief Scott Freidheim, to look into discounting goods such as milk and soda.

That summer the group asked the company’s internal research team to study the idea, according to eight former executives. The researchers came back with a proposal: Cut prices at several dozen Kmarts across the country, bringing the cost of items to within 5 percent of Walmart’s. The business unit presidents agreed. But when Haworth’s group tried to get them to cough up $2 million to fund the project, no one was willing to sacrifice business operating profits to increase traffic.

Eventually the team brought the idea to Johnson, the CEO, and asked for a loan to fund it. The idea was rejected. Freidheim, Collins, and Haworth are no longer with the company.

Former Sears executives say their biggest objection to Lampert’s model is that it discourages cooperation. “Organizations need a holistic strategy,” says Erik Rosenstrauch, former head of Sears’s DieHard unit, who is now CEO of Fuel Partnerships, a retail marketing agency. As the business unit leaders pursued individual profits, rivalries broke out. Former executives say they began to bring laptops with screen protectors to meetings so their colleagues couldn’t see what they were doing.

Appliance maker Kenmore is a widely recognized brand sold exclusively at Sears. Under SOAR, the appliances unit had to pay fees to the Kenmore unit. Because the appliances unit could make more money selling devices manufactured by outside brands, such as LG Electronics, it began giving Kenmore’s rivals more prominent placement in stores. A similar problem arose when Craftsman, Sears’s beloved tool brand, considered selling a tool with a battery made by DieHard, also owned by Sears. Craftsman didn’t want to pay extra royalties to DieHard, so the idea was quashed.

Although Sears does not dispute these examples, the company maintains that the SOAR model compels the divisions to engage in fruitful collaborations. Instead of showing up for unproductive meetings, Lampert writes, “they participate in activities and relationships only if they believe it can help their business unit.”

The bloodiest battles took place in the marketing meetings, where different units sent their CMOs to fight for space in the weekly circular. These sessions would often degenerate into screaming matches. Marketing chiefs would argue to the point of exhaustion. The result, former executives say, was a “Frankenstein” circular with incoherent product combinations (think screwdrivers being advertised next to lingerie).

Eventually Lampert’s advisory committee instituted a bidding system, forcing the units to pay for space in the circular. This eliminated some of the infighting but created a new problem: The wealthier business units, such as appliances, could purchase more space. Two former business unit heads recall how, for the 2011 Mother’s Day circular, the sporting-goods unit purchased space on the cover for a product called a Doodle Bug minibike, popular with young boys.

Disputes between business units should rise to the attention of Lampert and his top officials, says Bill Crowley, an ex-ESL executive who served as Sears’s CFO. “The structure was designed to allow for conflicts to be dealt with, discussed, resolved, and, if necessary, adjudicated,” he says. Other former executives say this often doesn’t happen, largely because business unit heads are intimidated by Lampert.

In the weeks leading up to Black Friday in 2011, Sears discovered that some of its rivals planned to open on Thanksgiving at midnight. Sears executives knew they should open early, too, but couldn’t get all the business unit heads on board, according to former executives. (A Sears spokesman says the decision “was not contingent on the business unit structure.”) Instead, the stores opened early the following morning. One former vice president drove to the mall that night and watched families pack into rival stores. By the time Sears opened, he says, cars were leaving the parking lot.

A month later, Sears announced that its performance during the holidays was poor and it was closing more than 100 stores.

As Sears’s sales declined, its business units found themselves fighting over a shrinking pile of money. Last year less than 1 percent of Sears’s revenue went to capital expenditures, much less than most retailers; even thrifty Walmart invested 2.8 percent of its sales. Lampert and his hedge fund own 55 percent of the company. He defends his decision not to invest in the stores by arguing that Sears’s money is best spent elsewhere—such as the online business unit, which he’s showered with resources.

Many retailers, such as Walmart, have segregated online divisions. But the divide at Sears was exacerbated by SOAR. “There are two big differences with online,” says Mika Kasumov, who worked as a senior analyst on the digital side and left Sears to work for EBay. “One, there’s a lot of attention from Eddie. Two, you have a lot of money to spend.”

Former executives say the Sears chief shops almost exclusively online. In recent months he has focused on turning Shop Your Way, the company’s massive loyalty program, into a social network. Lampert says in an e-mail, “As a thinker and investor, I like thinking about what can be not just what was and is.”

Although Sears rarely gets credit, it was an early mover on the technological front. “They’re ahead of most retailers,” says Gary Balter, an analyst at Credit Suisse. “In a way, it’s frustrating.” The company was experimenting with same-day delivery—a service initially called K-concierge, then renamed MyGofer—in 2006. When the company unveiled a MyGofer store format in Joliet, Ill., a warehouse where customers could drive through and pick up goods they had ordered online, the venture was largely mocked. Today, many retailers are experimenting with ship-to-store and pop-up concepts.

And yet former executives in Sears’s digital group say that while some of Lampert’s suggestions were forward-thinking, he barraged the department with quixotic demands. Lampert constantly cooked up ideas: BlackBerry apps, netbooks in stores, and a massive multiplayer game for employees. He ordered the IT department to build a proprietary social network, called Pebble, which he joined anonymously under the pseudonym “Eli Wexler.” (An Eli refers to someone who attended Yale.) Lampert’s intention, former colleagues say, was noble: He wanted to engage with employees and find out what was happening across the company.

It quickly became clear that Eli Wexler was a little too engaged on Pebble. He left critical comments on other people’s posts, according to more than 20 former employees; he even got into arguments with store associates. Word got around that Wexler was Lampert. Bosses started tracking how often employees were “Pebbling.” One former business head says her group organized Pebble conversations about miscellaneous topics just to appear they were active users. Another group held “Pebblejam” sessions to create the illusion they were using the network.

Tight deadlines for the online unit led to errors. A couple of years ago, Lampert wanted to get iPads into the hands of salespeople who could use them to look up information for customers. When the mobile team went into the field to research the idea, they found that store associates thought it might interfere with the sales process.

The team wanted to run a market test to see how the idea played out in real life but were told they had to rush the iPads out before the holidays. Lampert writes that the company tries to “do things quickly and adjust,” noting that companies such as Amazon.com and Facebook “launch products that are good enough, but not perfect, and then rely on feedback to make them better.” The rollout, former staffers say, was a disaster. Salespeople didn’t want to use the devices, which they feared would deter customers. Eventually, says one former executive, store managers told their associates to put the iPads away.

On May 1, several hundred people gathered at Sears’s headquarters for its annual shareholders meeting. It was Lampert’s debut as CEO. As Maroon 5’s song Moves Like Jagger blared, Lampert strode on stage in a dark, slim-cut suit. He trumpeted the company’s double-digit growth in online sales and described a new feature on Sears’s mobile app, Member Assist, that customers could use to send messages to store associates. “We’re going to bring the online capabilities that we’ve built over the last several years into the stores,” he said.

Afterward, shareholders queued behind a microphone to ask questions. An elderly woman from Texas in a beret told Lampert that she was “so happy” to see him onstage. She still had high hopes for Sears, she said.

“C’mon everybody,” she sang. “Stick with this ship, y’all!” She led the crowd in a call and response, urging them to yell “higher” when she asked where the stock was headed. Lampert smiled. “I do appreciate all of you who have stuck with this ship,” he said.

Three weeks later, Sears reported a first-quarter loss of $279 million. Shares plummeted.

While Sears has heralded its online sales, the company hasn’t disclosed revenue figures. Balter, the Credit Suisse analyst, estimates that e-commerce constitutes at most 3 percent of total sales. Lampert’s focus on Sears’s online transformation, he says, is admirable—but the company makes the bulk of its money elsewhere. Stewart, the former Kmart marketing chief, says: “If you really want to turn those businesses around, you need to drive traffic into the stores. At the end of the day, it’s still a brick-and-mortar business.”

Some retail experts contend that Lampert’s disregard for the stores has hampered digital growth. “Ultimately, your customer is going to make a decision about your brand based on the weakest link. If you have a fabulous website and a crappy in-store experience—or vice versa—that’s going to impact your business,” says Steven Dennis, a former Sears vice president who now runs a consulting firm. “Sears has been good at coming out with a lot of reasonably innovative programs, but … they still don’t answer the question: ‘What’s the overall strategy for the brand?’ ” The truth, former Sears executives say, is no one knows.

When Lampert installed a new merchandising chief, former Brookstone CEO Ron Boire, last year, some saw it as a sign that SOAR was winding down. But executives who’ve left the company in recent months say the model is still in place—and that Boire has lost favor with Lampert. Through Sears spokesman Brathwaite, Boire says he and Lampert have a “strong business partnership.” The merchandising head, who spoke at the annual meeting last year, was notably absent from the stage this May. DePodesta sat in the front row.

While the majority of former Sears executives interviewed characterized SOAR as a failed experiment, several praised Lampert for one thing: his audacity. The retail landscape is littered with the carcasses of failed companies, many helmed by leaders who refused to evolve. Lampert, at least, had an idea. But retail executives with bold visions don’t always survive—just look at J.C. Penney’s Ron Johnson and Barnes & Noble’s William Lynch.

The model does have one distinct benefit: If Sears goes down, its parts may live on. Lampert says in an e-mail that SOAR has made it easier for Sears to divest businesses, such as its outlet stores, and create new ones, like its Shop Your Way division. In his latest earnings call, he boasted that the program’s members now account for some 60 percent of Sears’s sales. Although it’s unclear whether the program is effective—two former Sears executives say the rate at which Shop Your Way members redeem their points for purchases is less than 20 percent, far lower than most loyalty programs—Lampert maintains that Shop Your Way is the future of Sears.

His dream, former colleagues say, is to turn Shop Your Way into a hybrid of Amazon and Facebook. The website now features profile pages for celebrities such as Nicki Minaj and Adam Levine, and Lampert, under his favored pseudonym, Eli Wexler.

While the page is private, members can see Lampert’s wish list, which includes a DVD of The Social Network, a bird-repelling device, and a Sunseeker yacht. He also keeps an extensive shopping list of books. It includes Freakonomics, Super Crunchers: Why Thinking-By-Numbers Is the New Way to Be Smart, and, of course, Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.